Current Suspicions about the Discourse about Religious Liberty

The idea of religious liberty—parsed as the individual’s freedom to believe as they choose or as a restriction on the government’s power to promote one creed or another to the detriment of others—has fallen on hard times of late.

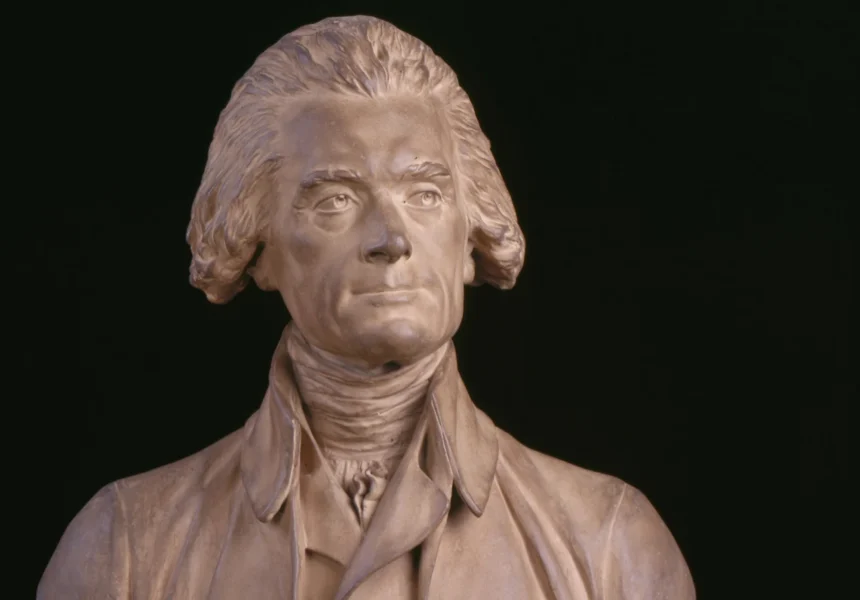

It was once celebrated in the Anglophone world, and especially in the United States, as the genius of Enlightenment philosophes from John Locke to Thomas Jefferson. It is now often decried from both extremes of the political spectrum, left and right. Contemporary American politicians have been notably silent on the topic, even when debates about abortion and immigration suggest its importance.

For intellectual leaders of the political left such as Talal Asad, who drew on the anti-Enlightenment criticisms made by Michel Foucault, religious liberty appeared as a white-Protestant and imperialist conceit. According to this critique, the concept privileged personal belief—especially dear to Protestants—and relegated communal and ritualistic religious practices to the margins. It thereby validated the Enlightenment project of western civilizing at the expense of non-western cultures. It was heavily freighted with racist implications

We need to pay attention to the ways in which both advocates and critics of religious liberty make descriptions of different religious traditions.

Historians of religion in early America followed suit over the past two decades, producing a series of monographs that deconstructed the myth of a religiously free America. David Sehat and Amanda Porterfield, for example, have argued that the language of religious freedom in the federal Constitution and state constitutions of the founding period affirmed the right of a free conscience yet facilitated the proliferation of a Protestant establishment—implicit or explicit—throughout American public life.

For leaders of the political right, the idea of religious liberty has appeared as a secularist ruse to banish Christianity and wholesome morality from western democracies. Critics who have taken this perspective argue for various alternatives. Some conservative Catholics, for example, identify themselves with Catholic Integralism, which holds that states ought to enforce Catholic moral teaching for the common good.

A variety of American Protestants, particularly with charismatic or evangelical sensibilities, explicitly embrace the dictates of Christian Nationalism, as do political leaders in Canada, Hungary, and several non-western states. We can also call to mind Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, who has promoted Hindu Nationalism as a parallel.

Attempts to Reinvigorate the Idea

In response to the marginalization of religious liberty from both the left and right, several American political historians recently have attempted to resuscitate the idea.

The self-contradictions of Enlightenment humanism do not invalidate its central tenets.

Including Steven K. Green, John Ragosta, Thomas Buckley, and Nathan Rives, they return to canonical figures and texts—especially Jefferson and Madison but also early-national New England thinkers—to make two arguments.

These historians contend, first, that such figures promoted the idea through negotiation with political opponents, even if such negotiation set limits and appeared as compromises.

Second, the ways in which Jefferson and his contemporaries idealized religious liberty—as a universal right—legitimates confidence in the Enlightenment understanding of the idea, even with its eighteenth-century constraints.

Attending to Religious Comparison

My recent book, The Opening of the Protestant Mind, suggests that we reconsider religious liberty in different ways than do the political historians mentioned above. It focuses on how popular appropriation of the idea in a Protestant England and America rested on the ways in which non-Protestant religious were perceived.

Attention to the history of religious comparison helps us to see when and how the idea gained traction. Its acceptability depended on opinions about the virtues and vices especially of non-established traditions that lay close at hand to English subjects: radical or separatist Protestantism, Catholicism, Islam, and Indigenous American traditions. Consent to the ideals of religious liberty stemmed in part from shifting descriptions of these religions and the extent to which they were seen as compatible with Britain’s welfare.

This book, then, pays less attention to the Lockean theoretical tradition and more to the mid-level, non-philosophical texts that portray the religious “other” to Protestants in England and New England from 1650 through 1765. These include travel accounts by merchants and military personnel, geographies with ethnographic descriptions, diplomatic letters, dictionaries of the world’s religions, and reports by missionaries. Many versions of these works were frequently reprinted and had a widespread audience.

