The Enduring Legacy of Genocide and Persecution

In 2002, Samantha Power, later US ambassador to the United Nations, 2013-2017, declared that we were living in an “age of genocide.” Surveying the horrors of the preceding decade – Saddam Hussein’s use of chemical weapons against the Kurds in 1991; “ethnic cleansing” in the former Yugoslavia, 1991-2001; the 1994 genocide in Rwanda – she lamented the international failure to act upon the rhetoric of “never again.”

- The Enduring Legacy of Genocide and Persecution

- Historical Roots of Cultural Hatreds

- Political Economy and the Limits of Materialist Explanations

- The Illusion of Moral Progress

- Persecution in the Early Christian and Medieval Worlds

- From Persecuted to Persecutors: The Rise of Christian Hegemony

- From Religious Hatred to Racial Ideologies

- The Twentieth Century and the Systematization of Genocide

- The First World War and the Radicalization of Genocide

A quarter of a century on, and the atrocities have not ceased: Ukraine; the Israel-Hamas war; Xinjiang; Ethiopia; Sudan; Myanmar. The impotence of international humanitarian law in the face of these crises has now led some scholars, notably A. Dirk Moses, to critique the very notion of “genocide” as unfit for purpose: a flawed formulation that inaugurated a de facto hierarchy of crimes against humanity, creating a permissive environment for the implementation of lethal “permanent security” measures, falling outside the current definition of genocide.

Historical Roots of Cultural Hatreds

History has an important part to play in this debate, for the past exerts its grip upon the present. Cultural prejudices born in previous centuries drive cycles of persecution and genocide. Those German villages that burned their Jews as scapegoats for the Black Death, 1348-1350, showed a higher incidence of antisemitic violence and support for the Nazis in the 1920s and 1930s. In the modern United States, instances of racial violence linked to voter suppression in southern states are strongly correlated with the incidence of lynchings of African Americans, 1882-1930.

Accepting the flaws of the 1948 UN Convention on Genocide, such as its failure to protect political or social groups, or the leeway it allows states at war to inflict death and exile upon non-combatants, necessitates adopting a broader understanding of the phenomenon, as one form of persecution, aiming not at dominance over a group, but at its destruction.

Persecution itself has been a central theme of the western historiographical tradition, beginning with the martyrologies and early church histories of authors such as Eusebius (c.265-339 CE) which rooted Christian identity in the experience of successive persecutions.

Yet, notwithstanding its historical significance, persecution has been neither adequately theorised nor defined. It has been left to legal scholars, grappling with the stipulation concerning a “well-founded fear of persecution” in the 1951 UN convention on refugees, to debate the precise meaning of the word.

Jaakko Kuosmanen has offered the most useful definition: persecution may be understood as the simultaneous occurrence of three core components: “asymmetrical and systemic threat, severe and sustained harm, and unjust discriminatory targeting.” Such a definition would include genocide and thus allows for a sweeping history, from the amphitheatres to Auschwitz, that might illuminate more fully our own dilemma, as the legatees of two thousand years of persecution, seemingly trapped in this age of recurrent genocides.

Political Economy and the Limits of Materialist Explanations

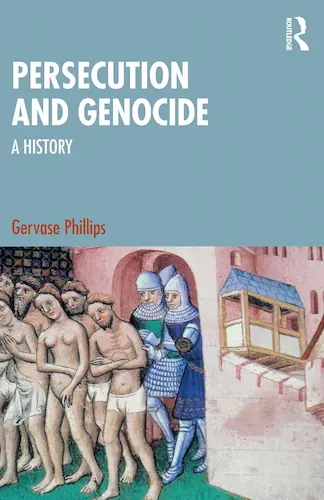

How do we explain persecution as a historical phenomenon? In an ambitious book, Noel D. Johnson and Mark Koyama have argued that religious persecution in medieval Europe was essentially a matter of “political economy.”

Weak states sought legitimacy through their relationship with religious authorities, demonstrating their sanctity, and thus right to rule, through the disciplining of those stigmatised for their purported deviance.

