The Urban Stage of Modern Consumption

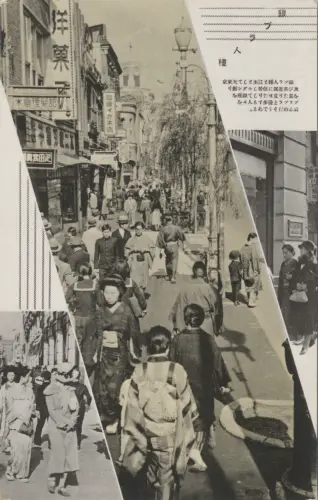

Imagine strolling down one of the main boulevards in Tokyo’s fashionable Ginza district. It is the early Showa period, around 1930. You are engaged in ginbura—the popular activity of sauntering and window-shopping in this high-profile commercial area.

On all sides stand department stores and shops with decorative show windows displaying textiles, clothing, books, and household goods. Advertising signs and banners adorn the streets like an exposition fairground. Then day turns to night, and a flood of electric light and neon signs transforms the street scene into an even more dramatic illuminated theatrical stage.

Bringing into focus a range of design forms, I demonstrate how commercial artists diversified the sensorial impact of advertising campaigns, amplifying their reach and social significance.

A vibrant modern Japanese design movement produced this transformation of the urban environment—what many critics at the time referred to as the “artification” of the streets.

Designing Desire: The Rise of Commercial Art

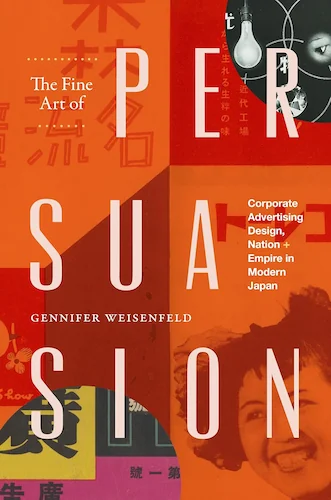

This book tells the story of the birth of commercial art—modern advertising design—in Japan from the turn of the twentieth century through its global efflorescence in the total design event of the 1964 Tokyo Summer Olympic Games.

While the transformation of the city street into a publicity space certainly began much earlier, new technologies in communication, transportation, and mass production expanded and accelerated the production of advertising that bombarded the consumer on an everyday basis.

Japanese advertising designers worked for modern companies to parlay these technological innovations into new forms of publicity for a mass consumer audience.

Public commercial spaces like the Ginza district became modern advertising design’s playground.

At the same time, along with private ventures like the department store, commercial artists also worked in spectacular state-sponsored exhibitionary spaces around the globe, designing domestic and colonial industrial expositions as well as international world’s fairs.

They extended design from the indoor display environment to the outdoor theater of the street, tying together consumer culture and urban space.

By examining the critical cultural role of commercial art as it developed in tandem with mass media and advertising, I map the social relationship between art and commerce in modern Japan.

Without creative design in advertising, brands could not subsist.

I not only demonstrate how integral advertising was to the creation of a national society but also reveal the vast network of design professionals who promoted the brand-name goods that profoundly impacted common perceptions of a modern Japanese lifestyle.

This network extended transnationally from Asia to Europe, the United States, and the Soviet Union. These commercial art specialists were early developers of “corporate identity systems” in Japan. They systematically developed ways to visualize brand and corporate identities that enabled differentiation of consumer products in the market.

Branding the Nation: Aesthetic and Affective Economies

Brand image definition was increasingly important for the success of most major Japanese companies. According to business historian Louisa Rubinfien, Japan’s “commercial world of ordinary household goods had evolved not only from a commodity-to a brand-oriented market, but also from a merchant-to a manufacturer-dominated market.”

This focus of corporate manufacturers on selling brands nationally rather than supplying goods locally led to a heavy reliance on aesthetics to inculcate aspirational desires among the consumer public, even when that public often did not have the financial wherewithal to purchase such goods.

I argue that advertising design’s aesthetic and affective surplus provided substantial added value necessary to compensate for the markedly higher prices of brand-name goods.

Aesthetic surplus was the extra artistic investment in advertising design to convey more than practical information about the product and imbue it with appealing qualities.

Affective surplus conjured emotive layers around commodities that mobilized the consumer’s feelings in connection with the product or company—a precursor of present-day “mood advertising.”

These surpluses provided visual and sensory pleasure, entertainment, and emotional experiences that exceeded the use value of the products they promoted.

The corporate sponsors that I consider here were all consumer-oriented companies that invested considerable capital into advertising and design to establish their brands in the market. It is noteworthy that after more than a century in business, they are all still major companies with well-known national and global brands.

Without creative design in advertising, brands could not subsist. And “if art is the most persuasive of all methods of expression,” as Holbrook Jackson wrote in Commercial Art in 1928, “it may be assumed that the association of the artist with the display of merchandise would increase the persuasiveness of display, and therefore augment that turn-over which is the life-blood of commercial enterprise. Excellence of design and beauty of form are the most persuasive of all things.”

Prominent Japanese toothpaste manufacturer and active design sponsor Lion Dentifrice declared advertising a kind of “fertilizer” for the enhancement of commodities. If we follow this agronomic metaphor, then design is the carefully cultivated flower that attracts the bees and provides nectar to facilitate pollination.

Visual Forms and the Sensorial Language of Advertising

Bringing into focus a range of design forms, I demonstrate how commercial artists diversified the sensorial impact of advertising campaigns, amplifying their reach and social significance.

These include the creative realms of letter design, packaging, postcards, show window displays, and kiosks and other modes of outdoor publicity, as well as the better-known forms of posters and print advertising—all originally embraced under the category of commercial art.

This book seeks to advance the global turn in design history by centering Japan as an active node of production in an international design network and as a real-time participant in a transnational dialogue rather than a latent and passive cultural recipient on the periphery.