The Anxiety of Freedom and Its Transfer to Artificial Intelligence

The individual person, wrote Fyodor Dostoevsky, “is tormented by no greater anxiety than to find quickly someone to whom he can hand over that gift of freedom with which the ill-fated creature is born”.

- The Anxiety of Freedom and Its Transfer to Artificial Intelligence

- The Fear of AI as a Job Killer and Beyond

- The Double-Edged Sword of Automation: From Relief to Overload

- The Culture of Automation: A Shelter or a Trap?

- The Illusion of Outsourcing: The Consumerist Mantra

- The Myth of the Automated Life: A Real Escape?

- The Social and Personal Cost of Automation

- The Influence of Predictive Algorithms on Personal Autonomy

Recalibrating Dostoevsky’s insight, my conjecture is that – in our own time – fear-inducing anxiety of which people wish to rid themselves is increasingly transferred, or more accurately outsourced, to machine-learning algorithms and smart devices.

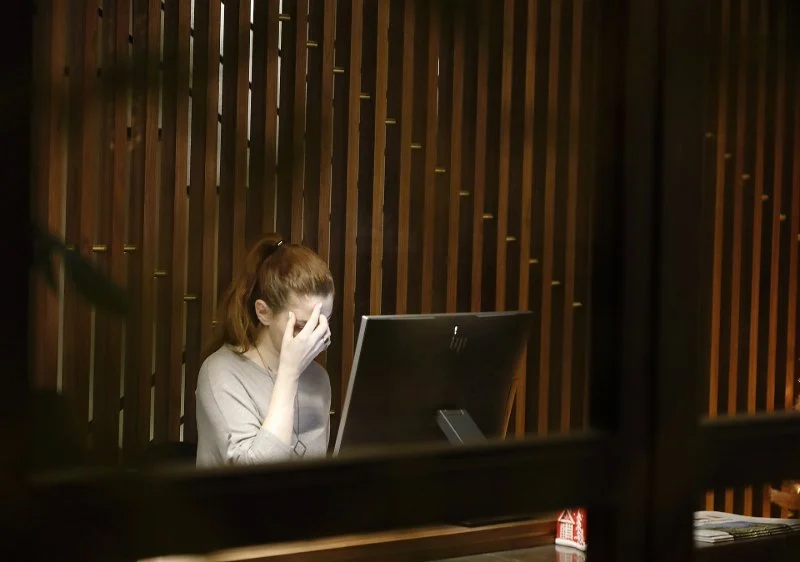

Frustrated and dismayed daily by data overload, the individual increasingly takes flight into the collusive solace of digital automation.

To be sure, most fearsome is the ubiquity of fears encircling automated machine intelligence: it is as if threatening risks and terrifying anxieties may leak out of any nook or cranny of our newly minted technological workplaces and homes, or issue from engagement with our digital devices.

The Fear of AI as a Job Killer and Beyond

Fears that AI is a job killer. Menacing trepidations about digital surveillance and the erosion of privacy. Escalating worries that algorithms accentuate social divisions and stoke racial and gender inequalities. Surging personal vulnerabilities in the face of social media culture.

We live today in a state of chronic overload.

Mind-chafing and body-numbing panic about the militarization of drones and killer robots. Then there is that most terrifying fear that AI jeopardizes not only our workplaces, homes and families but threatens the very existence of humanity itself.

Today the culture of algorithms, apps and automation has reached that stage of evolution where it has become dissolved into the bloodstream of society. One clear instance of this is the ‘double-bind’ of living in a world of information overload.

The advent of digital technologies was, in part, presented as a solution to the problems of coping with our hurried and harried world. Instant decisions and immediate social connections were the promised default mode of an advanced digitalization seeking to counteract our tight enmeshment in professional and personal relations where people were always “time poor”. All that needed to be done could be done through the delegation of personal choice to smart devices.

As it happens, however, there was a price to be paid for this automation ethic. The more that personal agency was outsourced to smart machines and the more that enmeshment in social networks bred ever-expanding connections, the more that people found themselves hassled and overburdened with digital reminders, prompts and never-ending messaging.