A more tolerant attitude towards religious minorities emerged only when wealthier and more centralised states emerged, with the fiscal capacity to enforce their rule, without the need to mobilise religious sentiment. For such a materialist analysis of persecution, Johnson and Koyama suggest that “ideas play a less crucial role” than the structural realities of economic and political transformations.

Yet by marginalising ideology, they sidestep the key questions necessary to understand specific instances of persecution: why, for example, did a long-established medieval scepticism towards the reality of maleficium (harmful magic) give way to a conviction of its terrifying reality in the fifteenth century?

Without such a shift in belief, the 60,000 victims of the witch-hunts would not have died. And, if the witch-hunts were driven primarily by the unthinking imperatives of “political economy”, why were 75% of those victims women? It is only by exploring beliefs, cultural prejudices, and often dynamic and volatile intellectual currents, that we have chance of answering such questions.

The Illusion of Moral Progress

Part of the challenge facing those with an interest in this difficult history is the lingering faith in humanity’s moral progress. The idea, expressed in the rhetoric of the Massachusetts abolitionist Theodore Parker (1810-1860), that the “moral arc” of the universe “bends towards justice,” still exerts a powerful hold. Yet, if that is so, how have we found ourselves in this bloody age of genocide?

If the universe has a “moral arc”, it is twisted and fractured, and all too often bent back on itself. The early modernist William Palmer has suggested a pattern of “moral regression”, where established legal, ethical, and customary protections for peoples’ lives have been ignored or abandoned.

The colonists deliberately created conditions in which epidemics struck with disproportionate lethality: enslavement, dispossession, disruption of food supplies.

Acknowledging such instances of moral regression allows us to navigate some of the more perplexing paradoxes encountered in the history of persecution: for instance, that just as slavery was being denounced as an unnatural condition for humanity and a cause of civil strife in sixteenth-century western Europe, the Atlantic slave trade was escalating, the enchaining of Africans justified by proto-racial notions of their inherently servile nature.

By employing Kuosmanen’s definition of persecution, equipped with a recognition of the centrality of ideologies to understanding its nature, and accepting the reality of recurrent moral regressions, it is possible to outline an epoch-spanning history of the phenomenon. Such a history must, perforce, be selective – its subject matter too ubiquitous and its geographical scope too daunting for a single volume. Yet proceeding by a series of chronological case studies it is possible to demonstrate the deep connectivity of hatreds ancient and modern, and the nexus of factors that have so distorted the “moral arc” of our universe.

Persecution in the Early Christian and Medieval Worlds

The early Christian Church was widely reviled, its adherents characterised as atheists, who denied the existence of the gods, who committed particularly shameful offences such as incest and cannibalism.

As such, they were occasionally scapegoated for misfortunes: fires and floods. The violence then unleashed upon them was localised, sporadic, driven more by the prejudices of the mob than the dictates of authority.

Yet the basic forbearance of the empire towards this superstitious cult shifted in the tumultuous third and fourth centuries CE. Under the emperors Decius (201-251 CE), Valerian (c.199-c.260), Diocletian (c.242-313 CE) and Galerius (c.268-311 CE), persecution became sustained and systemic.

Attempting to restore the peace of the gods, in an empire beset by economic and political turmoil, they legislated for the performance of ritual acts, including blood sacrifice, in which Christians could not participate. Christians were then pursued by the agents of the state, arrested, tortured, and executed, thus illustrating how shifting legal and social boundaries can transform mere prejudice into active persecution.

From Persecuted to Persecutors: The Rise of Christian Hegemony

When, benefitting first from the patronage of Emperor Constantine (272-337 CE), the Church itself rose to a position of hegemony, Christians’ commitment to peaceful conversion and rejection of religious coercion were sorely tested.

The Church itself forged a unified doctrine via theological debates that often descended into violence, with heretics and schismatics alike targeted. And the continued vitality of the various cultic practices dismissed as “paganism”, symbolised especially by the reign of Julian the Apostate (331-363 CE), seemed less a matter of regret, and more of a lingering threat. In some cities, such as Alexandria, the eclipse of paganism was hastened by riots, the desecration of temples, and the shedding of blood, most infamously that of the murdered philosopher Hypatia in 415 CE.

