About the book From Click to Boom: The Political Economy of E-commerce in China by Lizhi Liu. Published by Princeton University Press, in 2024.

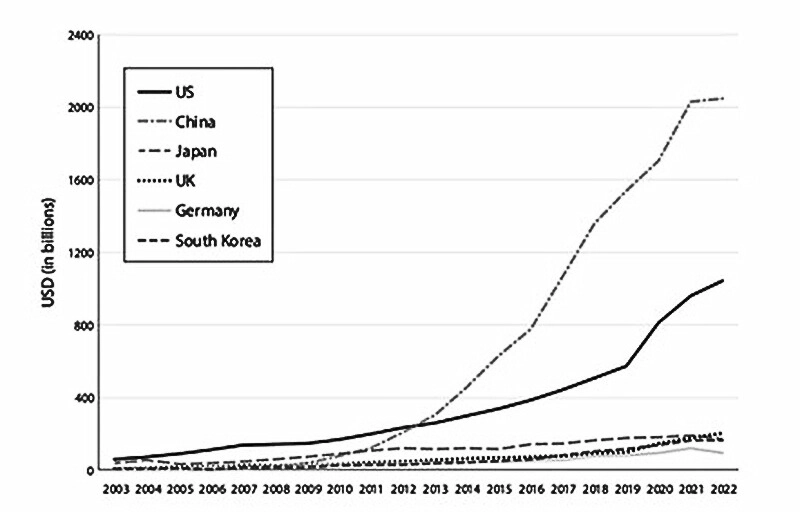

In merely 20 years, China leapfrogged developed economies to build an e-commerce market with 800 million users, capturing nearly 50% of global online retail sales. This ‘everything market’ offers it all—from common products to distressed assets like Boeing 747s and unfinished skyscrapers, alongside quirky items like a ‘Dog Translator’ and a ‘Noisy-Neighbor Revenge Machine’ that vibrates the ceiling of loud upstairs neighbors.

This e-commerce boom, however, seems to defy conventional wisdom. Compared to offline transactions, e-commerce requires very strong institutions for contract enforcement and fraud prevention, as transactions aren’t face-to-face and often involve distant, anonymous traders. Yet, China’s e-commerce market surged without strong legal support; low credit card adoption and rampant counterfeits further eroded consumer trust—factors that should have hindered growth.

A case study on China’s e-commerce market in the 2000s highlighted this point: “China lacked norms and laws regulating online behaviors and preventing online fraud . . . In the US if you place a bid, it’s a contract, and by law you need to fulfill that bid if you win the auction. That’s very clear. People would be afraid of getting sued if they did not abide by that contract. In China people don’t care. ‘I place a bid, I don’t want it anymore, tough luck.’ ”

This book invites readers to reconceptualize digital infrastructures—not merely as technological advancements, but as transformative forces that are redefining governance, market access, and the trajectories of global development.

So, how did China’s e-commerce boom occur without a strong rule of law? Why did China leapfrog Western countries in e-commerce, despite the latter having stronger legal frameworks and higher income levels? Where did the key institutions necessary to foster e-commerce come from?

My answer is institutional outsourcing—a public-private collaboration in institutional development. When the government falls short of providing formal institutional support, it strategically outsources parts of institutional development and enforcement to digital platforms.

Private Institutional Building by E-Commerce Platforms

The first dimension of institutional outsourcing involves the private development of digital institutions. In the context of weak rule of law during the 2000s, Chinese e-commerce platforms were compelled to build powerful online institutions for trust and enforcement—often surpassing their Western counterparts in complexity. For instance, Alibaba’s Taobao developed a comprehensive ecosystem of digital institutions, including an escrow payment system, return shipping insurance, credit scoring, rule hearings, and an online jury for dispute resolution.

Taobao even introduced a “House of Representatives for Rules,” a platform that allowed users to vote on non-essential platform regulations. These innovations were widely adopted by other platforms and ultimately shaped government institutions.

In some cases, the Chinese government leveraged these private mechanisms to enhance legal enforcement or even formalized widely adopted platform rules, including third-party payment systems and seven-day return policy.

It is crucial to acknowledge that, in Western countries, platforms such as Amazon or eBay also incorporate private institutions for contract enforcement or fraud prevention.

However, these institutions are not as sophisticated as their Chinese counterparts due to lower demand. China’s weaker underlying legal enforcement results in a higher prevalence of counterfeiting and fraud. Consequently, platforms in China face greater challenges in earning user trust and facilitating trade on their platforms.

To overcome these obstacles, they must develop much stronger institutions and enforcement capabilities. The need for stronger institutions is illustrated in Chapter 3 through the Taobao-eBay battle in the Chinese market of the early 2000s.

