The Unique Role of Primary Elections in American Democracy

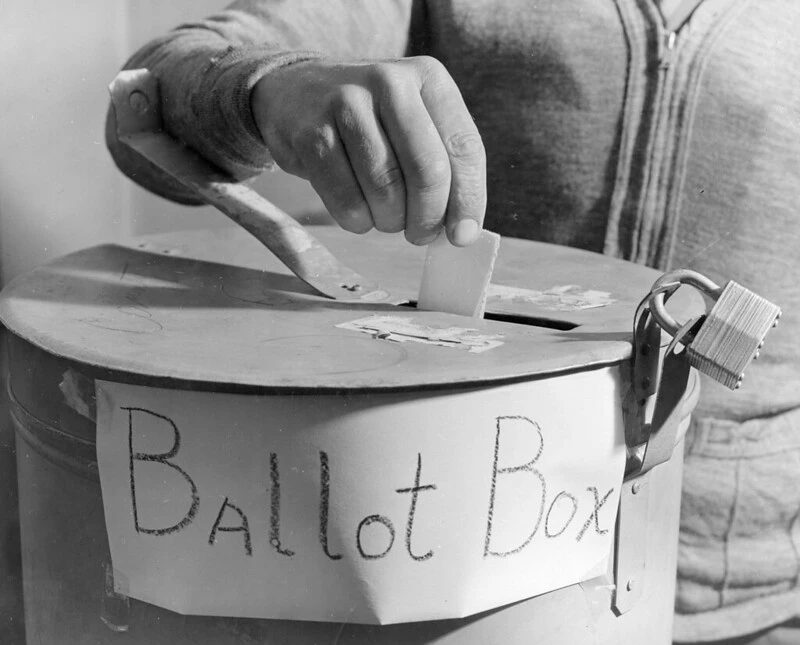

A growing number of democracies allow registered party members some say in choosing party leaders or legislative candidates, but the United States is unique in its use of primary elections for virtually all elected offices.

- The Unique Role of Primary Elections in American Democracy

- The Impact of Primary Elections on Political Polarization

- An Overlooked Period of Primary Election Reforms (1928-1970)

- The Reassertion of Party Control: Fact or Fiction?

- Theories on the Evolution of Primary Election Laws

- Outside Group Capture of the Primary Process

- Bad Primary Laws

- The Role of Partisanship in Shaping Primary Laws

- Why the History of Primary Election Reforms Matters Today

- Lessons from History for Contemporary Reformers

- Rethinking Electoral Reforms: Beyond Primaries

Primary laws vary significantly across the American states, however, in many aspects, including the ease of registering to vote in a party’s primary and the ability of parties to make rules about how easy it is to appear on the ballot. Surveys show that most Americans view primary elections as an essential feature of democracy, and that they support reforms aimed at increasing voter engagement in primaries and reducing party control over these elections.

Few would dispute the notion that the two major American political parties are more polarized today than ever before.

At the same time, barely one-fifth of eligible citizens vote in primaries, and the winners of primary often take positions that are not supported by the majority of eligible voters.

The Impact of Primary Elections on Political Polarization

Politicians tend to be more sanguine about primaries, however. Every election cycle, primaries produce at least one or two surprising results – a veteran lawmaker is upset in a low-turnout primary by a political newcomer; a fringe candidate wins a seven- or eight-candidate primary with a quarter or less of the vote; or a wealthy interest group pours millions of dollars into a House primary in order to send a message about its clout.

In New York and Indiana, fixable problems with primary laws led the states to abandon the primary for decades.

Although the vast majority of incumbent politicians win their primaries easily, the seeming randomness of such results can lead politicians to err on the side of caution, to avoid breaking with their party on high-profile issues. Primaries are, according to many analysts, a major source of political polarization.

Few would dispute the notion that the two major American political parties are more polarized today than ever before. But are primaries the cause of this problem? There are many reasons to say yes, and in recent years many suggestions have been offered about how to reform primaries – open them up to all voters, adopt ranked-choice voting, allow parties to limit the number of candidates who run, or perhaps do away with primaries altogether.

However, primaries have been with us for over a century. In the decade preceding the First World War they were adopted for most offices in all but three states, and the remaining three stragglers adopted them by the 1950s. It is hard to blame a reform that has existed for over a century for problems that have only become evident in the past twenty years.