A seminal figure of this age was St Augustine (354-430 CE); he initially rejected compulsion in religion but his experiences of repentant Donatist heretics coerced back into his Church convinced him that “at times, then, one who suffers persecution is unjust, and one who persecutes is just.”

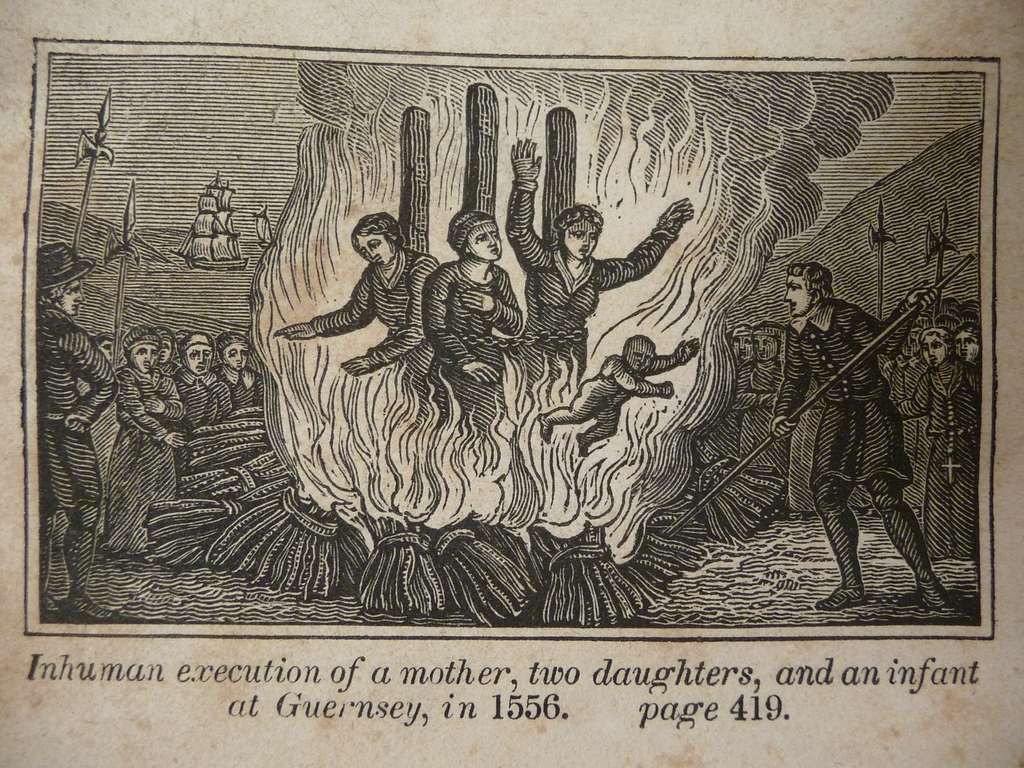

It is unfortunate that Augustine’s corollary admonishment that such disciplinary violence should be moderate in its implementation was less influential than his notion that persecution might be just. That influence was long felt – evident in the redemptive campaign of extermination waged against the Albigensians in Languedoc, 1209-1229, and the acts of the righteous persecutors and inquisitors who followed, pursuing heretics and witches to the stake.

From Religious Hatred to Racial Ideologies

It was evident, too, when the status of Europe’s Jews, long the only tolerated religious minority in Christendom, shifted portentously in the eleventh century. The popular religious fervour associated with the crusades saw mobs massacre Jewish communities, such as Emich of Flondheim’s assault on the Jews of Speyer in 1096. Grasping monarchs, such as Philip II Augustus in 1182, confiscated Jewish property and drove them into exile. The emerging intellectual denial of Jewish humanity by scholars such as Peter the Venerable (c.1092-1156) helped forge a stigma that still manifests in modern antisemitism.

