The past few decades have seen significant shifts in climate activism and environmental rights advocacy around the world. New climate action organizations have formed across the globe and have rapidly expanded their followers and ‘repertoires of collective action.’

- The Rise of Global Climate Activism: New Movements and Strategies

- The Digital Revolution in Climate Activism: Technologies and Global Impact

- More of the Same, Just Faster? Or Transformative Impact?

- Transforming Activism: Digital Tools and New Strategies

- The Dark Side of Digitalization

- The Risks of Digital Activism: Surveillance, Disinformation, and Exclusion

- Tech’s Dirty Secret

- The Double-Edged Sword of Digital Technology in Climate Advocacy

The past ten years have seen the rise of groups like Fridays for Future, the American Sunrise Movement, Last Generation, Just Stop Oil, and Extinction Rebellion, that mobilize predominantly younger people to take to the streets and engage in protest or direct action.

Non-governmental organizations and private citizens are suing governments and corporations for their inaction, or direct contributions, to climate change.

We have also seen the emergence of powerful groups of older citizens, such as Bill McKibben’s Third Act, a community of Americans over sixty who campaign for climate action, and KlimaSeniorinnen, a Swiss association of more than 2,500 women aged 64+ who successfully sued the Swiss Government before the European Court of Human Rights for failing to adequately address climate change.

The Rise of Global Climate Activism: New Movements and Strategies

With the proliferation of new climate organizations and climate movements have come a broadening of ‘theories of change’. While activists continue to lobby decision-makers for political change and pursue traditional strategies of street protest, sabotage, and blockades, more and more climate activism takes place before national and international courts where non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and private citizens are suing governments and corporations for their inaction, or direct contributions, to climate change.

Digital advocacy is spreading fast among environmental groups in the Global South.

Climate litigation has grown from a handful of cases globally in the early 2000s to between 250 and 300 new cases annually in recent years. While governments and local authorities continue to be the main targets of climate litigation, private companies are also increasingly in the firing line, being sued for direct environmental harms through ‘polluter pays’ style lawsuits or for ‘climate-washing.’

Whether on the streets or in the courtroom, today’s climate activism often moves quickly from the local level to reach global audiences and policymakers. Consider that what started as a protest by a lone high school student, Greta Thunberg, outside the Swedish parliament in September 2018 brought an estimated 7.3 million to the streets across 183 countries by September 2019 in what was dubbed the world’s first global climate protest. Or take the example of Pacific Island Students Fighting Climate Change who successfully lobbied a majority of countries at the UN General Assembly to request an Advisory Opinion from the International Court of Justice on state obligations under the Paris Agreement.

Underlying these recent developments are fast-paced changes in the digital environments climate activist organizations operate in. Empowered by new social media technologies, big data, AI, satellite imagery, and more, activists across the world are experimenting with new forms of organization and new strategies to promote climate action. Many climate groups today use digital platforms to fundraise, attract followers, organize actions, and form strategic alliances with likeminded groups.

For example, digital advocacy organizations like Fridays for Future, 350.org, Campact, and GetUp! have used social media platforms to mobilize millions of people in support of climate action. Other groups have relied on digital technologies to collect, process, and analyse vast amounts of data, which they use to lobby policymakers, monitor companies’ GHG emissions, and to investigate and prosecute environmental crimes.

The Digital Revolution in Climate Activism: Technologies and Global Impact

In our recent book, Climate Activism, Digital Technologies, and Organisational Change, we examine how digital technologies have amplified or transformed climate activism in different parts of the world.

So far, the dominant focus in academic literature has been on how new information and communication technologies (ICT) and social media platforms have lowered barriers to information exchange and facilitated wider mobilization and participant-led advocacy.

However, as we show in our book, the impact of technology on climate activism extends far beyond mobilization and member-driven campaigning to dynamics of organizational formation and fundraising, data collection and research, lobbying, monitoring and enforcement. Empirically, the digital advocacy research agenda has been dominated by case studies from North America and Western Europe.

Yet, as we explore, digital advocacy is spreading fast among environmental groups in the Global South. These groups often use different technologies, and use technology differently, than groups in the Global North, frequently leapfrogging their northern counterparts in terms of innovative technology use.

More of the Same, Just Faster? Or Transformative Impact?

