Freedom from Fear: An Incomplete History of Liberalism (Princeton, 2023) begins with a definition of liberalism intended both for the average person and the academic: “liberalism is the search for a society in which no one need be afraid”. Specialists will recognize the verbal resemblance to Judith Shklar’s “Liberalism of Fear”, itself derived from Montesquieu, but in fact the book rejects Shklar’s minimalist liberalism both as history and as program.

Freedom from Fear analyzes the fears liberals have historically been most concerned with, which have varied over time. This applies both to what liberals have been afraid of, and to the kinds of individual and groups whose fears liberals have taken into account – the fears of women, Black people, or the poor were not at first central to liberal concerns, but eventually were included.

Liberals must build a new operating system, Liberalism 4.0, to respond to the new challenges of the twenty-first century, or risk seeing liberalism swept into the dustbin of history.

One of the book’s arguments is that, contrary to widespread myth, liberalism has focused on the fears of groups equally with those of individuals. Liberals were as concerned with the freedom of different churches as with the freedom of the individual conscience, with the rights of associations as well as the rights of individuals. Which groups or which type of person liberals took into account is an essential part of the history of liberalism.

Four Fears and Three Pillars

The structure of the book is chronological, based on the “four fears” which dominated liberal concerns in different periods: 1) Religious persecution and absolutism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; 2) Revolution and Reaction, from the American and French revolutions until roughly 1873; 3) Poverty, during the fin de siecle (1873-1919); and 4) Totalitarianism (1920-2000). These four fears concentrated liberal minds, while old fears never entirely disappeared.

Notable throughout the book is the discussion of the “Three Pillars of Liberalism”, that is freedom, markets, and morals, or politics, economics, and morality/religion.

Freedom from Fear argues that until WWII most liberals thought that all three pillars were necessary to build a stable liberal society, and that since the mid-twentieth century there has been a growing tendency to restrict liberalism to one-pillar arguments, typically economic or political/procedural, at the expense of morality and religion, which has weakened liberalism.

Each wave of liberalism had its own preferred technique for warding off the fear of the moment.

- First-wave liberals typically sought to write constitutions that would ward off both revolution and reaction.

- Second-wave liberals built welfare states to fight poverty.

- Third- wave liberals produced technocratic solutions to diminish the appeal of totalitarianism.

Liberals used whatever tools were to hand to fight fear. Rights were often useful tools, but were never in themselves constitutive of liberalism.

Every fear thus gave birth to a new kind of liberalism. First came “proto-liberalism”, “proto” because the word “liberal” had not yet acquired a political meaning. Smith and Montesquieu are the exemplars discussed. Locke is not included because of his minimal historical influence from the 1780s until the mid-twentieth century. Smith and Montesquieu, however, set the stage for the treatment of problems that remained central in the nineteenth century.

