Architecture as a Target of War and Oppression

Architecture has been a site of struggle at times of wars, occupation, dictatorship, and violence. From Gaza and Mosul to Aleppo and Kharkiv, the destruction of architecture has been used as a tool to cause suffering on local communities, to displace them, and rewrite their history.

Around the world, entire neighbourhoods have been wiped out to make cities and villages uninhabitable for targeted groups. The voices of victims, however, often remain silenced and muted, as their suffering remains invisible and forgotten. We should never let the world normalize destruction.

Preserving Memory and Humanity through Writing

In my book, Domicide: Architecture, War and the Destruction of Home in Syria, I have challenged the current studies and reports on war and architecture, which, in many cases, focus on stones but not the lives of people. I therefore wanted to write a zoomed-in history; a history of the people who lost their homes or have had their lives impacted by forced displacement. I utilize the concept domicide; domus is the Latin word for home, and domicide refers to the deliberate destruction of home – the killing of it.

What we are witnessing in the wars raging around the world is that people’s homes have been deliberately targeted.

When I started researching this book, Syria had been fading away from the news. It has turned from the news headlines into a footnote in history. Since 2011, when the revolution started in March as part of the Arab Spring, over half of the Syrian population has been displaced from their homes (over 12 million people). Even before the full invasion that Ukraine has suffered from by Russia’s forces since 2022, and the outbreak of Covid-19, the world seems to have moved on. Today, people talk of ‘war fatigue’ even when Ukraine is mentioned.

Writing, for me, has become an act of resistance to the erasure of memory; a homage to the people who lost their lives and to those who remain living in extreme conditions within Syria or scattered around the world. Instead of relying only on international reports and news articles, which have turned the suffering and misery in Syria into numbers (e.g., numbers of refugees or destroyed buildings), I started interviewing residents of Syria in their exile. These individual stories provide powerful testimonies to the horrors of war that humanize the suffering of people, instead of neglecting their stories.

It is hard to believe that human beings have the capacity to destroy each other.

One of these stories included in the book, for instance, is the testimony of Hanan, a Syrian-Palestinian architect based in Berlin. Hanan lived in the Palestinian Yarmouk Camp in Damascus before she moved to Germany. She wrote:

I hold home with me wherever I go; the news, the thoughts and the memories are a part of my daily life… I had to see the pictures once, twice and repeat to understand that this is the place I used to live, that under the rubble is what I still, up until this moment, call home… It was all gone in the photos I saw later, the bright, well-lit rooms were eaten by the fire. The only things that I recognized were the remains of the fridge and the bench of the dining table.

I invited the BBC’c chief international correspondent, Lyse Doucet, to write the foreword of my book. My email was sent to her in February 20, 2022, and her reply came from the Ukrainian capital Kyiv. In July the same year, she wrote in the foreword:

Wars of our time, sometimes fought in our name, are not in the trenches; they’re fought street-to-street, house to house, one home after another. Why does a hospital, a kindergarten, always seem to be hit in every outbreak or hostilities? After nearly four decades of reporting on conflict, I now often say: civilians are not close to the front lines; they are the frontline.

Civilians are the frontline. What we are witnessing in the wars raging around the world is that people’s homes have been deliberately targeted. Balakrishnan Rajagopal, an associate professor of law and development at MIT, and the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing, has noted that,

It is necessary to address hostilities being carried out in the knowledge that they will systematically destroy and damage civilian housing and infrastructure, rendering an entire city – such as Gaza City – uninhabitable for civilians.

Rajagopal’s writing has been essential in bringing the destruction of architecture closer to law, as he has been calling for recognizing domicide as an international war crime.

Syria in Exile

The book is structured around different themes. It starts by introducing the impact of urban violence on cities at the time of ‘peace’ (Chapter 1), such as urban inequalities, sectarian segregation, and neglect of cultural heritage sites. Then it moves towards researching the impact of war on Homs after 2011, as millions of people around the country are searching for shelter inside Syria (Chapter 2).

The book further unpacks how the war has been represented in art, culture, and literature (Chapter 3), and then it deconstructs the word “reconstruction” and shows how more waves of destruction and forced eviction might emerge with new destructive reconstruction plans (Chapter 4). The final part of the book reflects on the different ways to resist domicide, including the role of solidarity spaces and the power of preserving memory as an act of radical hope. As Rebecca Solnit puts it:

Your opponents would love you to believe that it’s hopeless, that you have no power, that there’s no reason to act, that you can’t win. Hope is a gift you don’t have to surrender, a power you don’t have to throw away.

As cities wait for their reconstruction to come, it is essential to centralize processes of peacebuilding and justice.

