“Go woke, go broke” is a risk many CEOs are no longer willing to take. When Walmart recently announced a retreat from its DEI programs, the company followed the likes of John Deere and Molson Coors and many other household names. Similarly, on Wall Street winter has come for ESG investing.

- Corporate Social Responsibility and its Long Past

- Milton Friedman and the Politics of Corporate Social Responsibility

- Adam Smith and Greenwashing before Greenwashing

- CSR in the 1970s: Civil Rights, the Consumer Interest and the Environment

- Plural Publics and the Political Nature of the Corporation

- Future Issues: Business Power and Neomercantilism

In their place is a new emphasis on the less politicized terms “inclusivity” and “sustainability.” At the same time, the innocuous “responsible business” is substituting for the broader rubric of corporate social responsibility (CSR).

Is corporate social responsibility over as a guiding managerial principle or instead transforming into something different?

Corporate Social Responsibility and its Long Past

History suggests a cyclical pattern. Scholars have recently turned to reconstructing the historical development of Corporate Social Responsibility, its legal frameworks and political consequences. Ups and downs are part of the story as is the evolution of the meaning of business and social responsibility. My recent research examines one of the pivotal texts in this history with implications for current debates.

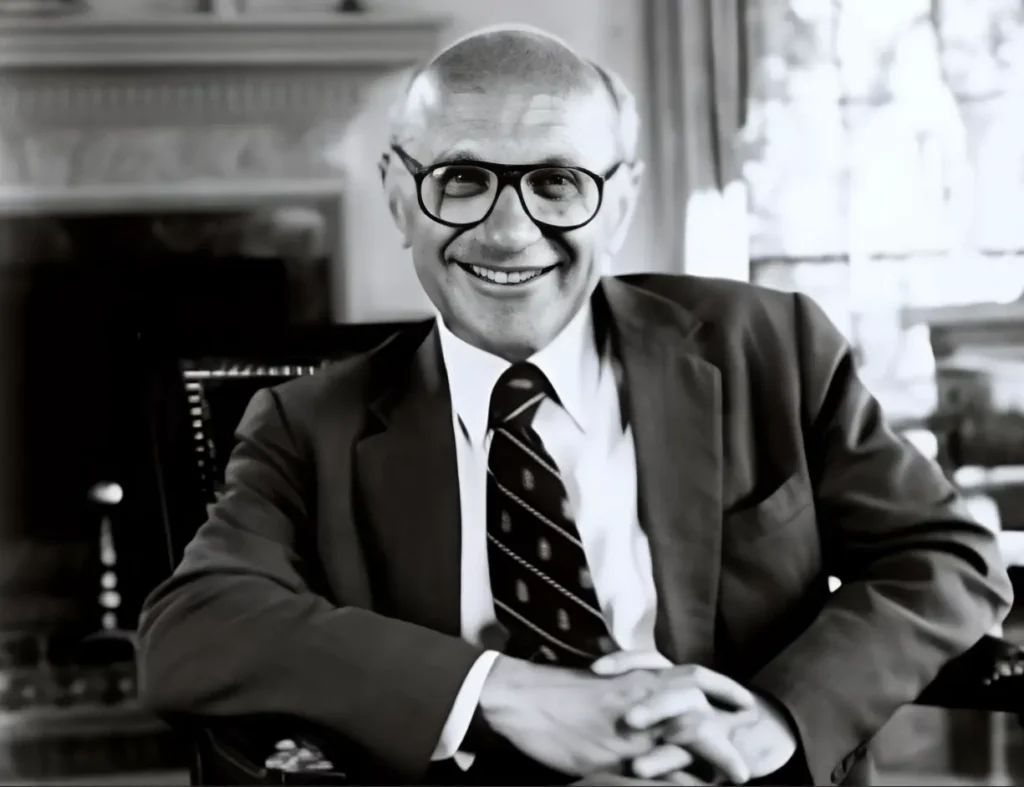

Milton Friedman’s most famous criticism of Corporate Social Responsibility was published in the New York Times Magazine in 1970. His op-ed came at an important point in the history of Corporate Social Responsibility as a managerial practice.