Liberalism 1.0 and 2.0: 1800-1919

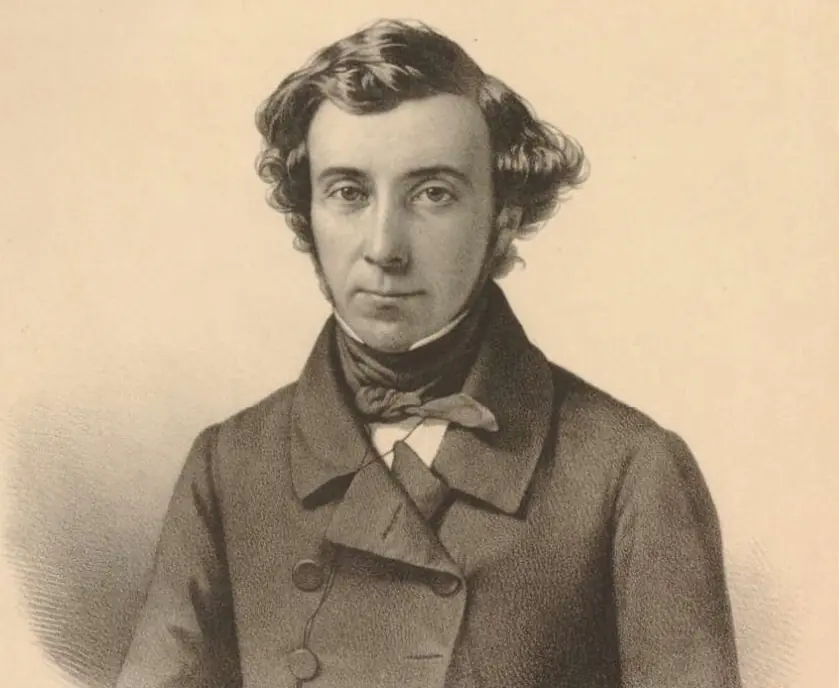

Liberalism 1.0, the first wave of liberalism proper, dominated the short nineteenth century (1800-1873) when liberals typically used three-pillared arguments to fend off revolution and reaction. Kant, Madison, and Constant, feature as its first generation, followed by Macaulay, Tocqueville, and John Stuart Mill. But political traditions can only be understood in context, and afterwards intellectual biography is briefly abandoned to examine how nineteenth-century liberals treated suffrage questions, nationalism, and Catholicism.

Consideration of Liberalism 1.0 closes with a discussion of “Liberalism with Something Missing”, influential liberals who departed from the nineteenth-century mainstream and based their liberalism on a single pillar : Bentham, Bastiat, and Spencer. Liberalism has always been characterized by intellectual diversity.

Liberalism has always been characterized by intellectual diversity.

Liberalism 2.0, which dominated the fin-de-siècle (1873-1919), mostly ceased to fear the poor as revolutionaries or reactionaries and instead saw the poor as people with something to fear.

But fin de siècle liberals split into two camps, “modern liberals” (US Progressives, British New Liberals, French Solidarists, German Social Liberals) who wished to use the State to help the poor, and “classical liberals”, who feared a growing State.

Jane Addams, Léon Bourgeois, L.T. Hobhouse represent variations on the modern liberal argument in the US, France and Britain, while the great English jurist A. V. Dicey illustrates the perspective of classical liberalism, which was much the same everywhere in the Western world. As in Liberalism 1.0, liberals typically continued to make arguments that referred to politics, economics, and morals/religion in defending their point of view, although with more exceptions than before.

The new fear of poverty, however, never entirely eclipsed the older fear of revolution and reaction – indeed some classical liberals feared the struggle against poverty might lead to either. Freedom from Fear argues that the usual metaphors used to write the history of political traditions, the family tree and genealogy, need to be replaced by the analogy of the oyster, whose growth is represented by layers which always remain visible.

Liberalism 2.0 is also explored in the context of some of the leading political debates of the day. These include the relationship of liberalism to fin de siècle nationalism, which liberals found much more problematic than earlier in the century; colonialism, with particular attention to French and German liberal attitudes, and feminism. While the vast majority of nineteenth-century and fin de siècle liberals were not feminists, most feminists were liberals.

Liberalism 3.0: 1920-2000

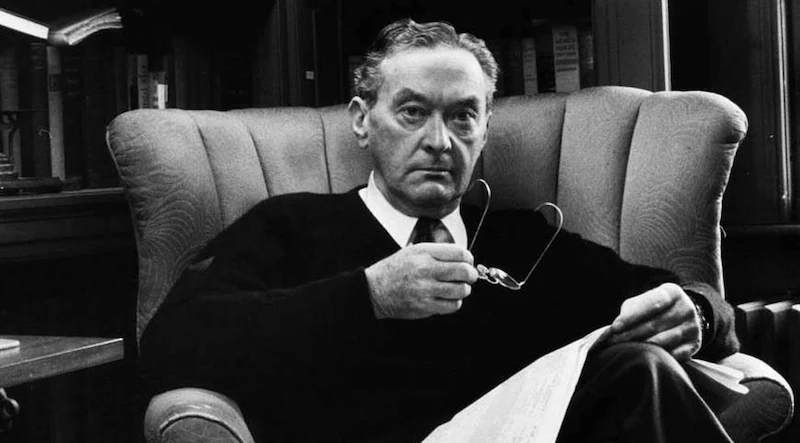

WWI transformed liberalism again. The Great Depression and the rise of fascism and communism made clear that what liberals had most to fear was totalitarianism. To defeat totalitarianism, it was crucial to repair the modern/classical liberal split. Searching for a solution, liberals from throughout the Western world gathered in Paris for the Colloque Lippmann in 1938, named after the American journalist Walter Lippmann, whose The Good Society many found inspiring.

