- Cinema Beyond Representation: Rethinking Histories and Politics

- The Epistemic Potential of Visual Art: A Short History

- Montage, Inquiry, and the World: Cinema as a Mode of Knowledge Production

- Cinema, Emotions, and the Scales of Justice

- The Limits of Montage and the Urgency of Cinema as Inquiry

- Coda: Decolonial Digging as Habit

Cinema Beyond Representation: Rethinking Histories and Politics

For many viewers, cinema is a form of paid entertainment to relax or escape. In academic circles, cinema is mainly defined as a means of communication, representation, or an aesthetic object, focusing on the director, the stars, or mise-en-scene.

Yet, in contrast to these approaches, I propose another possibility: that cinema, as science, is a mode of inquiry capable of producing knowledge—with significant consequences.

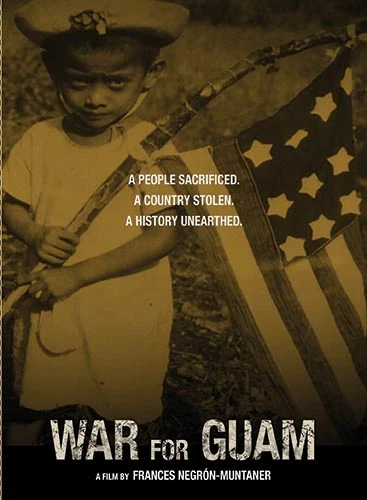

For me, the seed for this idea had roots in frustration. In 2011, I was working on the documentary War for Guam (2014), aired on over 500 U.S. public television stations. The film features rarely seen archival images, contemporary vérité footage, and survivor testimonies.

It narrates how most Chamorros, the Indigenous people of Guam, remained loyal to the United States under a brutal Japanese occupation during World War II, only to endure further loss when the U.S. Navy seized much of their ancestral land upon reoccupying the island.

The challenge was as follows: scholarly consensus posited that Chamorros did not resist naval political control until the 1970s, a period of mass movements in the United States. However, the new ways we related archival and other materials, especially given the relative lack of images or documents explicitly depicting Indigenous resistance, suggested that Chamorro contestation began much earlier, from the moment the Navy touched land on Guam in June 1898.

Recognizing that justice requires politics, artists aim to create knowledge that explicitly challenges dominant power relations.

As a result, we arrived at a different conclusion than most historians. While the Chamorro struggle of the 1970s had connections to the U.S. Civil Rights Movement and other political mobilizations, it was not an offshoot. Chamorro political history was autonomous and distinct. This knowledge allowed for a more nuanced understanding of how these earlier struggles informed present ones, opening new possibilities for contemporary Chamorro politics and cinema.

The Epistemic Potential of Visual Art: A Short History

The notion of “cinema as inquiry” is not new, even if its history, implications, and contemporary relevance are mainly invisible. Scholars and artists have theorized and practiced cinema and the visual arts as a mode of inquiry for at least two centuries. Consider the work of photographer Eadweard J. Muybridge (1830-1904), who deployed moving images to fill in gaps in knowledge about “animal locomotion.” In a series of photographs taken in 1877, he “froze” each phase of a horse’s movement to demonstrate that all four galloping horse’s hooves leave the ground simultaneously.

During the twentieth century, visual artists moved away from Muybridge’s positivist perspective yet continued to theorize about the capacity of art to produce new knowledge about the self and world. A notable example is Pablo Picasso’s well-known Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), a painting that most of his contemporaries condemned as “mad or monstrous” and that critics often describe as a “transition” between realist and cubist styles.

Building on the work of artists such as Paul Gauguin, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Henri Matisse, as well as Iberian and African aesthetics, Picasso interrogated the relationships between form, light, and color. Moreover, although some of his conclusions remain politically contested, Picasso inquired into broader questions.

These included the limits of European realist representation, the ability of a two-dimensional medium to represent three-dimensional movement, the impact of women’s growing autonomy, and the increased presence of African migrants, objects, and knowledge for European hegemony, particularly that of men. Picasso himself was explicit about his work’s goal and method: “I never do a painting like a work of art. It is always research.”

Montage, Inquiry, and the World: Cinema as a Mode of Knowledge Production

Picasso’s claim is consistent with how filmmakers have conceptualized cinema as a mode of inquiry for over a century. In the 1920s, director Sergei Eisenstein named filmmakers “researchers” and defined “montage” or editing as a practice beyond adding one shot to another. Instead, he conceptualized montage as a general artistic method across many art forms, which is best equipped to address the “juxtaposition of two facts, two phenomena, two objects,” and “activate” spectators to see from the director’s point of view.

Building on Eisenstein, in the 1960s, French director Jean-Luc Godard argued that montage does more than relate objects or communicate the director’s intentions to the audience. For Godard, montage is a method to achieve at least two core goals.

- The first is to “discover the hidden connection between two things – images, ideas, words – that no one else has seen before.”

- The second is to reveal the ties between “the subject to the world, [and] of the subject to others.”

Most recently, artist and theorist Trinh T. Min-ha suggested that cinema as research encompasses more aspects than cinematic or image montage. It must also include the invisible labor of cultivating an audience, which is often more challenging for women and people of color. In Min-ha’s terms, “Film itself is a form of research, albeit a research in every single step taken with filmmaking and building audiences: writing, shooting, editing,” and more. Accordingly, cinematic montage is a form of “assembly,” relating objects, images, machines, and bodies in time and space.

Cinema, Emotions, and the Scales of Justice

If art is seen as a form of research capable of producing knowledge and building new relationships among people and communities, it prompts the no less central question of “To what ends?” Artists and theorists generally concur that the arts can “move” people. For instance, influential art education theorist Elliot Eisner argued that the main task of art is to evoke emotion, which can foster the necessary “empathy that makes action possible” personally and collectively.

