Mishima Yukio remains a singularly provocative and influential figure in the landscape of Japanese literature and politics. His extensive oeuvre, which includes novels, plays, and essays, is characterized by a profound exploration of themes such as beauty, mortality, and the complexities of personal and national identity. Mishima’s life, which ended in a dramatic and highly publicized act of seppuku in 1970, epitomizes the contradictions and tensions that permeate his literary works.

At the heart of his narrative universe is the intricate weaving together of homoeroticism with a fervent, and often contentious, nationalism. This juxtaposition offers a unique lens through which to examine the interplay between private desires and public ideologies, especially through Mishima’s idealization of the Emperor of Japan and his vision for the nation.

Through his life and work, Mishima challenged the boundaries of political and sexual identity.

This article endeavors to unravel these complex themes, aiming to shed new light on Mishima’s contributions to both Japanese literature and political discourse. By examining how Mishima’s personal leanings towards homoeroticism are intertwined with his nationalist sentiments, I seek to uncover the deeper implications of his fascination with the emperor and the state. This exploration is vital for grasping the broader ramifications of Mishima’s work, including how it confronts traditional perceptions of sexuality, loyalty, and identity.

Through this analysis, I aim to both illuminate Mishima’s literary and political legacy and engage with the intricate fabric of post-war Japanese society. This approach intends to provide a thorough understanding of Mishima’s lasting impact and the persistent relevance of his inquiries into the essence of devotion—to both one’s nation and one’s innermost yearnings.

Mishima’s Political Ideology

Mishima Yukio’s literary career was deeply intertwined with his complex political ideology, marked by an unwavering nationalist sentiment and an idealized reverence for the Emperor of Japan. This section delves into the intricate fabric of Mishima’s nationalist views, characterized by a fervent belief in the sacredness of the emperor and the nation.

Unlike the prevailing political narratives of post-war Japan, which largely embraced pacifism and democratic principles under the influence of the American occupation, Mishima’s ideology harked back to a romanticized pre-war era. He envisioned a Japan that upheld the traditional values of the samurai, emphasizing honor, loyalty, and the ultimate sacrifice for the emperor and country.

Mishima’s political stance was not just a nostalgic yearning for the past but also a critique of the contemporary society he saw as emasculated. He believed that the post-war pacifist constitution, which renounced war and diminished the emperor’s role to a mere symbolic figurehead, had led to a loss of national identity and strength. In his view, the restoration of the emperor’s divine status and the rekindling of the bushido spirit were essential for Japan’s resurgence as a formidable nation.

This ideological divergence from mainstream politics was not merely theoretical for Mishima. He took tangible steps to manifest his beliefs, most notably through the formation of the Tatenokai, a private militia composed of young men dedicated to traditional martial values and the defense of the emperor.

Mishima’s ultimate act of protest — his dramatic suicide by seppuku at the Japan Self-Defense Forces’ headquarters — was a culmination of his homoerotic nationalism, symbolizing his despair over Japan’s deviation from its imperial legacy and his personal devotion to an idealized notion of beauty and sacrifice. Through his life and work, Mishima challenged the boundaries of political and sexual identity, weaving his homoerotic desires with his nationalist fervor in a provocative tapestry that continues to fascinate and perplex.

Homoerotic Nationalism in Mishima’s Literature

Mishima Yukio’s exploration of homoerotic themes in his literature shifted from an aesthetic choice to a profound expression of his political and personal ideologies. In “Confessions of a Mask,” Mishima delves into the life of a young man grappling with his homosexuality in a society that stifles individuality and non-conformity. The protagonist’s internal conflict and his mask-wearing metaphor highlight the tension between personal desires and societal expectations. The protagonist’s journey mirrors Mishima’s quest for a personal identity who struggled with his own queer desires.

Homoerotic nationalism in Mishima’s works serves as a provocative intersection of personal desire and political ideology.