After discussing Lippmann’s work and recounting the Paris discussions, Liberalism 3.0 is explored through the ideas of Friedrich Hayek (one of the organizers of the Paris conference), Isaiah Berlin, and a relatively little known but highly important stream of liberal thought that known as Ordoliberalism. This first generation of Liberalism 3.0 was often, thanks to modern medicine, very long-lived, but their characteristic ideas were formed in the 1930s.

Populism has become the fifth fear to attract the lion’s share of liberal attention.

A second and third generation of Liberalism 3.0 is discussed under the title “Hollow Victories, 1945-2000”.

Liberal victories were hollow in part because they were won, or so it appeared at the time, by hollowing out liberalism, in particular its moral/religious pillar, which was largely abandoned by liberals during this period.

Dropping any kind of moral/religious element from liberalism was the explicit program of the “End of Ideology” movement that dominated Western Liberal thought in the 1950s and early 1960s.

For proponents of the End of Ideology, the totalitarianism of the 1930s was the result of too much utopianism, whether on the right or left, and hence all utopian elements had to be purged from politics in general, and liberalism in particular. This was self-contradictory, because liberalism had always been utopian – no society had ever been fully free from fear, and yet liberals had always striven to attain this utopia.

The rise of populism was fueled in part by the disappearance of the moral pillar from liberal discourse.

This utopian hope had always been as much a part of liberalism as fear – this is why liberalism was so often identified as the party of progress. But for the End of Ideology movement, technocratic tinkering was the solution and the source of such modest further progress as was attainable. The illusion that such a disenchanted world was possible, let alone desirable, was rudely ended by the Civil Rights Movement, the counterculture of the 1960s, and the Viet Nam War.

Beginning in the 1970s, a third generation of anti-totalitarian liberals returned to ideology, although they continued to argue on a much narrower basis than the three-pillar liberalism of Liberalism 1.0 and 2.0. Most famously, John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice inaugurated what he called “egalitarian liberalism”, which went beyond the anti-poverty program of modern liberals to espouse a demand for substantial equality as necessary to a society which would live without fear.

In reaction, Robert Nozick penned Anarchy, State, and Utopia, the philosophical underpinnings for Libertarians who saw themselves as the true heirs of classical liberalism. Discussion of the Rawls/Nozick debate is followed by consideration of the economistic neoliberalism of Milton Friedman, and the much more modest liberalism of fear endorsed by Judith Shklar and Bernard Williams.

Liberalism vs. Populism Today: Towards Liberalism 4.0?

With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, it appeared as if the only remaining political debate in the Western world was between different variations on liberal themes. But the celebratory period was brief, and the rise of illiberal populisms soon revealed the liberal victory to be hollow.

Liberalism 3.0 was shown to be inadequate to the stormy present, and the search for Liberalism 4.0 has commenced. Populism has become the fifth fear to attract the lion’s share of liberal attention.

Definitions of populism vary widely, but they have one thing in common: populism is always seen as illiberal. There is a simple reason for this. Populists always want to make some people afraid, those seen as not really part of the nation, in particular two groups at opposite ends of the social spectrum, immigrants and “elites”.

The rise of populism was fueled in part by the disappearance of the moral pillar from liberal discourse. Human nature abhors a moral vacuum, and populists rushed in to fill it.

The book concludes with a study of the rise of populism and a discussion of what liberals can do about the overlapping illiberal consensus, the alliance of nationalists, religious fundamentalists, and anti-globalists that has arisen almost everywhere.

One suggestion is that liberals need to return emphasizing all three-pillars, freedom, markets, and morals, as they did in the nineteenth century. Liberals need to do more than suggest political procedures and give people the right to choose, without having anything at all to say about what choices they think might be good ones.

The triumph of liberalism, despite what so many people thought in the 1990s, is not inevitable. An illiberal world is possible. Liberals must build a new operating system, Liberalism 4.0, to respond to the new challenges of the twenty-first century, or risk seeing liberalism swept into the dustbin of history. Freedom from Fear makes no pretence of neutrality. It is not just a history of liberalism, but a liberal’s call for a new kind of liberalism.

In this struggle, liberals have one thing on their side: no one wants to be afraid.