The Lockstep: Life and Routine at Auburn State Prison

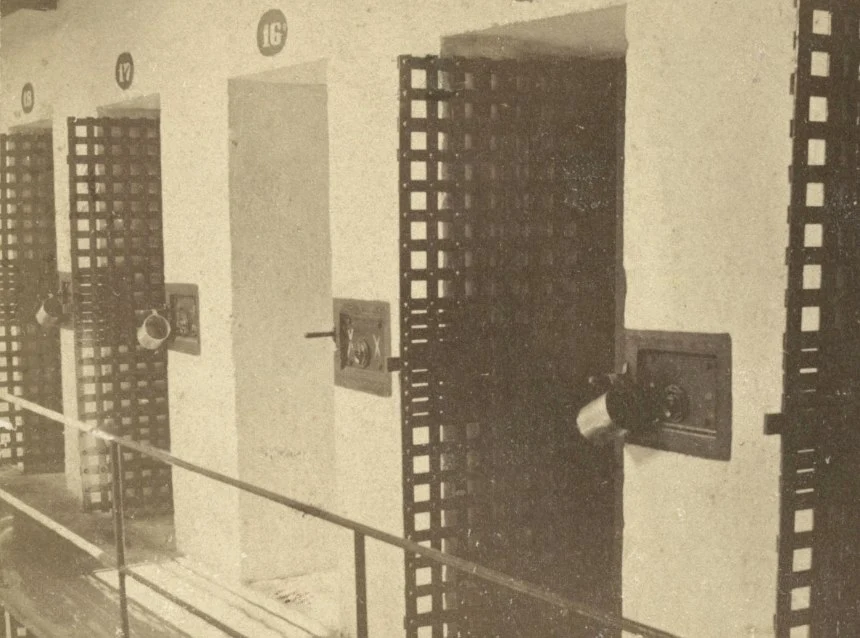

Every morning at 5:30, a bell ordered William Freeman to leave his cell in the Auburn State Prison. Three, four, five dozen prisoners formed a single file on the gallery. Silently, Freeman placed his right hand on the shoulder of the man in front of him and felt the man behind him cup his. Each man’s left hand held a night tub, or chamber pot.

Every face turned toward the guard, heads bowed, eyes sweeping the floor, mouths immobile. They marched—closely, fluidly, appearing, one former prisoner wrote, like “a long reptile crawling out of a dead horse.” This was the “lockstep,” which Elam Lynds and John Cray instituted to prevent communication as prisoners moved to and from factories.

The games had serious underlying functions: not only to lighten the emotional burdens of imprisonment but also to reduce productivity and thereby profits.

But men found cracks of opportunity, and they bored into them. They whispered, passed notes, even taught each other ventriloquism. They learned each other’s names and origins. Some prisoners, particularly African Americans, parodied the lockstep as they performed it, “stamping and gesticulating as if they were engaged in a game of romps.”

Prison Labor: Exploitation and Profit in the Factory System

The men left their cells and marched into the prison yard. They emptied their night tubs into an underground tank, rinsed them with pump water, and set them aside. Then they rejoined the lockstep and marched through factories that produced carpets, clothes, barrels, furniture, and more, with each chamber generating a different racket, a distinct shade of smoke as raw materials began to smolder or boil.

Nearly every day, jailors whipped the prisoners.

