Classical Influences on America’s Founders

“Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” As was believed even at the time, those words of American scripture announced a new beginning in world history. A new nation with a new creed of “unalienable rights” where “all men are created equal.” Yet even the brand new is built upon the old. That’s a lesson Jeffrey Rosen teaches in The Pursuit of Happiness: How Classical Writers on Virtue Inspired the Lives of the Founders and Defined America (Simon & Schuster 2024).

His tour through the lives and reading habits of several American Founders illuminates where the idea of “the pursuit of happiness” came from and, more importantly, how these men (and a few women) applied that same wisdom in pursuing happiness—to various degrees of success—in their own lives. Even those without a special interest in ancient wisdom or America’s founding will find Rosen’s journey an intriguing case study of how one age speaks to another. His book intersects some with his usual beat, constitutional law (he is the President of the National Constitution Center), but less than you’d expect.

Rosen demonstrates how the Founders relied upon the words of the ancients in pursuing eudaimonia and not hedonistic pleasure.

This is not a work of legal analysis or political philosophy. It is an investigation of how those who shaped a new legal order structured their own lives. Nevertheless, it provokes countless questions about that legal order and its subsequent evolution, particularly as it relates to the titular “pursuit of happiness.” At the same time, however, although Rosen provides a rich exploration of how many classical writers influenced the “Founders,” there seem to be some gaps regarding which writers and which Founders. More on those gaps below.

Founding Libraries

The book is divided into mini-biographies of a number of individuals, concentrating on the person’s life story, their reading habits, and how they applied that reading to both their political and scholarly pursuits as well as their personal attempts at self-improvement. We learn about reading lists, contents of home libraries, hourly schedules, and attempts to refine and better those schedules through tweaking and reflection.

No one quite had the opulence of Pliny the Younger’s daily routine, which included arising “when I please,” a walk on the terrace, a chariot ride, a private bath, a nap, dinner with friends, time listening to a private musician, and an evening of “varied conversation.” But still, early risings, reflections, worship (for some), and many hours of reading pushed them toward the good life.

“Commonwealth” contrasted with the tyrannies of Europe where despotism or oligarchy were abundant.

Many readers will know of Benjamin Franklin’s thirteen virtues and his gospel of self-improvement. What I did not know was how so many other Founders had similar, just less advertised, systems of improving themselves. That they drew much of their regime from writers of classical antiquity should not be surprising as familiarity with those writers was far from unusual at the time.

Indeed, in Western societies this was the norm from at least the late Middle Ages—with the rise of universities and non-clerical education in places like Oxford, Paris, and Heidelberg—until the 20th century. This educational regime required students to read the classics of the Greeks and Romans as well as (don’t forget) Christian scripture and the Church Fathers. The pagan classics included the works of philosophers and statesmen such as Plato, Aristotle, Cicero, and Seneca, but also of playwrights and poets, including Euripides, Ovid, and, of course, Homer.

Now, it should be noted that as the stock of human knowledge grew, this system of focusing on the ancients became, no pun intended, somewhat antiquated.

Students of musical comedy will remember Major-General Stanley’s “I Am the Very Model of a Modern Major General,” where the gentleman knows every detail of Caractacus’s uniform but nothing on modern gunnery.

Yet, by-and-large, the Founders were no Stanleys. As Rosen details, in addition to Franklin’s scientific exploits, others kept up with the latest in modern knowledge. And their reading lists were not just from ancient times. John Locke, Algernon Sidney, and the contemporary-to-some David Hume, plus other early modern thinkers, graced the lists as well.

Jefferson’s hypocrisy is well-known and off the charts, but others who spoke of the “pursuit of happiness” depended on owning people to support their happy lifestyles.

