Absorption as Framework for Encounter

For over five centuries, Jewish presence in the Americas has come into contact with Black and Indigenous presences in these same spaces. From Canada to Argentina, these groups have coexisted, intermingled, and diverged. In many cases, they have been shown to have “absorbed” one another.

Literature from throughout the Americas has referred to ‘absorption’ to mean co-optation, assimilation, and appropriation in Jewish experiences with racial otherness throughout the Americas.

Convergences among Jewishness, Blackness, and Indigeneity in both the U.S. and in other parts of the Americas shed light on how race is understood.

Encounters between Jewish, Black, and Indigenous inhabitants of various nations throughout the Americas are couched in terms of “absorption” as a way of signaling the vexed relationships characterized by both mixture and separation, acceptance and rejection.

Fictional Representations of Absorption

Guatemalan-American Jewish author Francisco Goldman’s 1992 novel, The Long Night of White Chickens, has its mixed-race Jewish character Flor ask, “Guatemala, in what we like to think of as its deepest self, is Mayan. We, who aren’t actually Indian, what is it we absorb?” (242) This character uses “absorption” to speak of the ways in which Indigenous encounters with Jews throughout the Americas are bound up in particularities of individual and collective connections to the nation.

Where Goldman voiced his character’s concerns about what she and others who “aren’t actually Indian” “absorb” from the Maya, U.S. novelist Philip Roth also focused on absorption through his creation of the fictional “Office of American Absorption” in his 2004 novel, The Plot Against America.

At its core, the novel (and its 2020 adaptation as an HBO miniseries) is a dystopic fantasy whose central conceit is the catastrophic effects of “absorption”—in this case, forced assimilation.

For her part, playwright and actor Anna Deavere Smith has described her verbatim approach to theater in her Ted Talk, “Four American Characters:” “[I] interview people, thinking that if I walked in their words…that I could sort of absorb America. I was also inspired by Walt Whitman, who wanted to absorb America and have it absorb him.”

Smith’s 1992 one-woman “verbatim” play Fires in the Mirror represents Jewish and Black neighbors in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, in the aftermath of the 1991 riots following the death of a Black Guyanese-American child run over by Rabbi Menachem Schneerson’s motorcade. Smith “walks in their words” in an attempt to “absorb America.”

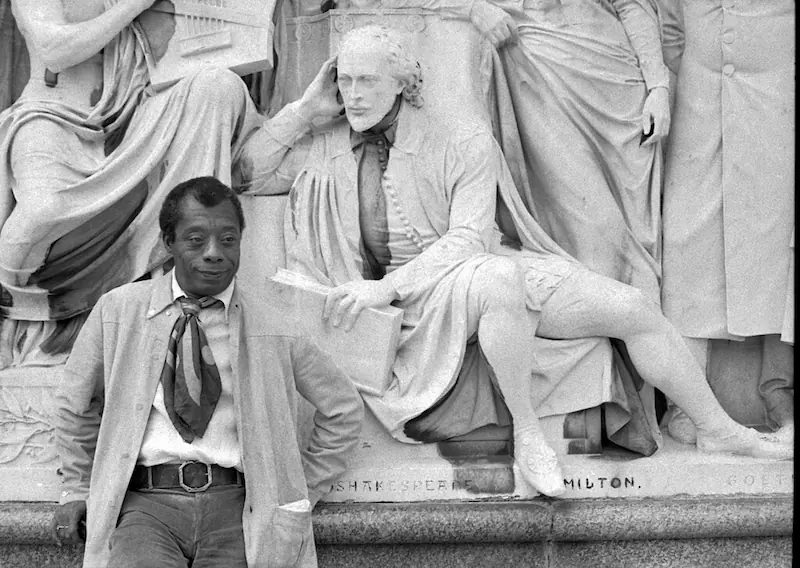

Twenty-five years earlier in New York City, James Baldwin had noted in a 1967 New York Times piece, “it is bitter to watch the Jewish storekeeper locking up his store for the night, and going home. Going, with your money in his pocket, to a clean neighborhood, miles from you, which you will not be allowed to enter.”

Jewishness, Whiteness, and Racial Mobility

In Baldwin’s essay, to be Jewish in the Americas is to benefit from the upward social mobility that allowed the shopkeeper to move out of Harlem, where Black neighbors remained.

For Baldwin, the Jew is absorbed into middle-class white America. The phenomenon that Baldwin observed in 1967 is so because, despite the very real and atrocious oppressions that Jews escaped to come to the Americas, Jewish presence in nations throughout the Americas is a function of settler colonialism and immigration policies in nations that allowed entry to white immigrants.

While, in Harlem in 1967, James Baldwin noted the bitter feeling of watching the Jewish shopkeeper leave for a ritzier neighborhood, a fictional representation of Bom Retiro in Sao Paolo, Brazil, set three years later shows a young Jewish boy remarking that he wants to “be Black and to fly” in Cao Hamburger’s film The Year My Parents Went on Vacation (2006).

Absorption is present in multiple, contradictory ways in Jewish–Black and Jewish–Indigenous encounters in the Americas.

