In June 2022, the United States Supreme Court snatched back fifty years of constitutional abortion rights from people living in the United States. With three new Donald Trump appointments joining three longer-term Republican appointments on the court, a 6-3 supermajority reversed Roe v. Wade, leaving women and girls with no federally guaranteed right to access abortion.

That shocking decision, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, left Americans totally unprotected from gerrymandered legislatures in southern and midwestern states stripping them of bodily autonomy and liberty to access basic medical care. After Dobbs, many states banned abortion outright or severely restricted access, even in cases of miscarriage or complications later in pregnancy. Reports soon emerged that women were dying in Georgia, Texas and Indiana.

This book reveals the bold and creative work by reproductive health advocates to free abortion pills from the control of politicians and the medical system.

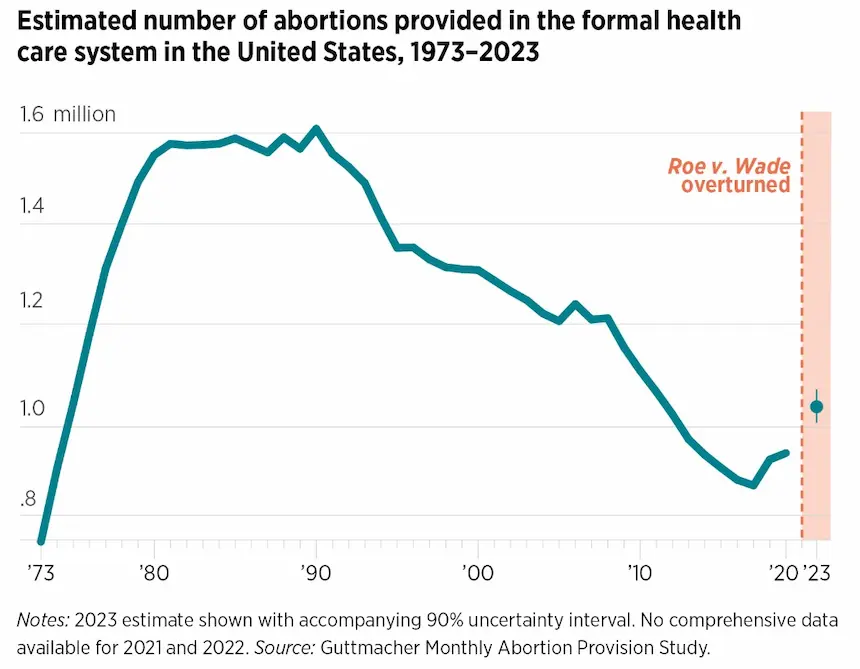

Despite the changed legal landscape, abortions in the United States actually increased after Dobbs, climbing above one million in 2023 for the first time in a decade. The number of abortions had peaked at 1.6 million in the early 1990s, before dropping precipitously after the Supreme Court opened the door to increased regulation of abortion with their 1992 decision in Casey v. Planned Parenthood.

In the years following, many states imposed burdensome restrictions, such as waiting periods and limitations on who could provide abortions and how. By the time Trump took office in 2017, abortions had dropped by almost half—to around 850,000. But then this number began to rise after the election of Donald Trump.

Why are abortions climbing, just as many states are banning it? My new book, Abortion Pills: US History and Politics, explains this paradox. The simple answer is: abortion pills and telehealth. Abortion pills include two medications: mifepristone, which blocks the effects of the pregnancy-sustaining hormone progesterone, and misoprostol, which causes uterine contractions. Researchers in France developed mifepristone in the 1970s. Women in Brazil discovered the use of the ulcer medication misoprostol for abortion in the 1980s, now used in combination with mifepristone or alone for abortion.

After intense political conflicts, the FDA approved mifepristone for use in the United States in 2000, but women had to wait another two decades before the medication became widely accessible via telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic and through underground networks post-Dobbs. Based on over 80 interviews, this book reveals the bold and creative work by reproductive health advocates to free abortion pills from the control of politicians and the medical system, and place these medications in women’s hands.

The Fight to Bring Abortion Pills to the US

The story begins with the development of RU 486—later known as mifepristone—by the French company Roussel Uclaf in the 1970s. Patented as “RU 486” in 1980, mifepristone was approved by the French government in 1988. But due to anti-abortion political pressure and threats of violence, Roussel Uclaf declined to market the medication to the United States. Reproductive health advocates responded by organizing a campaign to pressure the company to reverse course.

They collected 700,000 petitions and organized a delegation of feminist leaders, medical professionals, and prominent scientists to deliver the petitions to the Paris headquarters of Roussel Uclaf in France and to its parent company Hoechst AG in Germany. Despite this pressure, the companies refused to market the medication in the United States because of the hostile political climate in the country, including an import ban on RU 486 imposed by the Bush administration in 1989.

