Although I had been dabbling with the idea for quite some time, I started writing a book on Black women and human rights five years ago.

At the time, I was a racial justice fellow at Harvard University’s Carr Center for Human Rights Policy (now the Carr-Ryan Center for Human Rights) and in the process of finishing up my second book, Until I Am Free: Fannie Lou Hamer’s Enduring Message to America (2021).

My goal in highlighting Black American women is to illuminate how a historically marginalized group effectively made human rights theirs.

A blend of social commentary, biography, and intellectual history, Until I Am Free centers on the life and ideas of civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer. While much of my analysis of Hamer’s life and ideas focused on her political work around voting rights in the United States, I had decided to venture far beyond U.S. borders.

Unveiling Black Women’s Internationalism

As a scholar of Black internationalism, I spend a lot of time thinking about transnational connections, networks, and solidarities as well as cross-cultural exchanges that have long animated Black life and culture.

I knew that I could better understand Hamer’s ideas and experiences if I carefully considered the interplay of local, national, and global developments. This burning desire led me to write a chapter in which I introduced readers to a Fannie Lou Hamer they had likely not encountered in other works before: a global thinker and a human rights activist.

I explained how Hamer’s 1964 trip to Guinea helped to broaden her political vision. She had traveled to Guinea as part of the delegation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), an interracial civil rights group that played a central role in organizing and encouraging Black residents in the U.S. South to register to vote.

With the help and support of American singer, actor, and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte, SNCC arranged a three-week trip to Guinea in September of that year.

During her three-week stay, Hamer and the other members of SNCC met with several Guinean leaders—including President Sékou Touré—who offered a glimpse into the inner workings of the newly independent African nation.

The trip helped to internationalize SNCC, linking the activists to a broader community of Black freedom fighters. Hamer’s exposure to Guinea and her dialogues and exchanges with African leaders helped her develop, more than ever before, a global racial consciousness and an increased desire to pursue transnational networks and solidarities.

When she returned to the United States in October 1964, the trip’s impact was evident—her speeches in the months and years to follow would center on the important links between the history and experiences of African Americans and other people of color abroad. My account of Hamer’s internationalism was one prism through which to address Black women’s engagement in human rights activism during the twentieth century.

As I concluded Until I am Free, I could not shake the lingering feeling that I had a lot more to say about Black women and human rights history. My conversations with faculty and other fellows at the Carr Center impressed upon me the need to write a book that would articulate how Black women in the United States conceptualized human rights and how they worked to advance it over the course of two hundred years. That’s exactly what I set out to do in my latest book, Without Fear: Black Women and the Making of Human Rights.

Centering Black Women in Human Rights History

Without Fear unfolds a sweeping history of the lives and ideas of a cadre of Black women in the United States to explore how, for well over a century, they were at the forefront of the struggle for human rights.

While the term human rights means and has meant different things to different people, the women featured in my book generally understood it to mean divinely inspired protections guaranteed to all people by virtue of their humanity.

To that end, these activists and intellectuals embraced three core elements of human rights philosophy (which historian Lynn Hunt compellingly lays out in Inventing Human Rights): a focus on natural rights (inherent in all humans), universality (applicable everywhere), and equality (the same for all people).

Black women often framed their demands not only as citizenship rights tied to a particular state, but as concerns for human rights that extended well beyond the borders of an individual nation.

For them, the struggle for rights and freedom in the United States has always been inextricable from the struggle of all people to attain the liberties and rights guaranteed to them, regardless of their social status, nationality, or identity.

Much of our understanding of the history of human rights has been shaped through a focus on diplomatic relations, international laws, nation-states, and nongovernmental organizations. Without Fear offers a different perspective, capturing human rights thinking and activism from the ground up, with mostly excluded actors at the center of the narrative. By moving across the local, national, and global, the book depicts the dynamic interplay of these ordinary individuals—often invisible—with the public officials—mostly white and male—who have dominated the discourse on human rights.

Drawing on speeches, writings, archival material, oral histories, historical newspapers and more, my book pulls into focus the life stories and ideas of both historical and contemporary figures, revealing how they pioneered a human rights agenda aimed at dismantling systems of oppression.

Looking at these women raised a host of questions: What does the struggle for human rights look like from the perspective of the marginalized? How did these individuals draw inspiration from the concept of human rights to challenge racism and white supremacy in their communities and beyond? How did Black women in the United States work to advance the universal and inalienable rights for all people at home and abroad?