“The Temple of the Golden Pavilion” further exemplifies Mishima’s use of homoeroticism to critique cultural and aesthetic decay. The novel’s protagonist, obsessed with the beauty of the Golden Pavilion, embodies Mishima’s fear of the loss of beauty and traditional values in modern Japan. His destructive impulse towards the temple symbolizes a rejection of the flawed reality in favor of an idealized, unattainable beauty. This act of destruction resonates with Mishima’s nationalist fervor, wherein the destruction of the post-war societal fabric is a necessary step towards resurrecting a Japan that aligns with his idealized, homoerotically charged vision of the nation.

Homoeroticism can become a direct criticism against postwar Japan and the emperor. Mishima’s novel, “Voices of the Heroic Dead”, expressed the sorrows of the dead soldiers of the February 26 incident, and of the kamikaze pilots (Tokkōtai) who confessed their love for Emperor Hirohito, but criticized him, along with post-war Japanese society, through a spiritualist medium. The dead soldiers’ voices accuse Hirohito of his denial of divinity. Mishima represented the voices of dead soldiers who were “betrayed” by his Humanity Declaration, which “nullified” both the meaning of their sacrifice and the foundation of Japanese militant masculinity. At the same time, Mishima disdained the postwar Japanese society, which was peaceful and economically flourishing, as symbolized by the success of the Olympics in Tokyo in 1964.

Through his literature, Mishima employs homoeroticism not just as a thematic element but as a critical tool to navigate and articulate his complex ideologies. Homoerotic nationalism in Mishima’s works thus serves as a provocative intersection of personal desire and political ideology, offering a unique perspective on identity, beauty, and loyalty in the context of Japan’s tumultuous transition into the modern era.

Nationalism and Queer Desire

The fusion of nationalism and queer desire in Mishima Yukio’s life and work reflects a unique synthesis of personal and political ideologies against the backdrop of mid-20th century Japan. Mishima’s writings and public persona navigated the complex interplay between his queer identity and fervent nationalist beliefs, a journey marked by both controversy and admiration. This intertwining of homoerotic nationalism offers a profound lens through which to understand Mishima’s critique of Japanese society and his idealization of the past.

During Mishima’s lifetime, Japan underwent significant transformations, emerging from the devastations of World War II to embrace rapid economic modernization and democratization. This period saw a tension between Japanese existing social order, including the reverence for the emperor and the nation, and the new adoption of Western democratic ideals. Mishima’s expression of queer desires, explored through his literature and political activism, was controversial for its time. He was a popular artist but sometimes ridiculed from conservative Japanese society.

Mishima’s nationalism, deeply rooted in the idealization of the samurai and the imperial cult, was at odds with the prevailing societal norms that were increasingly adopting Japan’s pacifist role and the traditional values Mishima cherished. His queer desire added another layer of complexity to his nationalist pursuits, as it reconstructed Japanese masculinity.

Beyond the political, the emperor’s symbolism extends into the realm of Mishima’s homoerotic desires.

Mishima’s valorization of male beauty and strength, and his depiction of intense male bonds in his works, can be viewed as a form of homoerotic nationalism that celebrated an idealized, masculine Japan while also critiquing its contemporary decay and loss of identity.

The societal and historical context of Japan during Mishima’s era was characterized by a relative silence on queer issues, with neither widespread acceptance nor overt persecution. This ambiguity allowed Mishima’s exploration of queer themes within his nationalist framework, albeit without directly challenging the deeply ingrained societal norms. Mishima’s life and work, embodying the fusing between his queer desire and nationalist beliefs, offer a unique perspective on the complexities of sexuality and nationalism in Japan, revealing the nuanced ways in which personal identities can intersect with and inform political ideologies.

The Emperor’s Symbolism

In Mishima Yukio’s intricate narrative universe, the emperor emerges not merely as a figurehead but as a profound symbol intertwining the political with the deeply personal, especially within the context of homoerotic nationalism. This symbolism is multifaceted, encapsulating Mishima’s yearning for a return to traditional values, his critique of post-war Japan’s de-masculinization, and his complex erotic desires. Through the emperor, Mishima navigates the realms of political ideology, personal queer desire, and aesthetic expression, making this symbol a cornerstone of his philosophical and literary exploration.