Although anticipated in earlier decades by movements to make business more ethical, Corporate Social Responsibility as a distinctive concept began to flourish among academics during the 1950s and was well-established more widely by the 1970s.

During the 1980s CSR usefully contrasted with the “shareholder primacy” paradigm (also associated with Friedman though his influence has been questioned).

Between these two corporate governance models lay the question of whether managers should prioritize the financial interest of shareholders over other stakeholders? Consultants and academics found a solution in the “business case for CSR.” Corporate Social Responsibility, they argued, could also improve the bottom line or as the catchphrase went, “do well by doing good.”

ESG and DEI operationalized CSR strategies by introducing specific metrics to align “people, planet and profit” with the “triple bottom line” (more catchphrases). By the 2010s this approach was increasingly fashionable. Backlash followed.

Milton Friedman and the Politics of Corporate Social Responsibility

This backlash should come as little surprise to careful readers of Milton Friedman, who had assembled a battery of arguments against Corporate Social Responsibility. Until recently there was some doubt over the continuing relevance of his claims. Friedman has, in fact, had a counterintuitive influence on CSR. His willingness to accept that a corporation could engage in social responsibility if it strengthened its bottom-line anticipated the “business case” for CSR.

Moreover, the clarity of his arguments place into relief the political tensions involved when businesses seek to be socially responsible. These led Friedman to conclude that business and social responsibility was a “fundamentally subversive doctrine” that “does not differ in philosophy from the most explicitly collectivist doctrine.”

Friedman had been publishing his criticisms for at least a decade prior to 1970, but his arguments changed along with CSR. Initially, Friedman associated Corporate Social Responsibility with post-war corporatism or the alignment between business, labour and government. He believed that social responsibility was a mechanism that businesspeople used to suppress competitive markets.

Business interests captured or worked with regulators under the guise of the public interest to make rules that favoured incumbents and protected monopolies or oligopolies by erecting barriers to entry. His frequent examples included the Federal Communication Commission and the Interstate Commerce Commission. Why play by the rules of the game when you can set them?

Friedman consequently railed against claims about social responsibility coming from the mouths of executives as “hypocritical window-dressing” or what would now be described as “greenwashing.” Friedman, moreover, rooted his criticism of modern CSR as a tool of powerful businesses in a much longer tradition within classical liberalism.

Adam Smith and Greenwashing before Greenwashing

In speech after speech, in private correspondence and notes, Friedman pointed to his source – Adam Smith. During the eighteenth century Smith had argued against the “mercantile system” of protectionist legislation and monopolies in Britain.

His claim was that business interests had erected this system and its labyrinthine laws to suppress competition and enhance their profits. They had done so, explained Smith, under the guise of the “public interest” by persuading legislators that “that the private interest of a part, and of a subordinate part of the society, is the general interest of the whole.”

Corporations are communities of stakeholders and they are also entities that act politically.

Smith’s neoliberal successors took up this line of criticism in the twentieth century, introducing a largely overlooked suspicion of business into their thinking.

This made sense: during the 1930s and 1940s, they lived in a world where large-scale businesses had increasingly close relationships with governments as their societies recovered from the Great Depression and made war.

Friedman’s early criticisms of Corporate Social Responsibility largely assumed that business used social responsibility to manipulate its external environment or those regulatory and political frameworks that governed markets.

CSR in the 1970s: Civil Rights, the Consumer Interest and the Environment

But by 1970 times were a-changing. So was Corporate Social Responsibility and in ways pertinent to today’s complaints about DEI and ESG. The American cultural environment had transformed during the 1960s and along with several business scandals, had led to growing doubts about the trustworthiness of large American corporations.

The modern environmental and civil rights movements had also shifted the expectations about business conduct. Corporate managers responded, sometimes galvanized by a desire to have their companies contribute to social ends by alleviating poverty, improving equal access to employment opportunities, lessening pollution. Sound familiar?

