Footprints at the Border

On a trip to the southwestern borderlands a few years ago, a friend and I visited the Mariposa border crossing, near Nogales, Arizona. Wandering through the gardens outside the facility, I was struck by the artwork.

- Footprints at the Border

- Designing the Border as Connection

- A Border Open to Goods, Closed to People

- The Paradox of Bordering a Borderless Power

- Borders as Political and Religious Ensnarement

- Crossing, Coercion, and the Imagination of Absence

- Drawing the Line: Dispossession and the Making of the Border

- Co-opted Sovereignty and the Asymmetries of Power

- Corporate Personhood and the Disappearance of the Border

- Owning the Line: Capital, Cattle, and the Outsourcing of Sovereignty

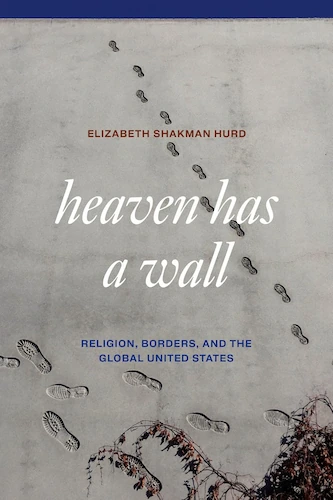

I took the photo that appears on the cover of Heaven Has a Wall, showing adult- and child-sized footprints embedded in bulletproof concrete walls. The footprints suggest a parent and child walking together across the walls and up and out of the facility, with the smaller set veering off into the sky. Had they died? Left the building, or the country? Had they been separated? The walls were eerie, and also, oddly humanizing.

Designing the Border as Connection

Between 2009 and 2014, the Mariposa Land Point of Entry underwent a $250 million renovation led by the engineering firm Stantec. By a stroke of luck, a friend from high school who worked at Stantec connected me with the lead engineer on the renovation, who introduced me to the head designer, Eddie Jones of Jones Studio.

Jones described his vision for Mariposa as a point of connection between the two countries, rather than division. He found inspiration in the poem “Border Lines,” by Arizona Poet Laureate Alberto Ríos, and proudly noted that today the poem is inscribed in a glass partition in the queueing lanes in the lobby of the renovated point of entry:

“Let us turn the map until we see clearly:

The border is what joins us,

Not what separates us.”

When I asked Jones about the footprints, he said that the cold, bullet-proof concrete walls demanded that they “tell a story.” A public artist on his team came up with the idea of covering the tilt-slab concrete in footprints.

They cast the concrete on-site and poured it horizontally in tilt-slab construction. Real sneakers were used to make footprints on the walls. When I asked him where the footprints are meant to be going, he told me simply that, “they’re on a journey.”

A Border Open to Goods, Closed to People

In fact, many more tomatoes pass through Mariposa than people. The crossing is the main entry point for sixty percent of all winter produce consumed in the United States. The total value of exports and imports passing through annually is roughly $35 billion. For tomatoes, the border is open.

This is Mariposa: public art venue, checkpoint, trade hub, art exhibition, tomato point of entry, welcoming oasis, and bulletproof security structure. Borders and borderless-ness. Poetry and prison. Gardens and guards. Welcome and walls. Fountains and fear. This signaled something about US borders that needed attention: the American desire to both have and to transcend borders, to enforce and suspend the law. To be first among equals.

To make the rules but not be subject to them. Americans can build the Panama Canal, bring democracy to the Middle East, conquer outer space, innovate out of climate catastrophe, revise the rules of international order, and make border crossing as pleasant as a trip to an art museum with a fountain and garden.

In the words of the authors of the 9/11 Report, “the American homeland is the planet.”

The Paradox of Bordering a Borderless Power

Studying US borders reinforced this paradoxical sense of limitless confinement. Borders are elusive. They’re more complex than they appear at first glance. They are liminal zones, places of extremes, exceptions and special rules. It is tempting to look over your shoulder after you cross.

The border is a site of retrenchment and transcendence. Enforcement and erasure. The suspension of the law and its prosecution. The US ferociously defends its borders even as the ideal of America remains borderless.