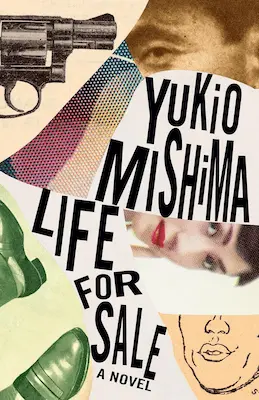

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

The emperor, for Mishima, represented the epitome of Japanese identity and continuity, embodying the nation’s soul and its unbroken lineage. This reverence is deeply intertwined with Mishima’s nationalist sentiments, reflecting his idealization of a Japan that maintains its cultural purity and resists the diluting influences of leftist movements in the 1960s and political dependence on the US. In his works, the emperor is often idealized as a figure of transcendent beauty and moral authority, a living deity whose presence sanctifies the nation and its people. This sacralization of the emperor is a key component of Mishima’s political ideology, advocating for a return to the nation where the emperor’s symbolic authority is paramount.

Mishima’s nationalism allowed him to negotiate his queer personality with the national ideal.

Beyond the political, the emperor’s symbolism extends into the realm of Mishima’s homoerotic desires. The aestheticization of power and the male form in Mishima’s works often converge on the figure of the emperor or what he represents—a convergence of strength, beauty, and purity. This idealization carries homoerotic undertones, where the emperor’s symbolic politic becomes a site of desire, a focal point around which Mishima’s narratives of longing, beauty, and destruction orbit. This intertwining of the political and the erotic underlines Mishima’s belief in the inseparability of body and state, personal desire and national destiny.

The implications of this symbolism are vast, offering insights into not only Mishima’s complex worldview but also his sexuality issues. It reveals his struggle with Japanese heteronormativity, his critique of Japan’s post-war identity, and his quest for a radical national reform that he thought the emperor could offer. This dual symbolism of the emperor as both a political and personal ideal allows us to understand Mishima’s work as a quest for meaning in a heteronormative world as a queer artist who adored Japanese masculine traditional values but was alienated from the Japanese masculine ideal.

Thus, the emperor in Mishima’s oeuvre is more than a character or a symbol; he is the nexus of Mishima’s personal battles, a beacon of national identity, and a canvas for erotic imagination. Through this symbol, Mishima articulates his vision of homoerotic nationalism, where the love for one’s nation and for the emperor transcends conventional boundaries, blending political fervor with the quest for beauty and erotic fulfillment.

Conclusion

Mishima Yukio’s literary and philosophical endeavors intricately intertwine nationalism with homoerotic themes, coalescing into what has been identified as “homoerotic nationalism.” This fusion not only marks Mishima’s narrative and ideological landscape but also casts a revealing light on the socio-political contours of post-war Japan.

Mishima’s nationalism—steeped in a veneration for the emblematic significance of the emperor—allowed him to negotiate his queer personality with the national ideal. This longing transcends mere political ideology, venturing into the realms of aesthetics and erotic desire. Mishima’s works, through their focus on the male form and the embodiment of authority, articulate a vision of Japan that is simultaneously pure, aesthetically sublime, and steadfast, which transnationally fascinate contemporary far-right activists. Yet, this vision is fraught with contradictions, mirroring the broader tensions between tradition and modernity, personal queer identity and heteronormative collective ethos.

The integration of homoeroticism with nationalist sentiment in Mishima’s narratives disrupts traditional dichotomies between sexuality and political ideology, suggesting a complex, intertwined relationship. This synthesis invites a reevaluation of how we understand individual and national identity, challenging us to consider the ways in which personal desires and political beliefs can inform and reshape each other.

Reflecting on the broader implications of Mishima’s work offers profound insights into Japanese political and social dynamics. It underscores the nuanced ways in which Japan grappled with its post-war identity, oscillating between Western influences and a reassertion of traditional values or de-masculinization by the defeat of Pacific War and new identity as an economic leader. Mishima’s “homoerotic nationalism” serves not only as a testament to his personal struggles and ideological convictions but also as a lens through which the complexities of Japanese society—its past, present, and future—can be discerned. Through Mishima, we gain a deeper understanding of the intricate dance between the desire for an idealized past and the realities of a modern, globalized world.

Adapted from an academic article for a wider audience, under license CC BY 4.0