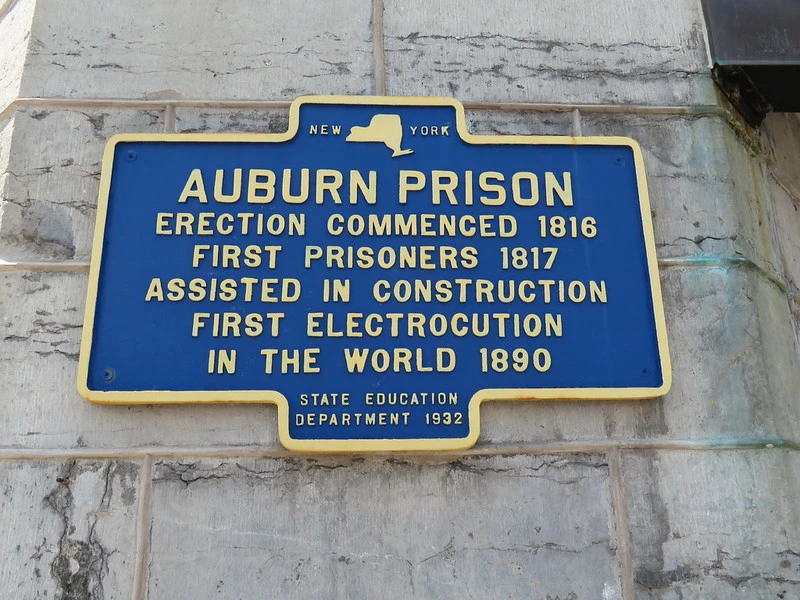

These factories were built into the prison. There, starting in the 1820s, the prisoners were forced to manufacture goods for private companies.

The companies sold these consumer goods throughout New York and beyond. The companies pocketed all the money. Prisoners like William Freeman received no pay.

As men peeled off to assume their workstations, the line of marchers dwindled. The last stop was Freeman’s: the “hame shop.” There, amid gusts of dust, seventy-two men made animal harnesses and hardware for carriages. In 1841, his first full year there, Freeman and others built 6,849 animal harnesses plus hundreds of saddles, stirrups, buckles, carriage lamps, and related items.

Their work was sold wholesale to Cayuga County’s merchants and saddlers at a total market value of almost thirty-two thousand dollars. The contractor bought the year’s labor from the prison for a fifth of that amount—just over seven thousand dollars, less than thirty-five cents per man per day.

Freeman’s job: to file rough iron imported from England, smoothing it in preparation for japanning, a lacquered finish. Alongside nine other filers, he burnished the surfaces of buckles, rings, and other hardware for saddles. It was “coarse work” that required muscle but also “judgment and comparison.”

Freeman filed every morning for two hours, then marched to the mess hall for a half-hour breakfast, marched back, filed more, marched, ate dinner, marched, filed. Every movement regimented, every day the same. Another prisoner described the life: “Each morning, when I seated myself in the shop and cast a look around me upon the things too familiar with my sight, my impression has been accompanied with a sigh, ‘Ah! I am here yet.’”

Freeman resisted through other means: he worked slowly or submitted previously completed work as new.

Sometimes Freeman relieved the tedium by clowning around. Laughter was prohibited, so men made a game of trying to make each other burst. When keepers looked away, Freeman made motions that were so silly the other men in the hame shop could not keep their faces straight—and they reciprocated. Austin Reed, who was incarcerated alongside Freeman, described another Black prisoner who “would come to my bench and pretend that he was showing me something about my work, when at the same time he would be talking about something else which would make me bust out and laugh.”

The games had serious underlying functions: not only to lighten the emotional burdens of imprisonment but also to reduce productivity and thereby profits. If the prison could steal their days’ labor, the men could steal seconds back.

Defiance Through Humor: Acts of Resistance Among Inmates

But resistance incurred penalties. Nearly every day, jailors whipped the prisoners. They whipped them for working poorly or slowly, for “playing old soldier” by handing in the same work on multiple days, for whispering or laughing, for sharing food or pilfering. No disobedience was too small to warrant punishment. Jailors whipped prisoners in the factories, the mess hall, the yard, the cells—but always out of sight of tourists. Jailors whipped prisoners naked, and if they did not strip fast enough, they whipped them more.

They whipped them as they stood; and those who could not stand were clamped into vices or tied by the wrists to rafters, their toes grazing the floor. The strands of the whip, Austin Reed wrote, “sting like the prick of a needle, and when sunken in very deep, the sufferer feels as though he had been bitten by the bite of a dog or been scratch[ed] by the paw of a cat.” Each day, keepers registered these punishments in the state-mandated ledger:

November 2, 1840: “J[ames E.] Tyler Reports the punishment of Allen, nine stripes with the cat for insolence.”

November 5, 1840: “R[obert] D. Cook Reports the punishment of Lynch six stripes with the cat for Spoiling a piece of carpeting.”

On November 1, 1840, barely five weeks into his sentence, Freeman suffered the whip for the first time: “T[homas] H. Toan Reports the punishment of Freeman six strip[e]s with the cat for laughing & making motions to make others laugh.” Humor could sustain a prisoner, but it could also cost him.