The degree to which the historical developments of CSR can be a guide to emerging debates over corporate power and social responsibility remains to be seen.

During the same period, activists increasingly sought to compel executives to embrace social responsibility. The editors of the New York Times Magazine framed Friedman’s op-ed as a commentary on Campaign GM (mentioned parenthetically in the article). Campaign GM was an effort by activists who purchased a dozen shares of the automaker to influence GM to create a “committee for corporate responsibility.” They also wanted the company to refrain from business activities “detrimental to the health, safety, or welfare of the citizens of the United States.”

Friedman’s criticism of CSR in 1970 was timely because he also explored how social responsibility politicized internal corporate decision-making. Social responsibility, he argued, “involves the acceptance of the socialist view that political mechanisms, not market mechanisms,” should guide economic allocation. The political mechanism, Friedman argued, would override the signals produced by the market in the decision-making of corporate managers.

Managers would pursue various social goals with wide discretion but were poorly suited to the task: if they sought to fight inflation, how were they “to know what action… will contribute to that end?” Minorities of shareholders (or, as Friedman put it, “the recent G.M. crusade”) might also influence or compel managers to make decisions that were not in the financial interests of shareholders or the company itself. This is why Corporate Social Responsibility led to socialism.

Plural Publics and the Political Nature of the Corporation

In making these arguments, Friedman underscored the problem of CSR and the plurality of publics that inhabit democracies. They do not always, or often, agree on what constitutes a shared public interest. Managers and executives, Friedman argued, were particularly ill-equipped to figure out social or public interests, and were often tempted to act cynically.

The razor-edge of the problem, however, was that when one group of shareholders or executives claimed to act in the social or public interest, their critics could argue that they were, in actuality, pursuing narrowly sectional or self-interested goals. They were imposing their values on others. “Go woke, go broke” is a conflict between these two meanings: the pursuit of a general, public interest is reframed by opponents as a sectional interest that operates coercively.

Neomercantilism has its own flavour of Corporate Social Responsibility.

The second issue that Friedman highlighted was the problem of the political character of the corporation. We might assume that business corporations are economic entities concerned with transaction costs and profits. But today there is increased awareness both in the CSR field and the corporate law literature of the political characteristics of business corporations. Corporations are communities of stakeholders and they are also entities that act politically. A recent conceptual trend in the CSR literature, for example, has been to examine “political CSR” or the possibility that business corporations might fill functional governance gaps or voids left by the weakness of state governance.

Corporations are also political actors. This is most obvious because they lobby extensively, a trend that accelerated in the United States in the 1970s, and they financially contribute to candidates whose agendas are favorable to their businesses. Even more pronounced, however, is the power of corporations to shape political opinions and beliefs by constituting publics or identity groups on technology platforms that sort viewpoints.

Future Issues: Business Power and Neomercantilism

Friedman wasn’t as naïve as is sometimes supposed about the threat to democracy posed by concentrations of economic power and the anticompetitive instincts of businesspeople. But he also didn’t provide much of a solution to the problem. Recent writers have observed the weakness of political thought in much Anglo-American neoliberal writing.

German ordoliberals, in contrast, developed a more robust set ideas around economic constitutionalism. The problem has come home, however, signaled both by the resurgence of the modern antitrust movement and calls to study the impact of business power within American constitutional thought and business history.

This agenda is, arguably, now one of the most important civic issues of our time.

This is an issue that will also intensify with the expansion of neomercantilist thought and other nationalist political economies. The use of governmental power to promote specific businesses and markets against foreign rivals, tilting the playing field to favour the home team, also has a long, if recently underappreciated, history. Neomercantilism has its own flavour of Corporate Social Responsibility. In a militarily and ideologically rivalrous world social responsibility may well become located in critical supply chain management, the control of key technologies, and the championing of national interests.

The degree to which the historical developments of CSR can be a guide to emerging debates over corporate power and social responsibility remains to be seen. But they do demonstrate cyclical patterns that echo, even if they do not replicate, current tensions.