An Overlooked Period of Primary Election Reforms (1928-1970)

In my recent book Reform and Retrenchment: A Century of Efforts to Fix Primary Elections I approach this problem from two different angles. First, the book offers a history of primary election reforms from 1928 to 1970. Second, I build upon this history to argue that most primary election reforms that have been proposed are unlikely to have a measurable effect on political polarization.

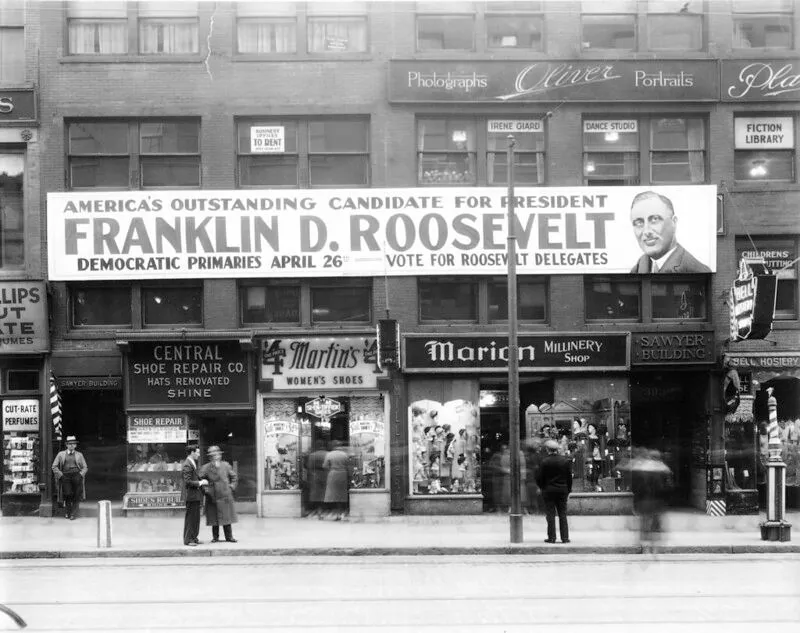

The reason why I focus on the period from 1928 to 1970 is simple – no one has ever written a history of primary election law changes during this time period, and it is a crucial one for understanding American elections. The direct primary (not to be confused with delegate selection primaries, such as are used to select presidential nominees) was hailed as one of the most successful Progressive Era reforms, and its proponents promised that it would reduce the power of corrupt party bosses and empower regular voters. In the years following the introduction of primary elections, there were dozens of articles on them published in scholarly journals.

The book offers a historical account of every major state-level change to primary laws, along with an analysis of whether each change was expansive or restrictive.

Professor Charles Merriam wrote a landmark book in 1908 summarizing what was known about primaries, and in 1928 he and coauthor Louise Overacker wrote a revised edition. After 1928, however, political scientists lost interest in the direct primary. What little was written about primaries appeared in regional political histories.

In the 1970s, the Democratic Party’s McGovern-Fraser reforms sought to standardize state primary laws, and over the subsequent decades scholarship on primaries, and scholarship on primaries again began to increase. Yet the time period from 1928 to 1970 remains opaque. The conventional wisdom by the 1950s was the political parties had reasserted control over primary elections – after a tumultuous few years of adjustment, primaries had ultimately failed to dislodge the parties.

The Reassertion of Party Control: Fact or Fiction?

If parties did re-establish control, however, we should see changes in state laws that rein in some of the unpredictability of primaries, or we should see efforts to give parties greater control over nominations.

Hence, this book focuses upon cataloguing changes in primary election laws over this important period in which the public was not paying attention, and parties did, perhaps, have the opportunity to reassert themselves.

The book offers a historical account of every major state-level change to primary laws, along with an analysis of whether each change was expansive (that is, reduced party power and enhanced the role of voters in the candidate selection process) or restrictive (that is, increased party control and reduced public participation).

The pattern that emerges suggests that the claim about retrenchment was not borne out – this was in fact an era of surprising variation in primary laws. States tinkered with primaries for many reasons, and many of the ideas in vogue today were attempted during this era.

Theories on the Evolution of Primary Election Laws

In the book I offer four different theories about changes in primary election laws. First, I explore claims that the Progressives simply lost interest. Progressive Era reformers championed a range of political reforms aimed at limiting political corruption, reducing the power of political bosses, and increasing citizen participation in politics. It is generally understood that the Progressive Era ended in the 1920s.

I show that we should be suspicious of legislative calls for changing primary laws.