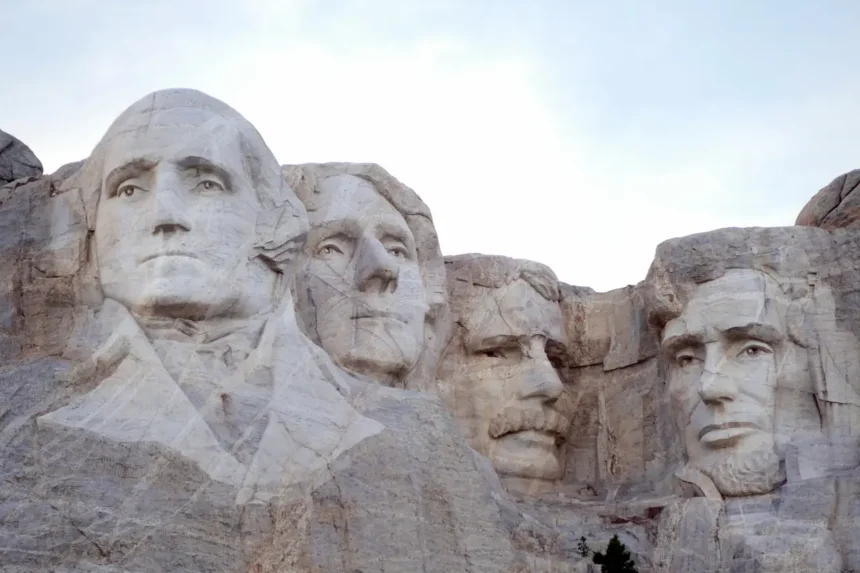

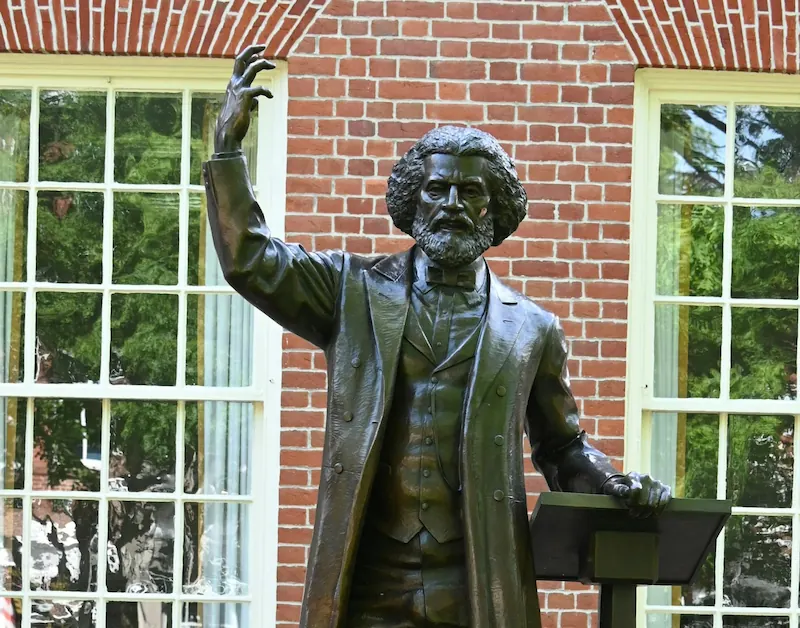

Rosen’s main characters include the usual “Big Six” Founders—Franklin, Jefferson, Washington, John Adams, Madison, and Hamilton—but also a few others—James Wilson, George Mason, and Abigail Adams, plus her and John’s son John Quincy. There’s also a chapter on someone most will be entirely unfamiliar with: Phillis Wheatley, the enslaved woman turned Boston poet whose verse dazzled powerful men from Washington to Voltaire.

There was quite a mix of which ancient writers influenced Rosen’s subjects, although they bended more Roman than Greek and more Stoic than otherwise. Cicero and Seneca come up over and over again, as does Epictetus, a Greek Stoic of the Pax Romana. Aristotle certainly was present in the Founders’ lives as well, but we are left with the impression that the “happiness” of the Nicomachean Ethics was not nearly as important as Cicero’s epistolary missives flung off between failed attempts to save the Roman Republic.

George Mason owned slaves until his death and never freed them even as he abstractly believed in human equality.

Pythagoras, whose ideas only survived antiquity through a patchwork of sources, gets a surprising amount of attention as well. About as much as Plato and Socrates, perhaps more.

These ratios will likely surprise those who have studied what we now call “ancient philosophy” where the curriculum often is almost entirely built around the writings of Plato and Aristotle.

It is a reminder, though, that during “modern times” things were not always so fourth-century-B.C.-centric when it comes to ancient wisdom.