The Double-Edged Sword of Automation: From Relief to Overload

Worse than this, the rise of tech in our everyday lives devoured time, both personally and professionally. As if out of nowhere, additional time was now required to research the latest technological gadgets or download new software; ongoing chunks of time were demanded for posting status updates, to say nothing of the endless clicking ‘like’, ‘retweet’, ‘accept’ or ‘delete’.

This is where the seductive power of predictive algorithms comes into the picture, promising to help people cope with the overburdened time demands of this runaway world. Equally importantly, vowing to give people back some control over the future.

More often than not, however, this voyage of automation was revealed as an act of self-effacement, entailing disabling anxiety. For it transpires that the speed of predictive analytics largely leaves people with the feeling that they have been cast adrift.

The Culture of Automation: A Shelter or a Trap?

Frustrated and dismayed daily by data overload, the individual increasingly takes flight into the collusive solace of digital automation. People find a shelter for ‘data fatigue’ in tools like Buffer or HootSuite to automate their social media posts, or Roboform which automatically fills in forms online, or shopping subscription services like Trunk Club, Stitch Fix or Bombfell which automatically purchases clothes selected “just for you”.

Today’s hi-tech culture conditioned by smart algorithms reiterates what each of us absorbs, either by design or default, from our own circumstances and affairs. It presents the world as a series of computational calculations and quantified data, with life-pursuits encoded into machine learning algorithms and marked by the social and technical conditions of outsourcing, offshoring, fragmentation, discontinuity and inconsequentiality.

More and more people feel like they are drowning in emails and texts, overwhelmed by social media posts and consumed by digital to-do lists.

With the arrival of what I have termed “algorithmic modernity”, everyday decisions are routinely outsourced to smart machines and the demands of thinking about decisions vanish, only occasionally requiring further fleeting attention or consent at the click of a mouse.

Problems commanding attention may continually arise but disappear once outsourced to automated machine intelligence, only to be replaced itself by the next cycle of decision-making outsourcing. In this complex entanglement of humans and machines, the limited capacity of individuals to exercise autonomy becomes increasingly frail as algorithms iteratively learn, compose, generate and authorize actions based on the informational attributes of people, data and other algorithms.

The Illusion of Outsourcing: The Consumerist Mantra

Information: we live today in a state of chronic overload. The anxiety-generating and fearsome uncertainty of the age of AI makes the task of managing the scope, storage and retrieval of digitally networked information especially daunting and thus a particularly rich terrain for multiple fears.

In 2023, the world generated in excess of 328 million terabytes of data each and every day. Today’s technologies of speed bring about a derailment of the senses, as people scramble to ‘retrofit’ information into their lives and data updates into their lifestyle activities. More and more people feel like they are drowning in emails and texts, overwhelmed by social media posts and consumed by digital to-do lists.

Forebodings of digital deluge and fantasies of escape feed and reinforce each other.

These digital stresses have a direct impact on the sphere of personal life. But in some parts this plethora of information is also reappropriated by clever advertising stratagems and consumer industries offering market compensation for the vexing dilemma of living a life “pressed for time”. Today’s agonies of information overload require not the limiting of data (although markets promoting digital sabbaths abound) but better systems for organizing data as well as one’s life as a product of data.

The contents of recent top best-selling books provide an indicator of the widespread consumerist vision that one can buy one’s way out of information overload fears on the cheap. The Organized Mind: Thinking Straight in the Age of Information Overload; Algorithms to Live By: The Computer Science of Human Decisions; Overcoming Information Overload; Competing in the Age of AI: Strategy and Leadership when Algorithms and Networks Run the World; Embrace: In Pursuit of Happiness through Artificial Intelligence; and AI by Design: A Plan for Living with Artificial Intelligence.

Collections of ever more instructional, declarative, personalized, fashionable and expensive plans of action aimed at identities under besiegement in the digital age proliferate. Forebodings of digital deluge and fantasies of escape feed and reinforce each other.

In all of this the trick is to shift the burden of managing data from the individual level to that of smart machines. What is advocated here is the outsourcing or offshoring of data to processes of automation. What is desirable is the digitally redistributed life, where data management is outsourced to automated machine intelligence, which re-organizes economic, social, cultural and material relations between people as well as between self and society more broadly.