Hamburger conveys a Jewish fascination with Afro-Brazilian identities that verges on appropriation—the absorption of the Afro-Brazilian into the Jewish imaginary. For Baldwin, Jews were afforded the upward social mobility of whiteness by being absorbed into white spaces, while for Hamburger’s young protagonist, Jewish belonging in 1970 in the país de futebol (football country) in Pelé’s heyday involved a desire to be Black.

Jewish fascination with Blackness is present in Hamburger’s film as well as in Philip Roth’s novel The Human Stain, which imagines a Black man who has passed as white and Jewish for most of his adult life. Critic Jennifer Glaser has discussed Roth alongside other Jewish American authors in the context of Jewish racial ventriloquism, a model that she articulates and through which Jewish American authors grappled with their own categorization as white through literary representations of other racial categories.

Paradoxes of Absorption

Absorption is present in multiple, contradictory ways in Jewish–Black and Jewish–Indigenous encounters in the Americas. Often, Jews are absorbed (assimilated) into whiteness while other minority groups do not pass as white. By extension, Jews can become complicit, or absorbed, in settler colonialism and racial capitalism. Jews can “absorb” elements of Indigenous or Black identities—paradoxically, often as a way of attaining and maintaining their status as white.

The etymology of “absorption” explains much of the paradox of how absorption functions: the “ab” signals separation, the “sorb” signals introjection. Absorption involves both separation and joining. The term also evokes ideas of liquidity, perpetuated across generations through the fluidity of racialized memory, and porosity, which is problematized by the very different notions of “mainstream” culture throughout the Americas.

Absorption Narratives’ approach to race and ethnicity destabilizes US-centric critical practices.

Absorption simultaneously problematizes yet maintains ideas about racial purity, which are particularly significant for conversations about Jewishness and race in the Americas given the historical meaning of blood purity used both to fuel anti-Semitic and anti-Muslim policies in fifteenth-century Iberia and as a framework for coetaneous and later ideas about racial mixture in the Spanish colonies.

Absorption also conjures such notions as the “one-drop rule” in the twentieth-century US and Native American blood quantum. In their own ways, both concepts are predicated on the degrees to which the blood of ancestors of different races is or is not absorbed.

Settler Colonialism and the Politics of Inclusion

Indeed, absorption has also been invoked to discuss settler colonialism and Indigenous relationships to mestizaje (broadly defined as racial mixture) in the Americas. Both M. Bianet Castellanos and Lorenzo Veracini have noted that both mestizaje and settler colonialism “absorb” Indigenous people into the national body politic. In this way, a focus on the concept of absorption bridges conversation about mestizaje and settler colonialism.

As both Bianet Castellanos and Veracini underscore, absorption is a paradoxical function in which Indigenous groups are paradoxically “incorporated” into the body politic of the nation. To think of Jewish presence in the Americas as a function of settler colonialism resists the “absorption” of difference into the body politic by disaggregating and reconceptualizing the parts that have been absorbed into homogeneous notions of mestizonational identities as a result of unexamined settler colonialism throughout the Americas.

Jewish presence in the Americas is often a function of settler colonialism, even if Jews were arriving to these places seeking refuge from persecution. As historian David S. Koffman has argued, situating Jewish presence in the US and Canada within the framework of settler colonialism moves beyond the celebratory narratives of belonging that often characterize understandings of Jewish life in the Americas, allowing us to think of Jewish complicity in such phenomena as manifest destiny.

Beyond Borders: Rethinking Race Through Narrative

Jewish encounters with Black and Indigenous communities throughout the Americas take place within “contact zones” defined by Mary Louise Pratt as “the space of imperial encounters, the space in which peoples geographically and historically separated come into contact with each other and establish ongoing relations, usually involving conditions of coercion, radical inequality, and intractable conflict.”

These spaces chronicle the convergence and blending of ethnicities and religious practices from different cultures that have long characterized racial and spiritual paradigms in Latin America.

Contact zones are riddled with complexities of convergences that are sometimes simultaneous and, at other times, take place diachronically. Here we may think of neighborhoods that were once predominantly Jewish that have since become predominantly Black or Indigenous as a function of Jewish access to whiteness and to upper social mobility.

Convergences among Jewishness, Blackness, and Indigeneity in both the U.S. and in other parts of the Americas shed light on how race is understood. Absorption Narratives’ approach to race and ethnicity destabilizes US-centric critical practices. In so doing, we come to see that US-focused models for thinking about racial alterity vis-à-vis Jewishness are limiting and that the story of race relations in the Americas must necessarily be told and analyzed as a hemispheric story rather than from US perspectives.

If Francisco Goldman’s Flor asks, “What is it we absorb,” I ask in Absorption Narratives: what is it that we as readers and audience members absorb from fiction that contemplates these points of contact? What do we absorb from stories that eschew these points of contact? If there are any answers to these questions of how Jewishness bears on how race is constructed throughout the Americas, I show that these answers are to be found not within national or regional boundaries, but by reading between the lines and between geographical boundaries.

For it is beyond these borders that we begin to discern the ways in which fiction might be able to unite the seemingly ununitable. These narratives remind us of the necessity to continue grappling with and reimagining the ways in which encounters between individuals and categories have informed and will continue to inform intergroup dynamics as well as self-understanding within the paradigm of centuries of coloniality.