This impulse persists through history into the present: the Louisiana Purchase; the annexation of Texas and expansion into California; debates over annexing Cuba, and today, Greenland, the Panama Canal, Venezuela. What holds it all together?

US borders always have been present and absent, avowed and deferred. Heaven Has a Wall climbs inside this paradox and explores its contours and contradictions. Each chapter takes on a different aspect of US bordering: creating, enforcing, suspending, and refusing.

These alternate with a series of interludes that immerse the reader in border-related puzzles: Where is the US base at Guantanamo? In the US, Cuba, both, or neither? What’s it like to be a pilgrim forbidden from traversing a state border when the pilgrimage is older than the border itself? What happens when states attempt to transform rivers that naturally meander into fixed national boundaries?

Borders as Political and Religious Ensnarement

Borders also draw a person into something bigger. Like politics. And religion. In her book Consuming Religion, religion scholar Katie Lofton observes that, “religion isn’t only something you join, open-hearted and confessing. It is not only something you inherit… [It] is also the thing into which you become ensnared despite yourself.” It “enshrines certain commitments stronger than almost any other acts of social participation.”

Borders are also sites of enchantment and mystery.

Borders are like that. They are modes of social participation that enshrine strong commitments. They compel you to participate. They ensnare you. You don’t get to choose which side you’re born on. The agent holds your passport.

Sometimes they literally hold your passport. One of the interludes is about my own experience crossing the border at O’Hare, the main airport in Chicago, with my family. I was being interviewed by an agent who had just returned from the US-Mexico border in Texas.

After chatting for a bit, he asked me what I did for a living, and I told him I was studying US borders. His posture turned aggressive. He said that media reports about detained children in cages “were all lies.” This conversation took place a few days after DHS had released a damning report documenting horrific conditions for children held in cages near the border, including in Texas. I was at a loss for words.

Crossing, Coercion, and the Imagination of Absence

This interlude, and the book as a whole, invite readers to think about crossing—their own crossings, those of their friends and family, and those of others.

Who goes to interrogation, prison or detention, and who doesn’t need to show a passport? How are these encounters changing with biometrics and facial recognition? I invite readers to consider the extent to which borders are concrete, embodied, and often terrifying. There is an element of the Inquisition in crossing them. The border agent and the medieval inquisitor are not as far apart as one might assume.

US border tactics have gone global.

Borders are also sites of enchantment and mystery. They attract counter-sovereigns and protest movements. They invite other experiences of temporality. They encourage us to contemplate other possibilities for the organization of time, space, and authority. Ironically, the border’s weighty presence incites us to imagine the possibility of its absence. Or at least reconfiguration.

One of the interludes in the book illustrates how the border can be both present and absent simultaneously. It is a “gilded age” story of possession and dispossession, of land grabs that unite cattle herds and separate families, of economic and political power. Of ranchers and railroads, on one side, and dislocation and dispossession on the other.

Drawing the Line: Dispossession and the Making of the Border

US control of what is now the US-Mexico borderlands began in the mid-19th century with the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the 1853 Gadsden Purchase.

The border sliced O’odham lands down the middle, leaving families on both sides. The line-drawers did not consult the tribes, and most were unaware that a border had been drawn, and remained so for decades. Later in the 19th century US border enforcement intensified as the US sought to expand into areas that had been informally self-governing. This is the era of railroads, mines, and manifest destiny. In 1916 President Wilson established a permanent reservation for the O’odham and erected the first US-Mexico border fence.

For the O’odham people, the late 19th and early 20th centuries were a time of dispossession. Historian Rachel St. John notes that although “some (Tohono O’odham) took jobs as cowboys with Mexican and American ranching outfits and became integrated as wage earners into the lower rungs of the transborder economy, the broad picture was one of land loss.” Diminished to one-tenth of its original size, today their reservation spans 2.7 million acres—roughly the size of Connecticut—the second-largest reservation in the US.

Co-opted Sovereignty and the Asymmetries of Power

Today the O’odham share a substantially diminished and partially co-opted exercise of sovereignty with the US government. In 1974, Congress created an all-Native Border Patrol called the Shadow Wolves, assigned to the Homeland Security Investigations tactical patrol unit in the O’odham Nation.