The election of President Bill Clinton in 1992 brought a much more favorable political climate for abortion. Nevertheless, it took another eight years for the FDA to approve mifepristone. After threatened boycotts from anti-abortion groups, large drug companies declined to develop the medication for the U.S. market. In 1995, due to the efforts of reproductive rights advocates and the Clinton administration, Roussel Uclaf donated all rights for medical uses of mifepristone in the United States to the nonprofit organization Population Council.

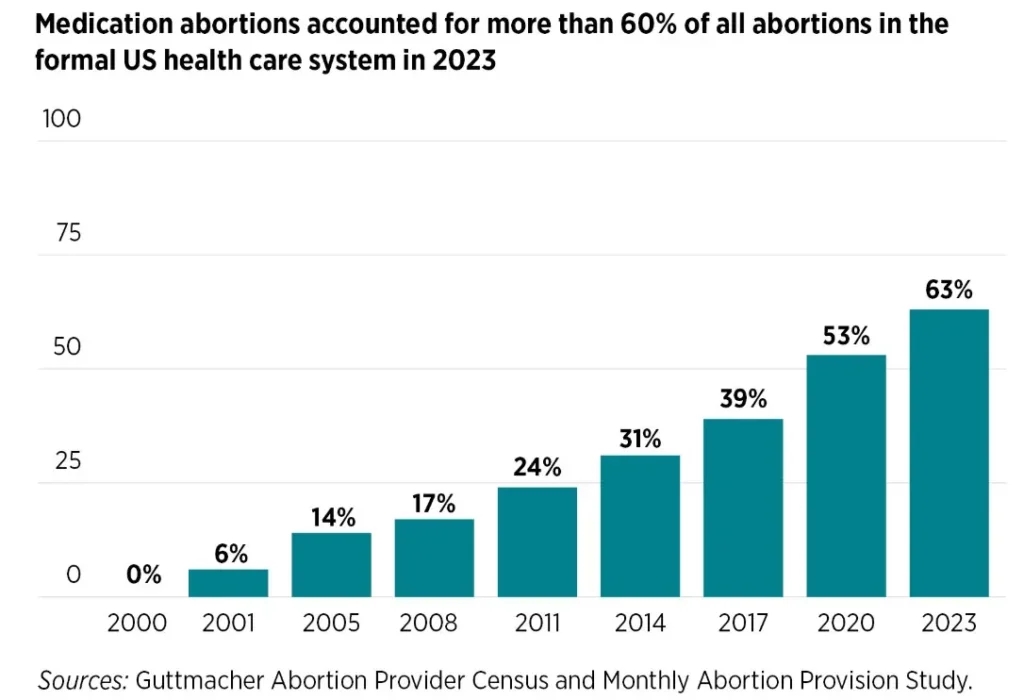

In 2017, medication abortion accounted for approximately 40 percent of all recorded abortions.

The Population Council conducted clinical trials, applied for FDA approval and sought a drug company to distribute the medication in the United States. The Population Council eventually granted the rights to distribute mifepristone to Danco Laboratories, a small private company specifically formed for this purpose.

After a long fight by anti-abortion activists to block the drug from the U.S. market, the Clinton administration’s FDA finally approved mifepristone for use within the United States in 2000. Yet due to anti-abortion political pressure, and despite the medication’s strong safety record, the FDA tightly restricted mifepristone, allowing only doctors registered with the Danco to dispense the medication.

In a highly unusual move, the FDA required doctors to stock and dispense the medication themselves in person to patients. In addition, the FDA only allowed use of the drug through seven weeks of pregnancy. The FDA later placed mifepristone in a highly restrictive drug safety program called the Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS).

The Fight to Increase Access

Many people hoped and predicted that mifepristone would transform abortion health care. A 1993 Time magazine cover proclaimed, “The Pill that Changes Everything.” In 1999, the New York Times article called mifepristone “the little white bombshell.” Reproductive rights advocates worked hard to convince obstetricians and gynecologists as well as primary care providers to offer medication abortion services.

However, few clinicians outside of abortion clinics would prescribe abortion pills because of the burdensome FDA restrictions and fear of anti-abortion harassment and violence. In 2011—over ten years after FDA approval—only one percent of abortions were done outside of abortion clinics and hospitals. Reproductive rights advocates nevertheless continued working to remove clinical and legal barriers to medication abortion, but it took years to finally loosen some of these restrictions.

Key to increased access were researchers who conducted studies showing that mifepristone was safe and effective at a lower dose and later in pregnancy. Using this research, reproductive health advocates called on the FDA to remove some of the restrictions on mifepristone.