The major progressive intellectuals became disenchanted with some of their reforms, some moved into the Democratic Party, some passed away, some became opponents of the movement. The problem with this argument is that the primary was never really a Progressive reform, so Progressive did little to defend it.

Some Progressives were happy to take credit for the direct primary because it represented an easy win, but with the exception of a handful of midwestern governors, most Progressives were suspicious of the primary precisely because it maintained a strong role for the parties. In states with a strong Progressive movement, however, the primary did become entrenched, and in some Progressive-adjacent states, such as Rhode Island and Connecticut, the direct primary did subsequently gain traction among liberals. Even as Progressivism disappeared, the primary still sounded progressive to voters.

Outside Group Capture of the Primary Process

A second theory is that there was a backlash against the capture of primaries by outside groups. The most successful of these was the Nonpartisan League (NPL), an agrarian socialist organization centered in North Dakota during the 1910s and financed through member dues.

The NPL ran candidates in many Republican primaries in the state, not because it was sympathetic to Republicans but because it correctly guessed that it would be easier for its candidates to win elections as Republicans in most parts of the state than as Democrats; in the small number of districts where most voters were Democrats, it ran candidates in the Democratic primary.

History tells us that when politicians try to change election rules, they are seeking to do so in a way that benefits them.

Although NPL control of North Dakota politics was short-lived, parties in many Midwestern and Plains states sought to change their primary laws to block the NPL. These manipulations took different forms, however, depending on whether the parties were trying to block the NPL from power or dislodge it.

Voters in many of these states had, however, gotten used to primaries and had accepted the contention that primaries were a more democratic way to select candidates; every time a state tried to pass restrictive laws, the voters rebelled and put the more open laws back. Although the nation has yet to see another similarly successful hostile takeover of primaries, one important lesson here is that voters will always opt for the option that sounds more “democratic.”

Bad Primary Laws

Third, many primary laws were simply bad laws, and some of the original ideas of reform advocates yielded results contrary to what reformers (or voters) had anticipated. In New York, all parties (including minor ones) were required to hold primaries; hence, the ballot was several feet long and polling stations ran out of paper. In South Dakota, the “Richards Primary” required parties to put their platforms up to a vote and required an unwieldy number of debates within each of the state’s counties.

The lesson here is that it is hard to figure out whether efforts to “fix” primary laws are sincere, or malicious. This is a common paradigm in the comparative literature on political reform; one contemporary American analogue is the Affordable Care Act, the 2010 bill to expand health insurance.

Once a law is passed, it can become difficult to make necessary modifications to it because many of the loudest voices preaching for changing it are the people who never wanted it to work in the first place, and many reform proposals that are offered by opponents are not efforts to make the law work better but efforts to undermine it entirely or make it so unworkable that it will need to be repealed. In New York and Indiana, fixable problems with primary laws led the states to abandon the primary for decades.

The Role of Partisanship in Shaping Primary Laws

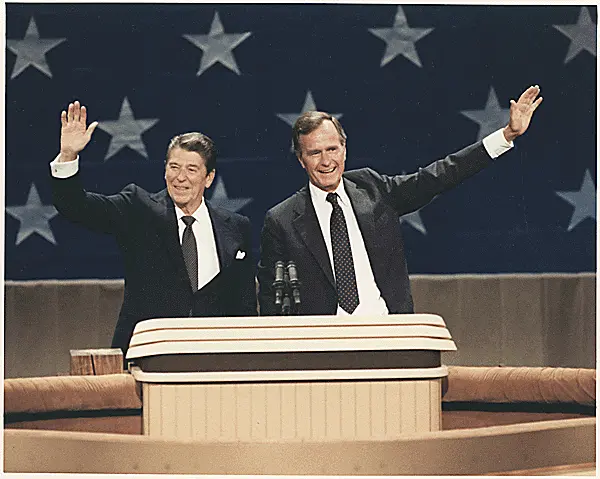

And fourth, I show that we should be suspicious of legislative calls for changing primary laws. Governing parties always want to amend primaries in ways that they think will maintain the status quo, while parties out of power want to change the laws in ways that will enable them to gain power.

During the 1928 to 1970 period, the most substantial changes to primary laws took place at moments when the balance of power in state legislatures is close. In the case of two late adopters of the primary, Rhode Island and Connecticut, the direct primary was introduced, albeit in restrictive form, following a change in control of the state legislature and the governorship.