At day’s end, the men extinguished the fires in the factories. They marched in lockstep to the prison yard, recovered the night tubs, and pumped some water into each one. They marched to their solitary cells. They slung their hammocks. They slept. The next morning, bells rang. The routine began again.

Resistance and Retribution

Some prisoners may have reduced their labor simply to conserve effort, but Freeman did so within a broader pattern of protest. Repeatedly, he told his supervisors that he “did not want to work” because he “was deriving no benefit” from the labor. He deserved wages, he repeated. He “ought not to work” because had committed no crime. He was innocent, he said, of the horse theft for which he had been convicted.

He “didn’t want to stay there and work for nothing.” He was unyielding, certain in his repeated claims of injustice, quick to talk back to those with power over him. When his verbal arguments were ignored, Freeman resisted through other means: he worked slowly or submitted previously completed work as new.

These protests attracted the attention of Samuel P. Hoskins and James E. Tyler, officers who oversaw the hame shop. Hoskins, “a man of unusual activity and vigor,” once rubbed salt into the wounds of a whipped prisoner. Tyler, who “consider[ed] blacks below whites in intellect” and declared Freeman “below the mediocrity of blacks,” once bound a “crazy” prisoner naked to a post and “cut and lacerated” him “from his head to his heels.” Later, Tyler ordered another officer to wield a glowing-hot iron bar as a weapon against a prisoner, who later died. Prisoners who physically defied Tyler enraged him most.

He once boasted, “I never allow a man to raise his arm at me and live.” Together, Tyler and Hoskins made a routine of kicking Freeman. Tyler would “strike him and kick him generally when he passed him”; and Hoskins kicked Freeman whenever he “got the chance.” The blows were so frequent that Freeman “thought he wouldn’t stand it.” He “made up his mind that he might just as well be dead as alive.”

The Breaking Point

One day, Freeman resisted physically. When Hoskins came at him yet again, Freeman “warded off the blows and weighed out Hoskins one.” Freeman, by his own report, “struck Hoskins with his left hand and faced him around.” Then Freeman “dropped his left hand over his face, and struck him with the right”—a move he called the “butcher’s chop.” Hoskins then ordered other prisoners to hold Freeman down, and the guards “pounded him.” But the beating did not end Freeman’s defiance. To the contrary, it made him resolve “to fight till he died.”

Freeman continued resisting. One day in early 1842, after he had worked in the hame shop about sixteen months, Tyler confronted him for withholding labor and demanded he increase production. Freeman refused. “He told me to go to work,” Freeman said later, “and I wouldn’t.” Yet again contesting the prison’s founding principle, Freeman told Tyler that he “was there wrongfully and ought not to work.” Tyler then ordered Freeman to “take his clothes off ”as preparation for whipping. Next, according to Freeman, Tyler “struck him [and] he struck back.” Tyler told a different story: that Freeman grabbed a knife and lunged at him; “I then had to defend myself.”

Whatever the truth, Tyler was determined to force Freeman “to submit” to the whip. He kicked Freeman, knocked him down, and ordered other prisoners to “clinch” him. Then, instead of the intended whip, Tyler grabbed what was closest: a basswood board measuring four feet long, fourteen inches wide, and half an inch thick. He smashed the board against Freeman’s left temple.

The blow was so severe that the board split lengthwise along the grain, leaving in Tyler’s hands a spike four inches wide. Tyler, who became “excited,” used the remnant of the board to deliver “eight or ten” more blows— “pretty snug,” without recovery time in between. “A black man’s hide is thicker than a white man’s,” Tyler explained later, “and I meant to make him feel the punishment.”

When the board hit his temple, Freeman felt something fall. It was not only his body, knocked to the ground, nerves firing—but also something smaller, inside. He later described the sensation: “It felt as though stones dropp’d down my ears.” Although Freeman did not know it specifically, the blow broke his ear drum, gave him a concussion, and damaged his left temporal bone—the thick bone at the side of the skull that protects the ear’s nerves and other structures. After that—quiet. “The sound went down [my] throat,” he said later. The hame shop became muffled, as if dampened by a heavy curtain. Most of his “hearing was gone, was all knocked off.” It never returned.

To explore further, visit the official publication page here.