The belief that you can escape the fears, forebodings and uncertainties of information overload by outsourcing personal decision-making to smart machines is, of course, an illusion. But it is the sort of fantasy which underpins the consumerist mantra that vast advantages accrue to people who live outsourced lives. Perhaps there is a touch of wizardry in the cult of AI-powered task managers, for which the deployment of automated software equals the banishment of annoying repetitive daily tasks.

The Myth of the Automated Life: A Real Escape?

Data management programs that offer in-app automations, such as Hive, HubSpot and Zappia, serve to streamline workflows for recurring everyday tasks. Platforms such as Mailchimp emphasize the self-automation imperative and facilitate new regimes of response to the ongoing tidal wave of daily email messages.

The self-automation ethic is taken a level higher with Google’s Duet AI which, once the ‘take notes for me’ feature is enabled, can summarize and action items during online meetings, provide mid-meeting summaries when people run late on business calls, or go over any details the user might have missed with the assistance of a Google chatbot.

In Algorithms of Anxiety, I argue that people feel increasingly overwhelmed and often persecuted in today’s culture of AI.

The perfection of automated lifestyles has been conceptualized in the likeness of Singularity-style harmony, in which the integration of agency and algorithms is guided by the principle of stability and order. Fear, to be sure, has emerged as a building tool of digital outsourcing used in the fabrication and maintenance of automated lifestyles. This ongoing, relentless outsourcing of tasks to processes of automation is not about the management of data, but about displacing the burden of data management to make room for the inescapable lure of other possibilities and alternative potentials shaping the great digital revolution of our time.

Automated living favours the exhilarating potential and speed of outsourcing; also the lightness and lack of commitments or obligations that outsourcing is hoped to deliver. Automation of daily living allows life to be adapted to an endless exploration of, and endemic experimentation with, digitalization (from social media to ChatGPT to the Metaverse) as people worry about missing important opportunities.

To put it in a nutshell, today’s information overload and accompanying fears of self-immobilization can be outsourced to tomorrow’s automated software for enhanced living. But such an orientation is rooted in the fear of missing out, the frustration that we have been denied possible freedoms. Living in the digital age, besieged by an endless menu of choices, means coping with harrowing fears and alarming uncertainties of perpetually falling short.

The Social and Personal Cost of Automation

More and more, people are deeply troubled by the scale, scope and synergies of Big Tech. They may feel resentment and indignation at the ways in which their personal data is collected, stored and transformed into valuable knowledge across behavioural futures markets where Big Tech and other digital companies profit. They may also be anxious about how the rise of digital platform owners and network service providers result in increasing concentrations of economic, social and political power.

At the same time, however, there is a palpable sense that automated life is here and, by and large, here to stay. People increasingly, perhaps more often than not, live as if the delegation of personal decisions and everyday tasks to artificial agents is the only way in which to cope with this runaway world. Sometimes, perhaps increasingly often, it appears as if there is no ‘outside’ to the smart machines and automated computational models that pervade our lives.

But without question our brave new world of AI changes the dynamics of social life: the delegation of personal decisions to smart machines might often result in new opportunities and benefits, but such delegations can also be a way of narrowing our interests or constraining our desires. So, the pressing question is this: why do people assume that they need to keep automating their lives in order to lead fulfilling lives?

The Influence of Predictive Algorithms on Personal Autonomy

In Algorithms of Anxiety, I argue that people feel increasingly overwhelmed and often persecuted in today’s culture of AI because, thanks to the rise of emerging technologies, they spend much of their time being told by predictive algorithms what it is that they supposedly really want.

It is, to be sure, extremely challenging now to get a sense of what it is the one might want in life given the sway of predictive analytics. The weighted predictions and calculated probabilities of algorithms serve increasingly as substitutes for individual agency and rein in the capacity of people for autonomous action in the world. In the face of information overload, the promises of predictive analytics for displacing the fear-inducing mentalities of doubt, uncertainty and ambivalence have been severely culturally inflated.

To convert the whole world into a giant prediction machine may serve as a powerful way of disavowing fear of information overload and the culture of big data, but we urgently need to look at the social and personal costs of this automation ethic and struggle to demonstrate – and make real – the opposite.

Reproduced with permission from Polity Press. All rights reserved.