In the communist era of Albania (1944-1991), the introduction of the New Man concept in the 1950s marked a significant paradigm shift in the essence and identity of its populace. Deeply rooted in the tenets of Marxist-Leninism, this concept was not just an ideological statement but a call for a comprehensive reformation of societal values and individual identities. This process of “Anthropological Revolution” was clear and ambitious: to forge citizens into paragons of communist virtue, marked by their absolute devotion and unwavering allegiance to the state and its ideology.

This venture transcended conventional political reforms, delving into the realm of cultural and psychological transformation. It aimed to weave the principles of communism into the very fabric of individual and collective consciousness, thereby reconstructing the societal ethos at its core. The leadership of the Communist Party in Albania, which was renamed the Party of Labour of Albania (PLA) in 1948, sought through this initiative to create an environment where the attributes of the New Man were not merely encouraged, but became the defining characteristics of society. This profound endeavor was aimed at solidifying the ideological bedrock upon which the state stood, endeavoring to create a populace that was not only compliant but actively embodying the values and visions of the Party-State regime.

Forging the New Man: Ideological Education and Labor

In the pursuit of creating the New Man in Albania, the regime strategically employed ideological education and labor as twin pillars of transformation. Education was envisioned as a powerful tool for liberating minds from capitalist influences, designed to inculcate the values of socialism and foster a deep-seated devotion to the state. The educational system, permeated with Marxist-Leninist doctrines, sought to mold young minds into embodiments of the communist ideal. This process extended beyond mere academic instruction, encompassing a holistic approach to reshape thought, behavior, and allegiance.

Individual desires and preferences were subordinate to the collective will

Labor, juxtaposed with education, was elevated to a status beyond mere economic necessity. It was portrayed as a moral imperative, a manifestation of ideological commitment. Every act of labor undertaken by the citizens was imbued with political significance, seen as a direct contribution to the collective good and the advancement of socialist ideals. In this context, work was not just a means of livelihood but a vehicle for expressing loyalty to the regime and internalizing the characteristics of the New Man.

Through these concerted efforts in education and labor, the Party-State endeavored to produce individuals who were not only skilled and knowledgeable but also ideologically aligned and morally committed to the communist cause. This dual approach aimed at a comprehensive reconfiguration of the individual’s role in society, aligning personal aspirations with the collective goals of the state. The New Man, as envisaged by the Albanian communist leadership, was to be a product of this rigorous process of ideological conditioning and practical engagement in the service of the state.

The Cultural Revolution: Reshaping Social Norms

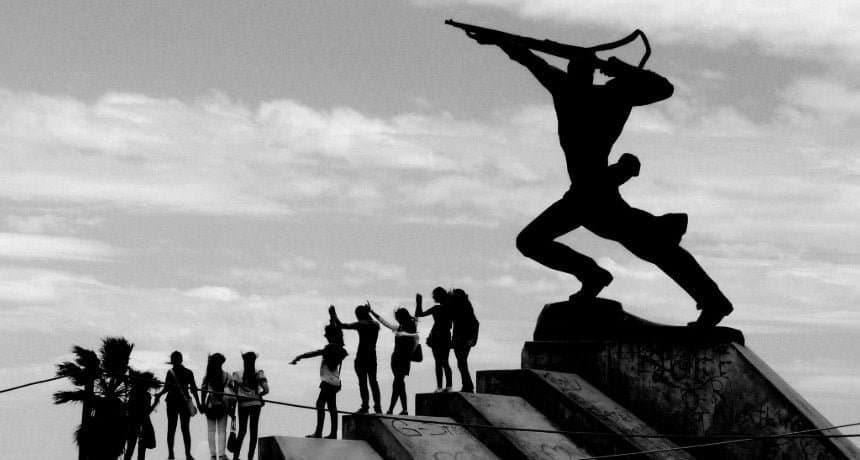

The Albanian Cultural Revolution (1961-1974) was an ambitious and all-encompassing endeavor that sought to reshape the very fabric of society in accordance with its vision of the New Man. This profound intervention touched upon every facet of life, ranging from birth to death, and was not limited to public spheres but extended deeply into the personal and intimate realms of individual existence.

Personal choices, which are often considered private and autonomous, were no exception. The regime sought to guide and often dictate these choices to ensure they were in harmony with communist ideals. This control included aspects like spirituality, marriage, parenting, and even day-to-day living, all orchestrated to reflect the state’s ideology.

Social customs, the backbone of cultural identity, underwent a radical transformation. Traditional and religious practices, rituals, and celebrations were either altered or completely replaced with new ones that better aligned with the principles of communism. The intention was to eradicate any elements of the past that were deemed incompatible with the socialist ethos.