Despite regulatory shifts, the outsourcing of institutional functions from the state to platforms has endured.

eBay’s transplanted institutions from Western countries proved insufficient to assure Chinese users of the safety of online transactions. In contrast, Taobao’s focus on trust-building was the main reason it defeated eBay, despite eBay’s first-mover advantage and much greater resources.

That said, the digital institutions established by Chinese platforms were far from flawless.

As discussed in the book, enforcement capabilities remained limited, and users frequently found ways to game the system—for instance, by manipulating online reviews.

Despite these shortcomings, these digital institutions represented a significant improvement over the counterfactual scenario: the absence of effective institutional frameworks. This digital approach to institutional development offered a second-best solution to governance challenges in contexts where state institutions proved inadequate.

The State’s Outsourcing

Meanwhile, the authoritarian government either acquiesced and gave implicit consent to platforms’ private institutional building (de facto outsourcing), or explicitly delegated institutional functions to digital platforms through formal contracts or agreements (de jure outsourcing).

Initially, the government adopted what I term “strategic non-regulation,” giving implicit consent to platforms’ institutional development. Despite possessing both the regulatory capacity and a clear understanding of e-commerce’s challenges, the government refrained from imposing heavy regulations on the e-commerce industry. For instance, in 2015, the rapid rise of e-commerce led to widespread closures of brick-and-mortar stores, sparking harsh criticism and claims that the digital economy posed a “virtual” threat to the “real” economy.

The study reveals how e-commerce transformed various aspects of China’s economy and governance.

However, the government resisted these pressures and refrained from implementing strict regulations. This deliberate “non-action” was a key driver of the e-commerce boom — unlike proactive industry policies such as providing land or capital, “strategic non-regulation” grants a sector the autonomy it needs to foster growth.

Over time, a more formalized outsourcing model emerged. Through extensive collaborations and formal agreements, central and local governments began delegating various functions to digital platforms in areas such as legal enforcement and economic governance. For example, China’s Anti-Corruption and Bribery Bureau signed a memorandum of understanding with Alibaba, entrusting it with certain legal functions to combat commercial bribery. Platform companies also played a crucial role in shaping regulatory frameworks by contributing to the drafting of the e-commerce law and the establishment of cyber courts.

The Regulatory Dilemma

This digital path to development—outsourcing institutional functions to platforms—comes with its own set of challenges. This approach relies on large platforms having the autonomy to govern and experiment with institutional rules. However, platforms’ growing influence raises suspicions within an authoritarian government. Additionally, as these platforms expand, they introduce various issues, including privacy concerns and anti-competitive practices.

The core dilemma is that inadequate regulation allows platforms to abuse their market power, while heavy-handed regulation stifles institutional innovation by platforms. China’s regulatory oscillations toward platforms underscore the struggle to strike the right balance. Initially, until late 2020, the Chinese government maintained a hands-off approach with minimal regulations. Then, between late 2020 and mid-2023, there was a severe crackdown on big tech companies. Finally, in mid-2023, the government eased regulations and returned to a supportive stance.

Despite these regulatory shifts, the outsourcing of institutional functions from the state to platforms has endured. As Chapter 6 indicates, in some cases, government-platform collaboration even deepened following the crackdown.

Far-reaching Impacts of E-commerce

In addition to analyzing the institutional foundations of China’s e-commerce boom, the book explores its far-reaching effects. Drawing on extensive interviews, original surveys, tens of millions of proprietary data points, and a rare field experiment conducted across three Chinese provinces, the study reveals how e-commerce transformed various aspects of China’s economy and governance.

Chapter 4 investigates how e-commerce reshaped state-business relations, creating new informational and coordination challenges for local governments. Chapter 5 leverages a unique opportunity to conduct a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in collaboration with an e-commerce platform, examining the impact of e-commerce access on rural household welfare.

Chapter 6 delves into China’s regulatory crackdown on the tech sector from 2020 to 2023, arguing that it resulted from a situation in which platforms ‘overstepped’ their bounds, prompting an ‘overreaction’ from the state. The chapter further explains why tech crackdown began in late 2020, suggesting that overconfidence from both the government and tech companies led to the collision.

Digital Institutions Matter

The importance of institutions has been widely recognized, though the focus has traditionally centered on government institutions. In the digital era, however, firm-provided digital institutions have become equally pivotal, shaping not only economic activity but also the fabric of daily life and political dynamics.

This book invites readers to reconceptualize digital infrastructures—not merely as technological advancements, but as transformative forces that are redefining governance, market access, and the trajectories of global development.