I went through an entire undergraduate philosophy program without being assigned a single Roman philosopher outside of independent study. I always found it not-exactly well rounded, and the statesmen of the eighteenth century A.D. (on either side of the Atlantic) likely would not either. (All that being said, the thinker I found most curiously missing from Rosen’s narrative was another Roman, Lucretius, whose absence is addressed below.)

Divisions of Labor

Whoever exactly these Founders were reading, one detail that Rosen rightly emphasizes is that a look at their diaries reveals mind-bending amounts of time given to reading and contemplation—at least mind-bending to those of us living in the age of social media.

Yet, one reason many Founders—but it should be said not all—enjoyed this luxury of time was not just the lack of distracting devices but enslaved people running the devices they did have at hand—and doing much else. Rosen doesn’t pull any punches in pointing out their slave-owning ways and highlighting the well-known, but worth remembering, hypocrisy so many of them had in relation to the “peculiar institution.”

Jefferson’s hypocrisy is well-known and off the charts, but others who spoke of the “pursuit of happiness” depended on owning people to support their happy lifestyles. For example, George Mason, the author of Virginia’s Declaration of Rights and its mention of a right to pursue happiness, which directly influenced Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, owned slaves until his death and never freed them even as he abstractly believed in human equality.

Jefferson never got around to releasing his slaves because they always were necessary for him to pursue his lavish lifestyle (including the ruinous debts it incurred). This despite the now well-proved family he created with one of them, Sally Hemings.

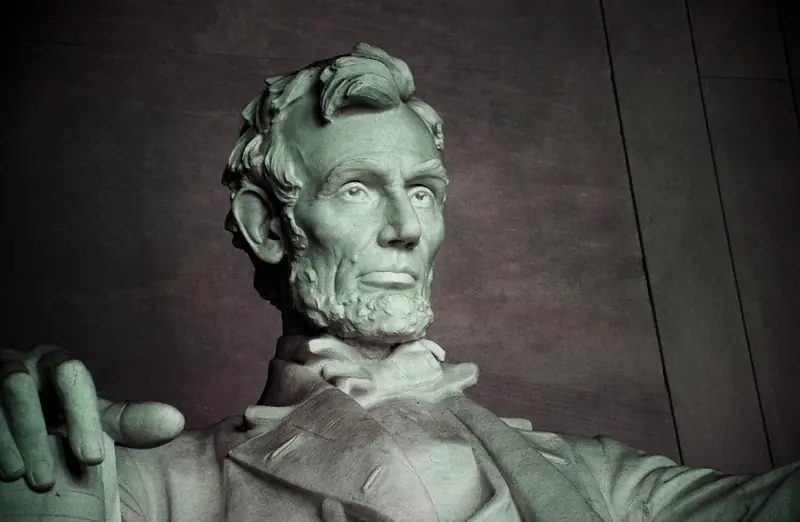

The contradiction between a right to pursue happiness and slavery may be why Rosen includes not just the Founders, but a couple from America’s “Second Founding”: Frederick Douglass and Abraham Lincoln. These men were famously self-taught, something they shared with the one Founder who did free his slaves (upon his wife’s death), George Washington. Nevertheless, Douglass and Lincoln drew from the wisdom of ancient thinkers all the same.

As students of the classics know, ‘happiness’ is an eternally contested concept, although the Founders’ understanding of it had more in common with their Greek and Roman predecessors than with our understanding today. Rosen demonstrates how the Founders relied upon the words of the ancients in pursuing eudaimonia—roughly meaning “the good life”—and not hedonistic pleasure. (That was their ideal, anyway. Some of them pursued plenty of pure pleasure as well—but they didn’t need Cicero for that.) This includes both their personal lives and their statecraft.

Later Founding Effects

Again, Rosen’s investigation is primarily about the Founders’ various personal attempts at eudaimonia, not so much how “the good life” translated into public policy. But he nevertheless touches on the Founders’ understanding that the “unalienable right” “to pursue happiness” meant living in a “commonwealth,” that is, a society whose laws are directed at the wealth of all, not the wealth of one or a few. That did not mean, however, a society committed to wealth redistribution.