Moreover, the intervention was palpable in the realm of aesthetics. The regime meticulously managed artistic expression, literature, music, and visual arts, ensuring that they not only complied with but actively promoted the communist ideology. This was not merely censorship but a redefinition of beauty and art through the lens of socialism.

Through these measures, the Albanian communist regime aimed to create a homogenous society where every aspect of life was imbued with the spirit of the New Man. This was a society where individual desires and preferences were subordinate to the collective will, and where personal identity was inextricably linked to ideological conformity. The Cultural Revolution was a bold attempt to construct a new social order based on the principles of Marxism-Leninism, fundamentally altering the way individuals perceived themselves and interacted with the world around them.

The New Aesthetics: Crafting the External Manifestation

The Albanian communist regime’s influence profoundly permeated the aesthetic realm, shaping not only the societal norms but also the physical appearance and cultural expressions of its citizens. This control over aesthetics was more than a mere imposition of conformity; it was perceived as an outward manifestation of the inner ideological commitment of the New Man.

Cultural expressions such as art, music, and literature were also rigorously controlled.

In this new aesthetic order, every element of personal appearance and cultural expression was meticulously curated to align with the state’s Marxist-Leninist ideology. Clothing, traditionally a medium of personal expression, was transformed into a uniform symbolizing equality and solidarity. The regime – more vigorously after 1967 and 1973 – prescribed what was appropriate to wear, often favoring simplistic and functional styles that negated any form of individualism or bourgeois extravagance.

Cultural expressions such as art, music, and literature were also rigorously controlled. The Party-State mandated that these forms of expression should not only comply with socialist realism but actively promote the principles of communism. Art became a tool for ideological indoctrination, with artists expected to produce works that glorified the proletariat, the revolution, and the achievements of the communist state.

The New Aesthetics was a deliberate strategy to embed the communist doctrine not just in the minds but also in the very appearance and surroundings of its citizens. This approach was emblematic of the regime’s deep conviction that external manifestations were as crucial as internal beliefs in realizing the vision of the New Man.

Onomastics and Identity: The Politics of Naming

The focus on naming was a deliberate political strategy, deeply embedded in the broader agenda of creating the New Man. Names, in this context, were more than personal identifiers; they were symbols of ideological allegiance and tools for reinforcing the regime’s vision that intertwined “albanianism” and communism. “Albanianism” dated back to the 19th century, at the beginning of the national-building process, and it was used in several ways from the 1920s in the sacralisation of politics in Albania, but the Party-State replaced nationalism with socialist patriotism and secularism with a rigorous state atheism.

The creation of the New Man was a comprehensive and transformative journey that redefined a nation.

The regime exerted influence over the naming of individuals, especially after 1967, steering away from names that carried religious connotations. This was part of a concerted effort to reject influences that were considered incompatible with the socialist ideals. Instead, names that were distinctly Albanian, reflecting the country’s “uncontaminated” culture, were encouraged. However, this albanisation politics didn’t prevent the import of personal names from other cultures (mostly Europeans).

By controlling the naming process, the regime sought to sever ties with the past, particularly with aspects that were deemed bourgeois and religious. Moreover, this focus on onomastics was also a means to embed the state’s ideology into the fabric of everyday life. Every time a person used their name or referred to others, they were, in effect, echoing the regime’s ideological principles. In this way, the politics of naming became a subtle yet pervasive method of indoctrination, constantly reinforcing the individual’s connection to the state and its ideals.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the New Man in Albania

The concept of the New Man in Albania transcended the realm of political rhetoric to become a profound and comprehensive attempt at societal transformation. This endeavor, deeply rooted in the Marxist-Leninist ideology of the communist regime, aimed to reshape not only the political landscape but also the fundamental identity and culture of the Albanian people.

The legacy of the New Man in Albania is multifaceted. On one hand, it reflects the regime’s success in instilling a collective consciousness aligned with its ideals, evident in the widespread acceptance and internalization of communist values among large segments of the population. On the other hand, it also highlights the deep and often coercive intrusion of the state into personal and cultural realms, raising questions about individual autonomy and freedom.

The cultural, social, and psychological imprint of this endeavor has continued to influence Albania long after the fall of the PLA regime. The reshaping of identities, the redefinition of cultural norms, and the alteration of social structures have left indelible marks on the nation. The legacy of the New Man is a testament to the power of ideology to shape society, for better or worse, and serves as a poignant reminder of the complex interplay between state power, individual identity, and societal change.

In conclusion, the creation of the New Man was a comprehensive and transformative journey that redefined a nation. Its legacy continues to be a subject of reflection and analysis, offering insights into the dynamics of societal change under authoritarian regimes and the enduring impact of ideological endeavors on national identity and culture.