Native peoples, including the Yaquis and O’odham, were hit hardest as US-owned Mexican “corporations” became the linchpins in a thriving emergent transborder capitalist economy.

Celebrated as among the most effective units in Border Patrol, the Shadow Wolves have trained border guards, customs officials, and police in far-flung Central Asian and Eastern European countries including Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan. US border tactics have gone global. The O’odham have mixed feelings about cooperating with US authorities. Many continue to protest the environmental, social and spiritual costs of the militarization of their communities.

On the other side of the equation, also in the mid to late-19th century, US ranchers were buying up huge tracts of land on both sides of the US-Mexico border. Their experience was different from the Native communities. At the same time as the border was being enforced at the expense of the O’odham and other Indigenous nations, it was being circumvented by wealthy capitalists seeking to invest in the Mexican side of a booming transborder capitalist economy. Americans had long been prohibited from owning land near the border by a Mexican restricted zone law. But investors circumvented the law to make the border disappear, as if by magic.

Corporate Personhood and the Disappearance of the Border

The trick was to invoke corporate nationality and become legal corporations under Mexican law. This allowed the investors “to access all the economic advantages of Mexican citizenship without giving up their identity and status as individual U.S. citizens.” As St. John explains, “under Mexican law, any company incorporated under the laws of Mexico carried all the rights of citizenship, save voting. By forming a Mexican corporation, American capitalists legally transcended the limitations of U.S. citizenship.”

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

They overrode US sovereignty, even as they enacted their own forms of “mini-sovereignty” over their ranches. When it came to business interests across the line, as far as these investors were concerned the US was borderless. Corporate entities owned by Americans and incorporated under Mexican law were Mexican corporate nationals. The legal fiction of corporate personhood united with the impulse of American expansionism and the license of transnational capital to overwrite assertions of territorial sovereignty by both the Mexican state and the O’odham Nation.

Among those taking advantage of Mexican corporate nationality was “Texas John” Slaughter, a cattleman and “wild west” sheriff who arrived in Arizona in the late 1870s. Slaughter served two terms as sheriff of Cochise County, during which he helped track and capture the famed military leader and medicine man from the Bedonkohe band of the Ndendahe Apache people, popularly known as Geronimo.

Owning the Line: Capital, Cattle, and the Outsourcing of Sovereignty

In 1884 Slaughter purchased the San Bernardino Ranch, a 65,000-acre property spanning the Arizona-Sonora boundary. The 1853 Gadsden Treaty had drawn the international boundary through the ranch, leaving one-third in Arizona and two-thirds in Sonora. Slaughter set up his headquarters on the line. Not only did his cattle graze back and forth across the line, but the ranch became a way station for cattle purchased from Sonoran ranchers and sold to American consumers.

The US and Mexican governments facilitated the transition to private landownership by wealthy settlers like Slaughter. In effect, they outsourced their sovereignty. The result was the appropriation of millions of acres of land that were inhabited, used or claimed by Indians and other borderlands people. Native peoples, including the Yaquis and O’odham, were hit hardest as US-owned Mexican “corporations” became the linchpins in a thriving emergent transborder capitalist economy. By 1910, US investors dominated mining, ranching, irrigation, and real estate speculation. Incredibly, at this time Americans owned most of the land on both sides of the US-Mexico border.

Meanwhile, the O’odham were encountering a newly established, and newly emboldened, Border Patrol, led by none other than Texas John Slaughter’s former Cochise County Sheriff’s Office employee, Jim Milton. In accordance with official US policy, Milton adamantly refused to acknowledge tribal rights to cross the border. His former boss, however, could not only cross the border, but own it.

I learned recently that in the late 1950s Disney made Texas John’s story into a Disney TV series, with Tom Tryon as Texas John. The opening theme song goes: “Texas John Slaughter made ’em do what they oughta, ‘cuz if they didn’t, they died.” The narrator who introduces the first episode observes that, “this Old West that we talk about is not so old after all. It’s only yesterday in this young country of ours.”