In 2016, during the final days of the Obama administration, the FDA finally modified the medical protocol for mifepristone provision to make the medication easier to use and more accessible, including lowering the dosage and extending the period for use of the medications to ten weeks. The FDA also allowed a wider range of licensed healthcare providers to prescribe mifepristone and required fewer office visits to get the medication.

The FDA in 2016 also granted an exception to the in-person distribution requirement of the REMS for a research study called TelAbortion by Gynuity Health Projects, allowing physicians in the study to prescribe abortion pills through telehealth and mailing pills. As a result of these changes, the percentage of medication abortion increased significantly. In 2017, medication abortion accounted for approximately 40 percent of all recorded abortions. This share rose to 54 percent in 2020 and 63 percent by 2023.

But increasing state-level abortion restrictions during the Obama years, and decreasing access to abortion health care, made advocates realize that they had to do more. They began meeting to discuss abortion outside of the medical system, including use of misoprostol alone, drawing on women’s knowledge and practice across the globe. This work accelerated after Donald Trump was elected president in November 2015, with promises to appoint anti-abortion Supreme Court justices.

Dawn of Telehealth Abortion

After the 2015 election, the organization Plan C launched a website to share information about self-managed abortion, including how to obtain abortion pills online and use them safely at home. Another organization, “Self-Managed Abortion. Safe and Supported” (SASS) launched a similar website in early 2018.

The same year, Plan C persuaded Dutch physician Rebecca Gomperts to form a new organization called Aid Access, based in Austria, which began offering abortion pills by telehealth to people in all 50 states for a sliding scale fee. Activists became more determined when Trump nominated Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court in the fall of 2018. Senate confirmation of Kavanaugh created an anti-abortion majority on the Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, researchers at Gynuity and Advancing New Standards in Reproductive Health (ANSIRH) at University of California at San Francisco advanced an aggressive research agenda to support removing all FDA restrictions on mifepristone. In addition, to make mifepristone more affordable, advocates encouraged the development of a new company, GenBioPro, to make generic mifepristone, which the FDA approved in 2019. But anti-abortion advocates pushed back against increased medication abortion access by fighting for restrictions at the state level, including bans on mailing of abortion pills. By 2020, 19 states had adopted laws requiring in-person dispensing of abortion medications.

A major turning point in abortion pill access in the US occurred after the COVID-19 pandemic hit in March of 2020. Many healthcare services became available via telehealth, delivered remotely by videoconference, telephone or online forms. Under the Trump administration, the FDA lifted in-person distribution requirements on most drugs to increase telehealth access, but they kept this restriction on mifepristone in place.

Healthcare providers, medical researchers and reproductive rights advocates pressed the FDA to lift this restriction, submitting new evidence on the safety and efficacy of telehealth abortion based on the TelAbortion research.

On March 30, 2020, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists issued guidance stating that clinicians could perform an assessment, counseling and consent for medication abortion by video or telephone and that an ultrasound and other in-person tests were not necessary in most cases.

Yet the FDA refused to change their policy, so medical providers and reproductive rights advocates sued, arguing that the restriction subjected patients to unnecessary risks of contracting COVID-19 as a condition of receiving the medication.

In July of 2020, a Maryland federal court suspended the FDA requirement that patients make in-person visits to medical providers to obtain abortion pills, ruling that the requirement imposed a “substantial obstacle” to abortion health care that was likely unconstitutional. Plan C quickly began recruiting clinicians to offer telehealth abortion. In the following months, telehealth abortion startups began opening up across the country, such as Just the Pill in Minnesota and Choix in California.

A key development facilitating access to telehealth abortion was the opening of an online pharmacy called Honeybee Health in the fall of 2020. Honeybee, based in California, began selling generic versions of the abortion pills at steep discounts, without the need for insurance. Later, American Mail Order Pharmacy began offering name-brand abortion pills. New online abortion clinics offered medication abortion for significantly less money than brick-and-mortar clinics—as low as $150 versus the average clinic-based cost of $550. Many telehealth providers also had sliding scale fees.

The Trump administration appealed the Maryland court ruling, which the Supreme Court overturned in January of 2021, days before Biden took office. Biden promptly directed the FDA to reconsider the in-person distribution requirement, which they lifted for the duration of the public health emergency in April 2021. Then in May, President Biden ordered the FDA to consider permanently lifting the requirement.

Researchers studied the experiences of patients of the early telehealth abortion providers, finding that telehealth abortion was just as safe as in-clinic abortion and patients liked the service. Advocates submitted this research to the FDA, hoping they would permanently lift the in-person dispensing requirement and allow providers to offer telehealth abortion beyond the pandemic.

