Foundations of Arctic Cooperation

Arctic Exceptionalism: Cooperation in a Contested World is an examination of the collaborative foundations of Arctic diplomacy and security that have for centuries aligned the interests of the Arctic states, Indigenous peoples, and nonstate actors at the top of the world, even during periods of regional and global conflict and upheavals to the international order.

- Foundations of Arctic Cooperation

- Nationalism and Shifts in Arctic Dynamics

- Indigenous Stakeholders and Their Role

- Challenges to Arctic Inclusivity

- Nationalism and State Rivalry in the Arctic

- Historical Foundations of Arctic Cooperation

- Collaborative Governance and the Arctic Council

- Realism and Pragmatism in Arctic International Relations

- Historical Conflicts and Arctic Stability

- Grounding Arctic Exceptionalism in Realism and History

- The Durability of Arctic Collaboration Amid Crisis

These foundations are being tested by the rise of new Arctic stakeholders such as China and other non-Arctic states with emerging economic, military, and diplomatic interests in the region as it opens up to increasing maritime commerce, resource development, and strategic mobility.

The Arctic, with its remote geography, harsh climate, and historic state weakness, has functioned better as an incubator of cooperation than of conflict.

Beijing, as part of its Polar Silk Road initiative, came under criticism from the United States and US allies for making opaque investments—particularly before Arctic stakeholders had become more familiar with the mechanisms of what came to be described as “debt-trap diplomacy.”

Nationalism and Shifts in Arctic Dynamics

Nationalism and its impact on Arctic diplomacy are intensifying, as became abundantly clear during the 2019 Arctic Council Ministerial meeting in Rovaniemi, Finland, when Secretary of State Mike Pompeo publicly scolded China as an Arctic interloper, creating diplomatic fireworks at the otherwise collegial gathering.

For the first time since its formation in 1996, the council broke with its tradition of producing a consensus statement at the meeting’s end—not for Pompeo’s undiplomatic dustup with China but rather because of the US pivot away from the climate change consensus that had hitherto united all Arctic stakeholders.

The story of Arctic exceptionalism began long before the Arctic Council’s formation a quarter century ago.

In these long months since Russia’s February 2022 invasion of Ukraine, this trend has only accelerated, beginning in March 2022 with the unprecedented boycott of council activities by seven of the eight Arctic Council members under Russia’s second rotating term as council chair, in protest to the invasion.

This pause on Arctic Council activity was remarkable for the unity of the seven boycotting Arctic states, which in the past had experienced their own significant disagreements (primarily between the coastal states abutting the Arctic basin versus the inland and sub-Arctic states).

Notably, five of the boycotting states were NATO members, and the other two, Finland and Sweden, were in the process of joining the alliance (with both now fully accessioned)—which will alter the diplomatic dynamics of the Arctic Council. Some fear it will risk permanently exiling Russia from the council’s circle of consensus.

Indigenous Stakeholders and Their Role

However, the Arctic Council has long prided itself on its collaboration across vast gaps in demography, geography, and economy, with its innovative inclusion of six Indigenous Permanent Participants who enjoy unfettered access to the eight Arctic member states, integrating state and tribal interests in a distinctive and exemplary manner.

Yet the united stance of the seven democratic council member states against fellow member and then council chair Russia came without consultation with the Arctic Council’s Indigenous stakeholders, who were caught by surprise as much by the boycott as by their exclusion from its discussion, a breach therefore of not only the Arctic Council’s interstate harmony but its multilevel state-tribe harmony as well.

Embedded firmly in a realist framework, I present a sober look at the domestic dynamics and components of the Arctic order.

The Permanent Participants have largely given their ex post facto approval of the boycott, with one notable exception being the Russian Association of Indigenous People of the Arctic (RAIPON), which is state controlled at present with much of its former leadership in exile.

The others gave their approval under immense pressure at a time of global consensus against what is perceived as Russia’s naked aggression toward an independent neighboring state. Candid observations by Arctic Athabaskan Council (AAC) chief Bill Erasmus and Inuit Circumpolar Council–Alaska president James Stotts about Indigenous exclusion, as well as the importance of Indigenous engagement to inclusive governance in the Arctic, cannot be overlooked.