However, for many practitioners, facilitating empathy is not enough. Recognizing that justice requires politics, artists aim to create knowledge that explicitly challenges dominant power relations. In Godard’s terms: “There’s a shot before, and another one after…. We see a rich person and a poor person and there’s a rapprochement, and we say: it’s not fair. Justice comes from rapprochement. And afterward, weighing it on the scales. The very idea of montage is the scales of justice.”

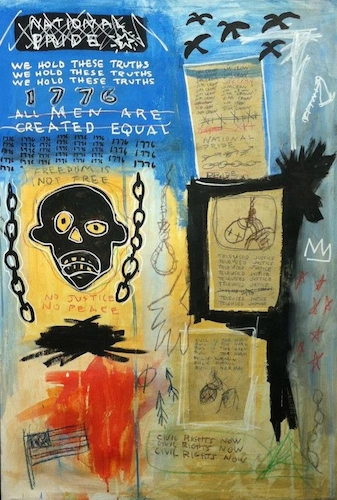

A compelling example of how montage invites viewers to collaborate in producing knowledge with the purpose of justice is the art of Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1987).

Primarily practicing montage in two-dimensional space, Basquiat created a dense archive employing collage, repetition, improvisation, copying, and experiments with color. This novel archive reinterpreted and recontextualized Black, Caribbean, and Indigenous memories and forms of knowledge to challenge colonial epistemologies and visualize justice.

Basquiat’s practice is evident in the painting Created Equal (1984). In this work, he depicts the head of a Black man framed by chains and positioned beneath the phrase “WE HOLD THESE TRUTHS,” written three times. Basquiat follows this with “1776” and the crossed-over phrase “ALL MEN ARE CREATED EQUAL.”

Both refer to the first line of the U.S. Constitution, which, despite stating that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” excluded enslaved Africans who were legally considered property and continued to inflict harm on their descendants after emancipation. Through this montage, Basquiat prompts readers/viewers to consider alternative associations and disrupt knowledge that has become so naturalized that it is perceived as “empirical truths.”

The Limits of Montage and the Urgency of Cinema as Inquiry

The broad notion of arts as inquiry is then not just the juxtaposition of seemingly unrelated images. It’s a more complex process that enables spectators to reconceptualize the relationship between ideas and images, particularly those that, as filmmaker Raoul Peck stated, have been “silenced.” Montage, therefore, serves as an archive of past collective struggles and thwarted possibilities. It also generates new knowledge by inventing forms, activating memory, and creating or restoring the links between people and places deleted, destroyed, or distorted by dominant narratives congealed in monuments, museums, and other visual forms.

A story can be truthful only if it offers insight through selectivity and specificity.

Yet, while the visual arts can, through montage in space (visual artists) and montage in time (filmmakers), reveal, connect, and reframe, they have limits: not everything can be created, found, or linked.

Furthermore, the necessity of associating pieces inherently suggests a loss that may remain unrecognized or unaddressed. As film theorist Jacques Aumont points out, “Considered coldly […] editing is nothing more than the reiterated production of these visual and mental traumas, showing us events severed from their causes and consequences.”

Additionally, montage can only show what can be made visible. However, not everyone can access image-making knowledge and technologies like video, photography, and painting. Even when such resources are available, the dominant legal, media, and academic institutions that distribute, discuss, and preserve artistic practice often favor particular perspectives, geographies, and forms over others.

Moreover, since most films and visual texts tell stories, inquiry can entail symbolic and political violence. While stories can provide insight into some forms of justice and truth, they can also obscure or suppress others. This highlights a fundamental narrative paradox: a story can be truthful only if it offers insight through selectivity and specificity. Consequently, the knowledge or truth produced by cinema is provisional and subject to debate.

Still, the concept of cinema, and more broadly, art as inquiry, may be more urgent now than ever. It enables us to recognize that not everything is visible; what we do see has been selectively represented, and much has been omitted. Furthermore, at a time when a small number of institutions control cinema, the sheer volume and fragmentation of images make it increasingly difficult to establish connections or links between them.

Coda: Decolonial Digging as Habit

In other terms, the concept of cinema as inquiry serves as a reminder of what I refer to as “decolonial digging,” or the practice of continuously investigating and challenging coloniality and its effects. While for Godard, digging signifies a permanent disposition of curiosity, decolonial digging is more akin to how Afro-Puerto Rican historian and theorist Arturo Alfonso Schomburg used the term in his classic essay, “The Negro Digs Up His Past” (1925). In this text, Schomburg relates the knowledge of Black history to expanding present possibilities.

A rich illustration of this concept is Patricio Guzmán’s Nostalgia for the Light (2010). In this film, Guzmán tells the parallel stories of astronomers researching the history of the universe and Chilean women who, armed with small shovels, search the vast expanse of the Atacama Desert for the remains of their loved ones who were murdered by the Chilean military during the Pinochet dictatorship from 1973 to 1990. The film highlights how prevailing power structures have suppressed buried knowledge, from concealing the existence of specific individuals or communities to obscuring abuses of power.

Ultimately, approaching cinema as inquiry requires a commitment to digging, making connections, and engaging in ways we can neither understand entirely nor master. Like all political and artistic practices, cinema is always unfinished and involves imperfect attempts where filmmakers cannot help but fail. Yet, sometimes, we fail beautifully, if only for a moment, and that alone is worth sharing.

This article is an abridged version of “Cinema as Inquiry: On Art, Knowledge, and Justice,” first published in 2023.