Restoration-Era Descriptions of Non-Protestant Religions

The central story of this study is change, apparent especially in England’s transition from Restoration to Hanoverian monarchy. England’s first major dictionary of world’s religions, Alexander Ross’s 1653 Pansebeia, was published in the aftermath of England’s civil wars, when political chaos and religious fractures, enhanced by unruly groups who demanded religious liberty, jeopardized the nation.

Protestant missionaries not only changed their description of Indigenous American peoples but also modified their evangelistic practices.

Many post-civil-wars writers—from Ross, through Restoration apologists such as John Ogilby during the 1670s and advocates for England’s overseas expansion such as Nathaniel Crouch during the 1680s—took the position that England needed religious uniformity to overcome political chaos. Only a single religious confession, i.e. established Protestantism, could bring solidarity and security to the kingdom.

As a result, dictionaries and travel accounts described non-Protestant religions (and radical or separatist Protestantism) not only as theologically mistaken but also as politically dangerous: seditious, malevolent, and fraudulent.

Protestant missionaries to Indigenous Americans in New England reflected this view during the 1660s and 1670s, before the outbreak of widespread warfare between English settlers and Indigenous nations in New England. Missionaries such as John Eliot demanded that Algonquian peoples adopt English patterns of life and social organization as a condition for being accepted as Christian. They also expected converts to profess loyalty to the king.

Transformations in Protestant Descriptions of the Religious Other

Political fears of disunity, that is, prompted Anglophone Protestants to reject all other traditions as completely illegitimate. This hardly nurtured the notion of religious liberty: that the state ought to protect liberty of conscience in religious matters and tolerate a variety of religious confessions.

Changes in England’s national politics following the Restoration-era, however, prompted transformations in Protestants’ descriptions of other religions. The so-called Glorious Revolution, or Revolution of 1688, brought to the throne a Dutch prince, William III, who attempted to consolidate support for his regime by, in part, promising religious liberty to those who supported him, including Catholics who recognized his accession to the throne.

In the subsequent decades, during the growth of the British empire and reign of the Hanoverians, the expansion of English commercial networks, including trade with Indigenous peoples in America and with Shia Muslims in the Safavid Empire, further increased English Protestant exposure to other religious traditions and provided motives for cooperation with adherents of those traditions.

The result was a remarkable transformation in the ways that travelers, geographers, dictionary writers, and missionaries represented Catholics, Muslims, and Indigenous Americans. The massive 1742 An Historical Dictionary of All Religions, by Thomas Broughton—influential on both sides of the Atlantic—serves to illustrate.

Broughton did not dismiss non-Protestant religions as illegitimate tout court. He suggested that certain groups or sects within each tradition—Polish Catholicism, for example, or Shia Islam—were admirable because of the social virtues they inculcated: sociability (including toleration of other religions), reasonableness, and social utility or industriousness. Those virtues sustained Britain’s empire and fostered patriotism, and could be evidenced, he and his contemporaries claimed, within various traditions.

Broughton also criticized religious expressions that bred, by his account, vice and social disorder, and especially political absolutism with its intolerance of religious dissent. He scorned the institutionalized Catholicism of the Roman Papacy with its Inquisition, the Sunni Islam of the Ottoman Empire, and Iroquoian, French-allied traditions.

Reflecting this new posture toward the world’s religions, Protestant missionaries not only changed their description of Indigenous American peoples but also modified their evangelistic practices. Believing that their Indigenous interlocutors shared common social values and moral worldviews, they abandoned the mandate to make all people English and, instead, focused their ministries on moral persuasion and consolation.

This is not to argue that eighteenth-century Anglo-American Protestants became ethnographically sophisticated or culturally relativistic but, rather, that they changed their views of other religions and, as a result, began to accept the precepts of religious liberty as a social and political boon rather than burden.

Conclusions

We can draw three conclusions from this study. First, there was no steady perspective on different religions in the popular imagination: neither an unchanging racialized and imperialistic denigration of non-Protestant traditions, nor a steady erosion of Christian belief in the face of secularization. To understand the meaning of religious liberty in the modern Anglophone world, we need to appreciate change through time, which in itself challenges essentialized notions of it as indelibly racist or secularizing.

As a corollary, we do well to pay attention to the political and intellectual contexts for religious liberty and how our understanding is affected by those contexts, especially popular perceptions of our most urgent political needs. We ought especially to focus on the popular appropriation of the idea and therefore on the importance of our descriptions of the world’s religions as essential to our understanding of the idea.

Second, we need to pay attention to the ways in which both advocates and critics of religious liberty make descriptions of different religious traditions. What moral assumptions, what moral discourses, shape our descriptions, and therefore our sense that this or that tradition is either a danger or a potential ally? Much of the criticism of the idea from both the left and the right fails to come to terms with the fundamental moral terms that shape our understanding of—or, in some sense, our ability to tolerate—religious pluralism.

Third, we ought to reinvestigate the Enlightenment-era inheritance and the original appeal of religious liberty—and to come to an appreciation in which the changes represented in that inheritance suggested a way forward even as it was developed out of a peculiarly eighteenth-century English-imperial context.

To put this another way, we ought not to dismiss the idea but recover its possible meanings. Rather than reject it as either a western conceit or a secularizing threat, we ought to rethink the ways in which the notion could serve to bridge cultural differences and shape common identities. As Dipesh Chakrabarty has contended, the self-contradictions of Enlightenment humanism do not invalidate its central tenets. It has the possibility of revealing new forms of sociability, of providing norms of moral discernment, and even of providing us with a measure of much needed self-critique.