Challenges to Arctic Inclusivity

The long track record of inclusivity across the centuries-old East-West fault line and the millennia-old tribe-state fault line is at great risk. Many fear it will not recover and that the Arctic’s long cooperative tradition known as Arctic exceptionalism will be forever altered. But as this book chronicles, the roots of Arctic exceptionalism are deep and have endured numerous tests and challenges before.

The Arctic is not entirely immune from the power-political pathologies of international relations, or completely insulated from their ravages.

The many complex governing and administrative structures—constitutional rights, legislative mandates, and judicial decisions—that have emerged in the modern Arctic, and their alignment with policies and principles embraced by the member state and Indigenous stakeholders on the Arctic Council, have helped to enshrine Arctic exceptionalism.

This has established Arctic exceptionalism not as a normative aspiration but as an enduring dimension of Arctic international relations. It survived not only the bipolar global conflict of the Cold War but also post–Cold War efforts to protect and restore the fragile Arctic environment and post-thaw efforts to combat the unprecedented threats of climate change to the stability of the Arctic system.

Nationalism and State Rivalry in the Arctic

How the intensification of state rivalry and renewed nationalism in the Arctic are affecting Arctic exceptionalism, and they in turn are affected by it, will be the focus of this book.

Rooted in history and international relations (IR) theory, readers will see how realism in a world of anarchy is systemically impacted by the region’s unique extremes, fostering alignments of interests among a diverse coalition of states, Indigenous peoples, and organizations who jointly govern the region and share a common experience of seeking order and survival in the remote, harsh, and ever-challenging Arctic.

This was as true during World War II and the alignment of the Western Allies with Stalin’s Russia as it was during more peaceful times. The Arctic, with its remote geography, harsh climate, and historic state weakness, has functioned better as an incubator of cooperation than of conflict. In today’s contested world, with Europe aflame, it can and should continue to do so.

Historical Foundations of Arctic Cooperation

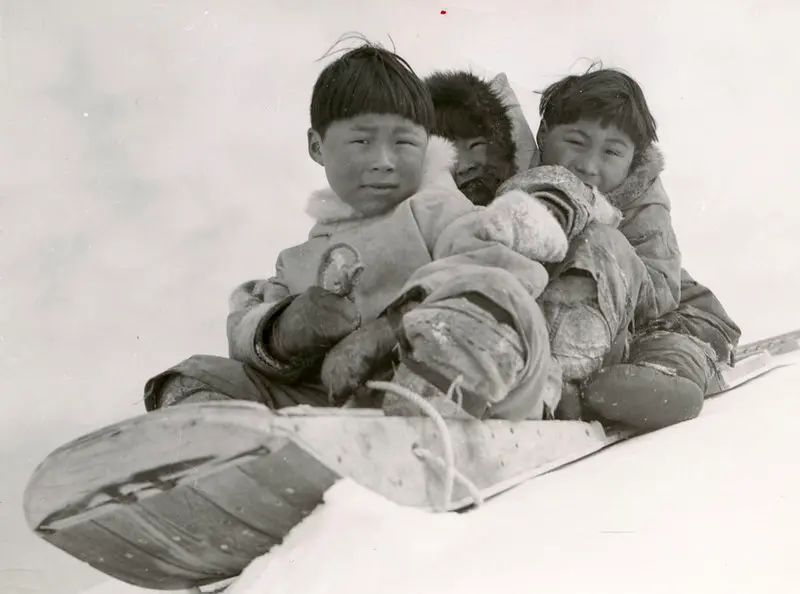

Indeed, the story of Arctic exceptionalism began long before the Arctic Council’s formation a quarter century ago. I trace the roots of the region’s continued, underlying commitment to consensus back to the centuries-long experience of collaboratively managing Arctic lands and resources between tribal peoples and the states that would come to assert sovereignty over their homelands.

First the chartered companies of the colonial-era fur trade, with minimal numbers of settlers, integrated the vast subarctic and much of the Arctic region into the global political economy—leaving Indigenous polities largely intact (relative to other colonized regions). Then, as the newly formed modern states that now govern the Arctic expanded north in the nineteenth century, they by and large adopted this collaborative approach of asserting sovereignty by partnership with native proxies.

This resulted in today’s complex Arctic institutional environment defined by a patchwork of co-management systems enshrined by treaty, legislation, and constitutional mandate. The seeds were planted for an enduring, multigenerational commitment to work together despite obvious asymmetries in power, wealth, and demography.