In both states, Democrats adopted the direct primary largely because they thought they would benefit from it. Similarly, California Republicans had held power up until 1958 largely because of a law allowing candidates to “crossfile” to run in both parties’ primaries. After Democrats gained control of the legislature, they promptly abolished this law. As in many studies of comparative politics, parties will frame proposals that are to their advantage as “democratic” or good government reforms.

Why the History of Primary Election Reforms Matters Today

This history shows that, far from being an era of quiescence or retrenchment, the middle years of the twentieth century were in fact a period of tumult in the nation’s candidate selection procedures. The irony of this history is that most primary reforms have minimal effects. Popular stories about primaries take hold – open primaries help liberals, for instance – and parties fight over reforms that make only slight differences.

These simplified assertions are still evident today. When I turn my attention to contemporary politics, I begin by exploring proposed primary reform legislation in state legislatures since 2000 (that is, while the historical account looks only at successful legislation, here I look at proposed legislation). In each election cycle, an average of fifty significant pieces of legislation regarding primaries has been introduced; over these twenty years, primary reform legislation has been introduced in 45 states.

Most of these proposals are based on folk theories from the early twentieth century about enhancing democracy and voter choice. In some cases, the logic of these theories is just wrong, while in others it’s somebody’s idiosyncratic pet project, or a veiled effort to help one person or party’s campaign.

Lessons from History for Contemporary Reformers

Apart from being alert to the four broad patterns outlined above, what might contemporary scholars and reform advocates learn from this history? First, we should learn from the past. We should be skeptical of politicians’ motives; history tells us that when politicians try to change election rules, they are seeking to do so in a way that benefits them.

We should be careful not to overpromise; most reform efforts have yielded minimal results, either because parties adapt or because the proposed reforms were never likely to yield dramatic changes. As Bruce Cain has noted, a challenge for reform advocates is that they must simultaneously persuade activists that the reform will be worth the effort they contribute, while simultaneously seeking to convince opponents that the reform will not harm them. The history I offer in the book suggests, furthermore, that we should not assume that reforms which have been tried in the past are likely to have a major impact today.

Second, it is necessary to understand regional context. Political parties developed in very different ways in the different American states. Although regional variation in political culture is not as evident today as it was fifty or a hundred years ago, party systems at the state level are sufficiently different that a reform which makes sense in one state may not work in another. Many recently implemented primary reforms, such as the top 2 nonpartisan primary in California and Washington or the top 4 / ranked choice voting system adopted in 2022 in Alaska, have reduced polarization somewhat in these states.

The political culture of these states may have influenced whether reforms were adopted and whether they succeeded, however; it is too early to tell whether the results here are applicable to states with stronger, more entrenched political parties. Just as there is no one story about the direct primary that explains all states, so there is unlikely to be one reform that makes sense across all states.

Rethinking Electoral Reforms: Beyond Primaries

Third, it is possible that those who would reform American elections would be better off focusing their attention elsewhere. It may well be that problems in contemporary primaries are not problems with the system, but with the nation’s campaign finance laws, with changes in media and social media, or with particular party leaders.

Given the messy history of primary election law changes and the lack of a national solution to what is, in the end, a problem most evident in national politics, perhaps we should worry about other reforms. There is perhaps a statute of limitations – if the primary mostly worked ok for most of the twentieth century, and if people like it anyway, then maybe it is futile to argue against it, or at least we should wait a little while longer before concluding that candidate selection procedures which functioned adequately for over a century should be abandoned based on two decades of troubling results.

Or, fourth, it is possible that the right approach is to think big – to look at the history of primary elections and figure out what has not been attempted before. Perhaps the newly adopted election system in Alaska is different enough from what has been tried elsewhere, and we should not be so pessimistic as to conclude that no reform will succeed just because of the history I have outlined here.

Similarly, I argue in another forthcoming book that adopting a one-day national congressional primary could boost voter turnout far more than have any of the past reforms described here, and that a radical increase in voter turnout might lead to a far more representative primary electorate than we have ever seen. Perhaps other novel reform proposals, as well, are yet to come.

If nothing else, the research here shows that it is not possible to understand primaries if one only looks at the past twenty years – or even the period from 1970 on that I discussed in my first primaries book. In addition, it is also difficult to understand primaries if one relies on the early twentieth century accounts of what primaries were intended to do. To get the full picture, it is necessary to fill in the gap between those two eras.