Indeed, the modern legacies of medieval persecution of Jews was more far reaching than that. By the fifteenth century the status achieved by some Spanish conversos, Catholic converts from Judaism, attracted the ire of “old Christians.” They reconfigured Jewish religious identity into an inescapable biological essence and denied the redemptive power of baptism. Limpieza de sangre (purity of blood) statutes barred conversos and their descendants from many offices.

This powerful concept, by which pre-modern religious prejudices morphed into modern racism, was, thus, then available to legitimise the enslavement of Africans and the subjugation and dispossession of the indigenous peoples of the Americas, even those who converted to Christianity.

The mass deaths of indigenous peoples that accompanied such colonisation cannot be dismissed as an unfortunate corollary of their exposure to unfamiliar pathogens. The colonists deliberately created conditions in which epidemics struck with disproportionate lethality: enslavement, dispossession, disruption of food supplies. And they waged war with a ferocity unrestrained by the established constraints of “civilised warfare”.

The Twentieth Century and the Systematization of Genocide

By the turn of the twentieth century the institutional tools of genocide and an ideology of an exterminatory racism (determining not merely who should rule, but who should live) had emerged in Europe’s settler colonies: concentration camps, the unrestrained pursuit of “Total War”, the application of a brutal Social Darwinism as matter of policy, and the subsequent wholesale destruction of peoples, such as the Herero and Nama of Namibia, 1904-08.

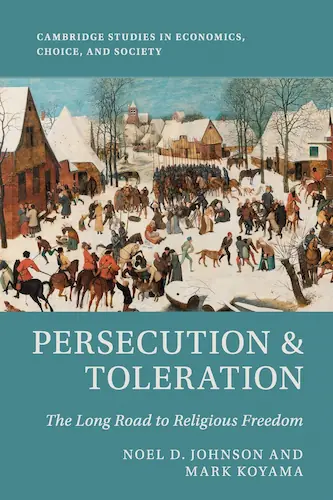

Such was one foundation of the modern age of genocide. Another was established on the Eurasian continent itself, at much the same time. It is most strikingly illustrated in the parallel histories of the empires of Russia (and its successor state, the Soviet Union) and the Ottomans.

The “dispeopling” (as contemporaries called it) of Caucasian Circassia in 1864 initiated a Russian practice of engineering loyal populations to match the empire’s expanding borders by deporting resistant or merely suspect groups, while inflicting upon them conditions calculated to “bring about [their] destruction, in whole or in part.” The policy reached its apex under Stalin, its victims including Ukrainians, Kalmyks, Chechens, Volga Germans and the Crimean Tartars.

The displacement of the Circassians and, later, Muslim refugees from the Balkan Wars, 1912-1913, into Anatolia roiled the politics of the Ottoman Empire. Old patterns of loyalty and tolerance crumbled, placing minority populations, especially Christian ones, at risk. Their aspirations for increased autonomy ran counter to the emerging ideology of Ittihadism (unionism), by which the “Young Turks” hope to transform the empire into a homogeneous, Islamic, and Turkish-speaking state.

The First World War and the Radicalization of Genocide

Further radicalised by the First World War, 1914-18, they too would violently re-engineer the demography of Anatolia to create a loyal population: Christian Armenians and Assyrians would be massacred, deported, starved. One million of the former and quarter of a million of the latter would die.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

The final stage of this process was the expulsion of 1.25 million Greeks from Anatolia, “exchanged” for 356,000 Turks driven from Greece. The Christian population of Anatolia had fallen from 20% to 2%. The borders so created were effectively legitimised by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which accepted “population transfer” as a solution to “the minorities problem,” and abandoned efforts to bring to justice those who had committed crimes against humanity. Thus was the way paved for further genocides.

In 1939, Hitler would ask “Who still talks nowadays about the extermination of the Armenians?” as he embarked upon a murderous re-ordering of eastern Europe’s demography. Under the radicalising pressures of war, that project would become ever more pitiless, reaching its barbarous crescendo in the Holocaust: “the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe.” By then, the age of genocide was truly upon us.