Collaborative Governance and the Arctic Council

This collaborative governing framework took international diplomatic form with the creation of the Arctic Council; the same players who learned to work together on domestic issues extended their cooperation into the international realm.

New interests are managed largely by welcoming observer technical expertise into Arctic Council working groups while limiting their formal decision-making influence, which carries forth the spirit of collaboration from earlier eras. What defines this book, and my research on the Arctic, is this synthesis of deep history with IR theory.

Thus we do not start with contemporary structures but rather come to understand their emergence over time, and we see in the collaborative sentiment expressed by so many Arctic stakeholders of great variety (large, small, weak, and strong states; stateless tribal peoples; cross-border Indigenous nations; multinational corporations and newly empowered native corporations, among others) not an idealist aspiration but rather the pragmatism born of realism, a balancing of interests amid anarchical pressures that are enhanced by geographical extremes.

Realism and Pragmatism in Arctic International Relations

So, when we look to today’s diplomatic and strategic challenges, we see each rival state leveraging the perception of an intensifying Arctic race for domestic audiences and stakeholders, even though the region in fact has remained relatively stable.

Its borders were mutually respected as the Great Game played out largely in headlines, a staged show to maximize budgets and modernize infrastructure, not unlike the earlier balance of power era when small wars were waged, and alliances rebalanced to prevent a recurrence of great war.

While I accept and defend the premise of Arctic exceptionalism, I recontextualize it here for the real world of geopolitics and military conflict and find persuasive evidence for its continuation amid recent challenges and tensions. Embedded firmly in a realist framework, I present a sober look at the domestic dynamics and components of the Arctic order, each seeking to maximize its own gains, and how these competing interests align at the top of the world to establish a peaceful and stable region in an otherwise anarchic world where peace is in every stakeholder’s interest and war itself is, on a large scale, a logistical impossibility.

Historical Conflicts and Arctic Stability

Historic hot wars in the Arctic, such as the Japanese lightning conquest of the outer Aleutians, and earlier the Confederacy’s final naval assault upon Yankee commerce in the Arctic Ocean in the summer of 1865, and before that the Battle of Hudson’s Bay that brought the Seven Years’ War into the Arctic region with the bombardment of the Hudson’s Bay Company post at York Factory, were intense but brief battles that were part of wider conflicts whose centers of gravity lay far from the region and had modest local impacts at most.

The Arctic, for a variety of reasons that will be explored in the book in detail, is inhospitable to many of the realist pillars of world order, including war, and this contributes to the region’s tendency toward cooperative outcomes. But the Arctic is not entirely immune from the power-political pathologies of international relations, or completely insulated from their ravages.

Grounding Arctic Exceptionalism in Realism and History

This argument is important as it grounds Arctic exceptionalism in both realism and history. Much of the literature on Arctic IR overstates the emergence of a new Arctic cold war or great game and the competitive dynamics of Arctic international relations, overlooking the remarkable capacity of the region to resist the perils of international anarchy and its divisiveness.

Its distinct geopolitics, born of isolation, remoteness, and cold, may be transitioning from what Mackinder called “Lenaland” into a more Spykmanian “Rimland,” but this transition is not instant, nor does it completely offset the region’s underlying harshness.

Because of the Arctic’s unique political geography, the regional and domestic forces that shape Arctic diplomacy remain intact, even as new Arctic stakeholders arise on the world stage. Lacking their own territory, these emerging stakeholders (including rising imperial powers like China and long-declined imperial powers like Japan) are really just interlopers who may increasingly pass through and interact with the Arctic states and their structures, but they will always remain subordinate to the Arctic states and their empowered Indigenous peoples who jointly govern the region.

The Durability of Arctic Collaboration Amid Crisis

All eight Arctic states, including Russia, have shown a remarkably durable commitment to collaboration, even as regional crises erupted around the world, up until the present collapse in circumpolar unity precipitated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Indeed, should Russia and its fellow Arctic states go to war—whether in the Baltics, Scandinavia, or the high North Atlantic—as a result of a collapse in international order, the Arctic will face a challenge unseen since World War II.

Today’s crisis thus threatens Arctic exceptionalism itself. Though not necessarily likely, scenarios of interstate war in the Arctic are no longer viewed to be entirely implausible, and these will be considered in the pages ahead, as will other “internal” scenarios of disruption to the Arctic system including the potential for a secessionary cascade starting with Greenland and expanding across the Inuit homeland of Arctic North America.