“Gentrification is Genocide”: The Fight Against Urban Displacement

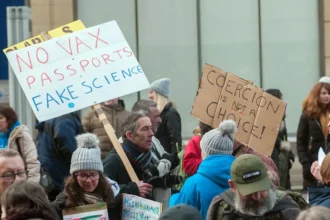

Housing activists have been using the slogan “gentrification is genocide” to speak to the violence that the processes of gentrification cause. For housing activists, gentrification leads to the removal and displacement of marginalized populations, breaking and killing, both literally and figuratively, the social and community ties that folks have built, and many times, they are not able to return to those places because they have been destroyed.

To some, such a statement seems to inflate or dramatize a process that does not need to be labeled with such language. Still, to the people displaced and the activists fighting for their communities, gentrification is just part of a long set of tools used to exploit and destroy communities. Activists use the slogan to address the slow and violent process of gentrification, not something that happens at a single moment, but something that takes time to develop, perpetually displaces people, stops them from maintaining and creating community ties, what I call “the generational killing of the social”: Gensociocide.

It is the White middle-class ethos, regardless of the racialization of the body enacting it, that alter and change neighborhoods.

To use the term genocide, in this sociopolitical moment, might seem like a stretch or something that might not seem to carry the total weight of what the word entails. In some way, critiques against the usage of the word are correct because the definition of genocide does not directly include displacements or evictions, but this is a limitation, not a strength.

However, many activists, particularly Indigenous folks, would greatly benefit from the adaptation of the process of gentrification being incorporated into the definition of genocide because it would allow them to make a case for settlers taking over their lands, resources, and livelihoods. To address this important cause and that of marginalized populations, I suggest using gensociocide.

Redefining Genocide: Gentrification as a Tool of Settler Colonialism

As I argue in White Supremacy and Racism in Progressive America: Race, Place and Space, gentrification is invested in gensociocide.

In the book, I make the connection that gentrification is connected to settler colonial practices that aim to perpetually extract resources, repurpose land, uphold exclusive White communities/ethos, maintain racist and gendered structural inequality, and invest in the creation of exclusive White futures.

Gentrification is the process of replacing one group with another of a higher socioeconomic class.

I claim that gentrification is an active and settler colonial process that utilizes the same principles and maintains an imperialist-white-supremacist-capitalist-patriarchal structure.

I show in the book that settler colonialism can be made visible in the city by just reframing our lenses, as it is part of the fabric of places and spaces that have been taken over by settler colonialism.

The book frames whiteness and white supremacy as a spectrum that supports the false idea that White folks, their bodies and ways of being, are naturally superior.

Whiteness and white supremacy are not just about White people, as non-White people also support those same structures, but White folks ultimately reap all the benefits.

In many gentrified places, it is not just White folks that replace marginalized populations but middle and upper-middle class non-White folks that maintain a White middle-class ethos, lifestyle, and aesthetics. It is the White middle-class ethos, regardless of the racialization of the body enacting it, that alter and change neighborhoods.

The production of the Gentry

The term gentrification was coined by Ruth Glass in 1969 to speak about the emplacement of a middle- and upper-class group of people replacing those of a lower socioeconomic class or racial and ethnic minoritized groups. In short, gentrification is the process of replacing one group with another of a higher socioeconomic class.

What was particularly important, and often seems to be ignored, is that she named racialized and minoritized groups, e.g., a West Indian population, being replaced by a middle and upper-middle-class gentry (those of good social position). In this simple yet illusive statement, the Whiteness and the White-middle-class ethos of the incoming group seems to be ignored or assumed as the norm and was not questioned.

As the term was being developed, Glass aimed to capture not just the displacement of people but the emplacement of those of “good” social position or breeding. As some scholars have argued, gentrification is the process of displacing/emplacing a middle-upper-class ethos and the bodies that support that kind of development. Not all gentrified areas are being taken over by White folks, but the White middle-and upper-class ethos is present.

This ethos/lifestyle/spirit is tied to the embourgeoisement of spaces and places and enmeshed in racialized discourses and ideologies. In particular, the middle- and upper-class ethos is tied to the idea of private property, the family, and the children. In my book, focusing on Jamaica Plain, a borough of Boston, Massachusetts, USA, I interviewed self-identified White progressive folks to outline their housing trajectories and paired that with other qualitative methods.

Many of the interview respondents initially lived in alternative housing arrangements, communes, shared households, and when their White children arrived or began thinking about having them, they resettled into a heteronormative whiteness where private property became the central focus.

The White Ethos: Private Property, Family, and Resource Hoarding

What I uncovered in my book is that the idea or figuration of the White child is a powerful tool used to justify private property claims and different forms of resource hoarding. As one interview respondent stated, “cost, value, family” becomes the logic that connects private property to the White family and child.

By centering the financial cost and investment, one can make sense of the value-driven potential that the White family and children hold as tools for the accruement of equity, and thus, worthy of investment to continue the perpetuation of whiteness. The White family, in particular, the White children, become economic-cultural-political-emotional resources used to continue emplacement and the extraction of resources.

The figuration of the White family and children is used to reference a master narrative, accounts/discourses used to disseminate national ideology, that advances exclusive White futures. In the end, private property, whiteness, and the figurations of the White child and family are what the “gentrification is genocide” slogan aims to highlight.

The Child (mostly read White)

In general, the category or idea of ‘the child’ is not socially questioned and mostly left alone. In popular and political discourse, the idea or figuration of the child is often utilized as a silencing tool or a way to rationalize a particular process. Claudia Castañeda has theorized that the construction, figuration, and image of the child is a site that obscures power dynamics that rationalizes systemic inequality.

A clear example of this is politicians on all sides of the political spectrum that state, “x is for the children” or “we must do x to save our children.” Often times, the cause may not have anything to do with children but the idea and image of the child carries a particular form of power/vulnerability that is hard to engage with or rebuke. In my book, and what “gentrication is genocide” aims to convey is that the process of gentrification is connected and tied to particularly structural and violent processes that ultimately benefit the spectrum of Whiteness.

Gentrification is just another way to make settler colonialism visible in the city.

Interestingly, many of my interview respondents were critical of their Whiteness and the privileges afforded to them, but still used and reaped all the benefits. Some participants stated, “don’t talk to me about race, talk to people of color,” to appear progressive, while others were critical of the role of education and the privileges afforded to White families by mentioning,

“I was listening to… On Being (podcast)[on] like how white parents do this thing like resource hoarding [for their children], you know, and like even diverse integrated schools, like more white families end up taking more AP tests and things like that… Like [they are] pushing for their kids to have all these extra benefits… like people aren’t necessarily advocating for kids of color and things like that.”

In general, even the disavowal of whiteness or being critical of whiteness still allows folks to perpetuate the advancement of White interests. The idea that the White folks should not talk about race and should leave that to be done by people of color is a form of privilege.

This perspective reaffirms that White folks don’t have a race or that they should not speak about race and racism, which ultimately leaves racist structural inequality uninterrupted, while still appearing progressive. Research participants talked knowing about their white privilege, shared facts about racialized inequality, Black Lives Matter movement, and about how White parents hoard resources at the expense of students of color, but still participated in those exact same processes to provide their children with advantages.

Conclusion: “Gentrification is Gensociocide”

By thinking of gentrification as an extension or tool of settler colonialism, it is not hard to see why housing activists have been using the slogan, “gentrification is genocide”.

The same logic that make settler colonialism possible—extraction, expulsions, clearings, genocide, private property, and the family—are the same that make gentrification possible.

In many ways, gentrification is just another way to make settler colonialism visible in the city.