How did Black women influence—or attempt to influence—the debate over human rights from outside the halls of power? How did they work to ensure that the core ideals of life, liberty, and security would be extended to all?

I answer these critical questions through an exploration of a diverse cast of Black women in the United States—some well-known and others who are still less known.

Kadi Diallo’s Story

One of the women I discuss in Without Fear is Kadi Diallo, the mother of Amadou Diallo. I draw on interviews I conducted with her over the past few years—as well as Kadi’s writings and speeches, archival materials, and newspaper articles—to shed light on her role as a human rights activist in the United States during the 1990s and 2000s. Since I had recently written about Hamer’s trip to Guinea and how it expanded her political vision, I thought a lot about the connections between these two women’s stories.

A diverse constellation of historical actors in various locales, especially in the Global South, has contributed much to our understanding of human rights as an idea and as praxis.

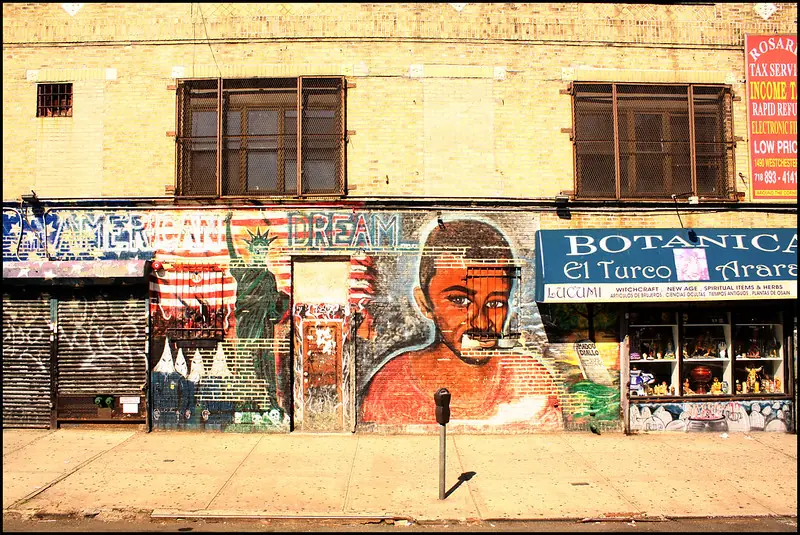

In the case of Kadi Diallo, she was born in Guinea in 1959. Her life would forever change on February 4, 1999, when she received the news that Amadou, her twenty-three-year-old son, had been gunned down by four white police officers—all members of an elite anti-crime unit in New York.

After a long day of work on February 3, Amadou had left his apartment building after midnight. An unmarked police car—with four plainclothes officers—spotted Amadou outside of his apartment building in the Bronx. The police would claim Amadou resembled a rape suspect they were pursuing in the area, although the assaults in question had occurred nine months earlier. When Amadou allegedly reached into his jacket after the officers called out to him, they fatally shot him. At their trial, the officers insisted that they thought Amadou was reaching for a gun.

They would later determine that it was his wallet. The official autopsy revealed that Amadou had been shot at forty-one times. Nineteen bullets had entered his body. Finding out these gruesome details devastated Kadi. And it propelled her to take up the mantle of human rights advocacy.

From Grief to Advocacy

Building on a long line of Black women activists and intellectuals, Kadi Diallo linked local and national struggles to a global fight for human dignity. From her new base in New York City, Kadi worked to raise awareness about Amadou’s case as well as the broader problem of police violence in Black communities.

In May 1999, for example, she appeared before the House Judiciary Committee to testify about her son’s killing and demand “justice and solutions.” She implored members of Congress to pass legislation that would regulate the training and recruitment of police officers.

The women who take center stage in this book labored to redefine the rights and dignity of all people.

A month later, Kadi testified at a series of hearings on police brutality organized by the Congressional Black Caucus. Held at the World Trade Center in New York, they brought Kadi together with Iris Baez and Margarita Rosario, whose sons were also killed by the police, along with Abner Louima—who had been brutally assaulted by officers of the New York City Police Department in 1997.

There, Kadi implored members of the Congressional Black Caucus to “use your power to do what is necessary, so that what happened to me never happens to my son or anybody else’s son.”