Expanding Abortion Pill Access

Despite the increased access to medication abortion via telehealth, reproductive health advocates saw the writing on the wall with the conservative supermajority on the Supreme Court: Roe would likely be overturned. Plan C expanded information on their website about options for obtaining abortion pills, including mail forwarding with U.S.-based telehealth providers and reliable online sellers of abortion pills, which were vetted by Plan C researchers. Clinician advocates formed the Miscarriage and Abortion Hotline to confidentially assist people using abortion pills outside of the medical system.

Meanwhile, legal advocates formed the Repro Legal Hotline to provide legal support to people self-managing abortion and the Repro Legal Defense Fund to help cover legal expenses for people investigated or criminally charged for self-managing abortion. Reprocare formed to provide logical and emotional support to people seeking abortion pills and using them outside of the formal medical system. In May 2021, Texas passed SB 8 banning abortion at six weeks with a civil enforcement mechanism. When the Supreme Court allowed the law to go into effect in September 2021, demand for abortion pills outside of the medical system surged and activists redoubled their efforts to meet this need.

In April 2022, a Texas prosecutor improperly charged a women alleged to have used abortion pills with murder.

In December 2021, the FDA permanently lifting the in-person distribution requirement. As a result, telehealth abortion services proliferated across the country and eventually became available in about half of the states. The FDA decision spurred the formation of new telehealth abortion clinics, but 19 states still had laws prohibiting telehealth abortion, in direct contradiction to the FDA rule.

The FDA also announced that they would permit brick and mortar pharmacies to dispense mifepristone for the first time, although they required these pharmacies to be certified to the frustration of abortion pill advocates. As Texans traveled northward and westward to states with legal abortion, telehealth abortion played an important role in helping to meet demand, serving as proof of concept for a post-Roe future.

When the Supreme Court overturned Roe on June 24, 2022, traffic exploded on the websites of Aid Access, Plan C, SASS and other abortion pill groups. New community groups sprung up, such as Red States Access and We Save Us, that obtained abortion pills from outside the United States and mailed them for free to people in states banning abortion.

A Mexico-based network of abortion pill activists called Las Libres began offering free abortion pills to people living in states with bans and helped Americans create their own Las Libres network, focused on serving Spanish speaking communities in the United States.

Meanwhile, states allowing abortion passed shield laws to protect clinicians providing abortion health care to people coming from states with bans. Some advocates pushed states to pass shield laws protecting telehealth abortion as well. Massachusetts passed the first telehealth shield law in July of 2022 and then Washington state passed a similar law in April 2023. Six other states soon followed and clinicians located in these states began providing telehealth abortion services to people living in states with bans.

By the first quarter of 2024, 20 percent of all abortions would be done by telehealth, and tens of thousands of women living in states banning abortion would gain access to abortion pills from shield state providers. Many more obtained abortion pills through community networks and online sellers of abortion pills vetted by Plan C. An abortion subreddit run by the Online Abortion Resource Squad became an increasingly popular place where people shared information and support for self-managed abortion.

In response, anti-abortion advocates targeted women using abortion pills. State abortion bans criminalized medical providers, but the women who had abortions. So anti-abortion advocates began calling for state legislators to pass laws criminalizing the use of abortion pills. In April 2022, a Texas prosecutor improperly charged a women alleged to have used abortion pills with murder. In February of 2023, an abusive husband in Texas used SB 8 to sue his estranged wife’s friends after they helped her obtain abortion pills.

Both cases were later dropped. In 2024, Louisiana designated abortion pills as controlled substances, and Texas and North Carolina legislators introduced laws to prohibit people from sharing information about abortion pills, in clear violation of the First Amendment. The anti-abortion movement also spread disinformation about the safety of abortion pills and advocated dangerous “abortion pill reversal” theories through “crisis pregnancy centers,” which pretended to be abortion clinics in order to interfere with access to abortion.

I was inspired to write this book after anti-abortion advocates filed a lawsuit in Texas in November 2022, alleging that abortion pills were dangerous and the FDA had rushed through approval of the mifepristone. Having covered abortion pills since 2018, I knew this was not the case, but could find no scholarly books on abortion pill history and politics. The Texas lawsuit sought to invalidate the 2000 FDA approval of the mifepristone and misuse a nineteenth-century anti-obscenity law to ban mailing abortion pills nationwide.

Meanwhile, abortion pill advocates filed a lawsuit demanding the FDA remove the remaining restrictions on abortion pills and then filed two more lawsuits challenging state restrictions on abortion pills, arguing they were preempted by federal law. In June 2024, the Supreme Court dismissed the Texas lawsuit against the FDA for lack of standing, but three states intervened to revive the lawsuit.

As Trump heads into a second term, threatening further restrictions on abortion, advocates are poised to continue the fight to expand abortion pills outside of the legal and medical systems if need be. My book offers important historical and political context for understanding these developments and fighting back against misinformation about the history of abortion pills.