Few of the Founders had anything like that in mind, although there were radicals associating with them who harbored those inclinations—Thomas Paine being the most remembered today. “Commonwealth” instead contrasted with the tyrannies of Europe where despotism or oligarchy were still abundant. In short, “commonwealth” meant a society where people had their life and liberty secured so they could go out and pursue their own happiness.

Spinoza and the Epicureans were read by many in Revolutionary America.

This hit home to me because while reading Rosen’s book I was coincidentally completing some research on provisions in state constitutions that protect the “pursuit of happiness” among other rights, including “life,” “liberty,” and “property.” These descend both from the Declaration of Independence and George Mason’s Virginia’s Declaration of Rights.

One example is Pennsylvania’s, which, when adopted just three months after Independence, said “That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable rights amongst which are the enjoying and defending life and liberty, acquiring, possessing and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.” I examined how these provisions were debated in state constitutional conventions throughout American history.

What I found is a centuries-long supplement to the efforts of the Founders. These state-level founders and constitutional framers saw the “pursuit of happiness” to encompass a kaleidoscope of activities, in turn requiring protection of a multitude of individual rights.

Perhaps a delegate at the Kentucky constitutional convention of 1890 said it best when he pointed out that the proposed state constitution protected the rights to life, liberty, and property but that all of these rights “are all embraced in the expression, ‘the pursuit of happiness,’ because that necessarily implies all the balance.” In other words, why do we have all of these different rights and, indeed, all the various mechanics of constitutional government? For the people, individually, to pursue their happiness. Whether or not they enlist Cicero.

Different Thinkers for Differing Founders

I am left with some puzzlement over Rosen’s coverage of the Founders and their reading habits. He is completely upfront that he is not a student of the ancient world—his education was much more modern (as he now seems to regret) than Major-General Stanley’s. In the introduction he details how he only came across the ancients when COVID-19 shut all of us inside.

One thing led to another during this seclusion and he found himself working through one of Jefferson’s reading lists. For me—someone who studied ancient philosophy and classics at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels and then went to American law school to learn of the Constitution and its history—it is a joy to see his newfound boyish enthusiasm for ancient wisdom as a result of this later-in-life discovery.

The full story of Lucretius vs. Cicero at the American Founding is yet to be written.

But his outsider status also may have led him to miss some of the nuance of those ancient writers and their impact in America. Several years ago, I read Matthew Stewart’s 2014 bombshell Nature’s God: The Heretical Origins of the American Republic. In it Stewart, an independent scholar with an academic philosophy background, documents something not too different from Rosen: the influence of ancient writers on some of the Founders.

But the “ancients” had a different emphasis. Stewart focused on members of the Epicurean school of philosophy, especially Lucretius, a first century B.C. Roman. His On the Nature of Things narrowly survived the Middle Ages, despite its deist metaphysics, and influenced many, especially the 17th century rationalist and pantheist Baruch Spinoza. (Readers may be familiar with some of the story Stewart tells from Stephen Greenblatt’s The Swerve (2011).)

Stewart demonstrates how Epicurean ideas, often but not always via Spinoza, made their way to various Founders. This included Jefferson but took strong root in a couple more obscure characters, Thomas Young, a doctor and organizer for the Boston Tea Party, and Ethan Allen, an enterprising Vermonter (and not a much-later furniture store). Young and Allen outright rejected Christianity, instead adopting a very Lucretian deism (more so than Jefferson’s). But it wasn’t just them. Spinoza and the Epicureans were read by many in Revolutionary America.

Rosen hardly mentions Lucretius and the Epicurean school while documenting a massive influence of Stoics and Pythagoreans. The imbalance between the two books is noteworthy. By that I do not mean that either bent any standards or improperly left evidence on the cutting room floor. Some of this is due to a bit of different emphasis. A large part of Stewart’s aim was to document a neglected deist and proto-atheist tradition at the Founding.

In contrast, Rosen is focused on the age’s view of self-improvement. But that contrast cries out for exploration. It seems the full story of Lucretius vs. Cicero at the American Founding is yet to be written. At the least, if Rosen does anything more in this field, I’d love to see him take a look at Stewart’s work or, better yet, have a (hopefully recorded and broadcast) conversation with him. If they need someone, I volunteer to moderate.