In only a matter of months, Kadi became a rising star—a well-respected human rights advocate and an icon in the movement to end police violence. Her public testimonies and grassroots efforts helped to usher in a new era of mass organizing and mobilizing against police violence and racial profiling on a global scale. Writers across the world took notice of the case and drew a similar conclusion: the impunity with which police killed Black people in the United States was a human rights violation. “While the U.S. uses strong-arm tactics in pursuit of ‘world peace,’ it has a difficult time pursuing peace at home,” Australian writer Maya Catsanis argued.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

She went on to highlight the troubling pattern of police violence and discrimination, pointing to the Diallo case as evidence of how the United States failed to safeguard the rights and protections of their own residents, let alone other marginalized groups across the globe. If the United States claimed to recognize the rights of all people based on their humanity, the writer insisted, its leaders needed to do more: “The U.S. must face its internal reality and apply the principle of universal human rights to the people it cherishes most on Earth: its own.”

A Lasting Legacy

In the years to follow, Kadi was involved in several initiatives—including the launch of the Amadou Diallo Foundation—as vehicles for preserving Amadou’s legacy and advocating for human rights for all.

Her story—one of many highlighted in Without Fear—offers snapshots of Black women’s engagement in human rights advocacy in the 1990s and early 2000s from the ground up. Indeed, Kadi’s story mirrored that of countless Black women in the United States whose lives drastically changed following the loss of a loved one to police violence.

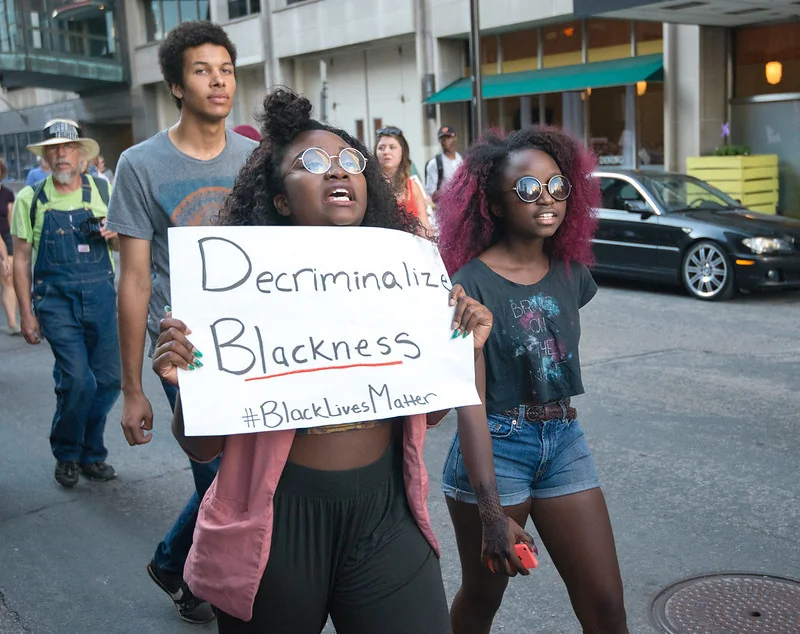

During an era in which the international movement for human rights experienced a significant surge, Black women in the United States found themselves fighting on the grassroots level for the recognition of Black rights and dignity, including protection from police violence.

From the Margins to the Center

Employing multiple tactics and strategies, including community-based activism, mass lobbying, public protest, and international appeal, these women politicized their roles as mothers, daughters, and sisters to call attention to the devaluation of Black lives.

They drew on the diverse demographics and networks in the United States and elsewhere to demand new U.S. laws and policies that would hold police officers accountable for their actions and, in turn, send the message that the lives of Black people everywhere are valuable. Black women’s local organizing and mobilizing during the 1990s and 2000s illuminate how they collaborated to secure human rights on a national and global scale for those marginalized.

Centering Black women in the United States—as I do in Without Fear—is not an effort to place them above others in a comprehensive history of human rights. Indeed, a diverse constellation of historical actors in various locales, especially in the Global South, has contributed much to our understanding of human rights as an idea and as praxis.

My goal in highlighting Black American women is to illuminate how a historically marginalized group effectively made human rights theirs—moving beyond an esoteric concept to an organizing principle that fueled local, national, and global activism. The women who take center stage in this book—some eminent and notable and others who worked in relative obscurity for all their lives—labored to redefine the rights and dignity of all people. And they did so, in the words of African American educator Mary McLeod Bethune, “without fear and hesitancy.”