One particular example of the themes explored in the book is the way in which Syrian communities, their allies, and friends have preserved the memory of Syria even from outside Syria. I have, therefore, followed the important writings of Prof. Nasser Rabbat, who co-organized a symposium in 2019 on ‘Reconstruction as Violence: The Case of Aleppo’ (soon to be published as a co-edited book), Al Hakam Shaar, a researcher at The Aleppo Project who has written extensively on his beloved city Aleppo, Houda Fansa Jawadi, who created an urban show titled ‘The City Talks’, and Sawsan Abou Zainedin, who has written on the weaponization of the built environment in Syria.

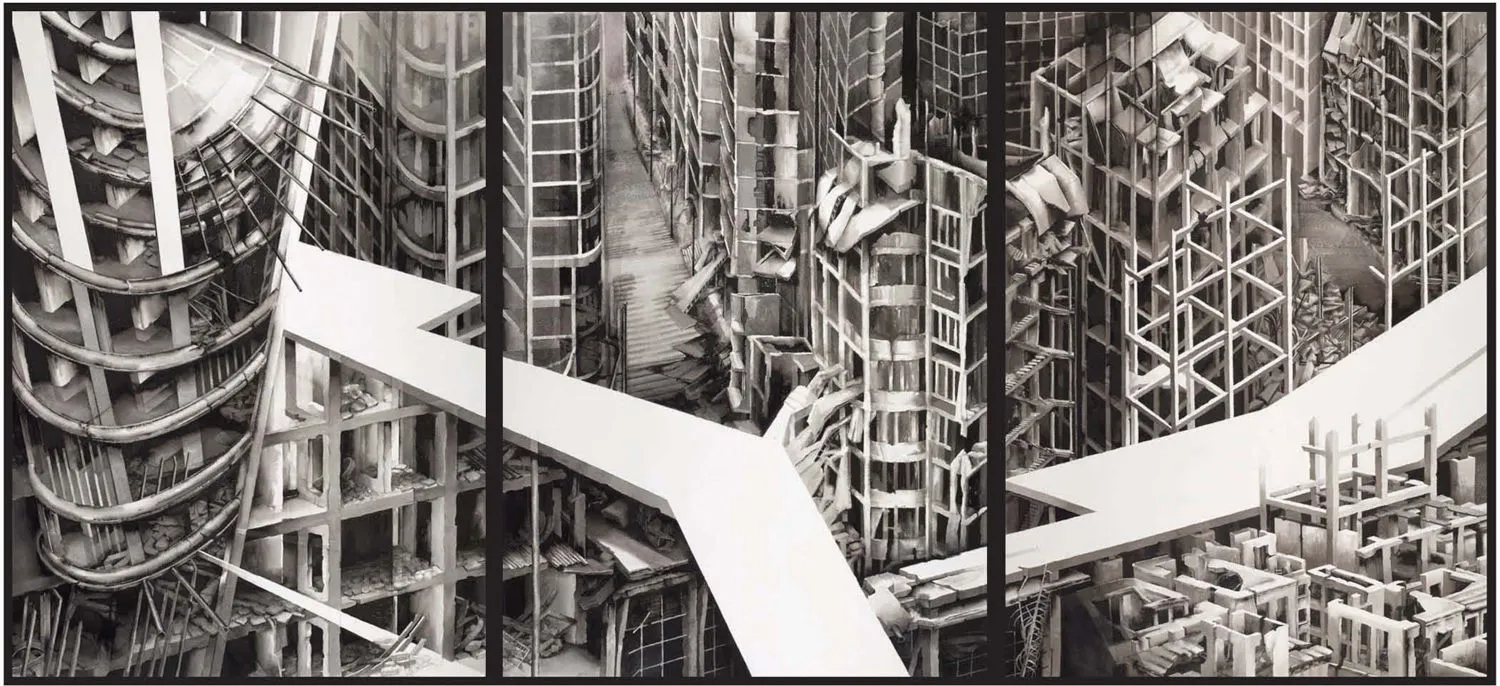

But in addition to Syrian colleagues, friends and allies from all around the world have responded to the war. One of the striking examples is the drawing by artist Deanna Petherbridge, who drew The Destruction of the City of Homs at the age of 79. I included her drawing as the cover of my book Domicide. Deanna passed away in January this year. In an interview with the artist in 2019, she told me:

I feel the most terrible outrage that people can eat a meal in front of the television and watch the destruction of a city and be unmoved by it… I can’t watch the destruction of environments anywhere without having some attempt to understand what it means to people to lose their livelihoods, to lose their families, their identities.

Waiting for Reconstruction Yet to Come

It is hard to believe that human beings have the capacity to destroy each other, to invent so many different ways to kill their fellow human beings and destroy their architecture. In Syria, around half a million people have been killed. But even after all this pain, there has been no transitional justice nor peace.

As cities wait for their reconstruction to come, it is essential to centralize processes of peacebuilding and justice. Reconstruction should not be the rebuilding of the stones only, but the recovery of the millions of broken lives and shattered families. I hope that we arrive at a time where people come together to rebuild every ruined city, every ruined village, where people can live in dignity, justice, freedom, and health.