It is well understood that digital technology can enable activist organizations to reach public audiences and decisionmakers faster, and at lower cost. Since the 1990s, NGOs have used modern ICT to broadcast their messages faster and wider. Using ICT and social media to recruit new members or to spread ones’ message is generally cheaper and faster than door-to-door appeals or traditional forms of broadcasting like mail, radio or television. Yet, it does not fundamentally transform what activist organizations do or strive for.

New technologies are challenging the monopoly of the state over critical information and knowledge.

However, digital technology can also have more transformative effects, enabling activists to pursue entirely new strategies to advance their goals—or even changing the goals they pursue. Digital technologies can fundamentally refashion the collective action process, for example, by allowing individuals to eschew traditional brick-and-mortar organizations and use digital platforms to self-organize and ‘crowdfund’ activities.

Social media platforms also allow activists to test new campaign issues and strategic framings through ‘analytic activism‘ and to converse directly with members or potential supporters, tailoring their messages to the personal concerns of specific audiences. Many advocacy organizations we spoke to are currently experimenting with using AI to generate user-specific content and to enhance the effectiveness of their communication, for example by using AI to learn which forms of messaging are most likely to spark sustained engagement from different recipients.

Another transformative use of digital technology is to facilitate new social movements. Some national and local Greenpeace chapters have empowered their members to initiate their own campaigns, without reliance on Greenpeace staff. Fridays for Future has likewise distributed power to its members to set up their own local chapters, and to plan large street demonstrations at times and locations of their own choosing.

Transforming Activism: Digital Tools and New Strategies

In September 2019, Friday for Future coordinated marches in 183 countries through a simple on-line events map. Anyone, anywhere in the world, could join the global movement by launching their own action. This form of distributed, participant-led campaigning which hands initiative to individuals and small-scale collectives is important in empowering local stakeholders and marginalized groups, and in ensuring that climate activism speaks directly to local concerns.

Beyond social-media, digital technologies like satellite, drones, geographic information systems (GIS) and ‘open data’ has potential to transform climate activism by facilitating new forms of evidence collection. Once the preserve of national militaries, research labs and large corporations, satellite-based remote sensing and GIS mapping are now used by NGOs to collect and analyze data on climate change indicators such as deforestation, changes in land use, GHG emissions, average rainfall, floodings, glacier melting, and more.

Both authoritarian and democratic regimes increasingly use technology to track, surveil, and repress climate activists.

Importantly, satellites, drones and other unmanned aerial vehicles can be used to monitor environmental factors in remote and inaccessible areas, like forests and oceans, where the causes and effects of climate change can be otherwise difficult to document—especially for non-state actors. New technologies are thereby challenging the monopoly of the state over critical information and knowledge.

Besides boosting monitoring, datafication and big data analytics afford unprecedented access to data with which activists can hold states and corporations directly to account for their (in)actions. Many NGOs today use advanced data analytics to process complex data such as satellite imagery and other geo-spatial information which they can use to track GHG emissions in real time and link these to individual firms.

While investigative journalism and independent investigations leading to lawsuits against polluters are nothing new, digital tools supercharge such strategies by lowering the cost of evidence gathering, and by enabling activists to produce a level of proof that would have been difficult in the pre-digital age. In our book, we illustrate how GlobalWitness used GIS and ‘open government data’ to establish a direct link between cattle farms in Brazil and rapid deforestation in the Amazonian rainforest. The result was a successful court case against one of the largest multinational beef traders in Brazil.

The Dark Side of Digitalization

Despite its promises, digital technology is not always empowering for climate activists. Following the euphoria of the 1990s when new ICTs were seen to seamlessly link activists across borders, allowing them to champion human and environmental rights and challenge corrupt regimes, today the downsides of digital advocacy are coming into clearer view.

The same technologies which connect activists to each other and to global audiences also pose new challenges and risks, including the spread of disinformation, widening digital divides, and digital repression. Brett Solomon, the founder and former executive director of Access Now, a global non-profit digital rights organization, puts it bleakly: “The internet has stopped being our friend and is increasingly becoming our enemy. The balance has shifted. Tech often weakens activists’ ability to achieve their goals.”

None of the trends and dynamics we identify in our book are driven by technological innovation alone.

One potential downside of technology-assisted advocacy is that reliance on digital platforms to mobilize public support risks leading to a culture of ‘slacktivism’ and ‘clicktivism’ whereby people engage with political causes in a fleeting and superficial manner that stands little chance of producing meaningful change. A related risk is that climate organizations chase “vanity metrics”; looking for viral online campaigns, without due attention to developing actions that actually challenge, or change, policy.

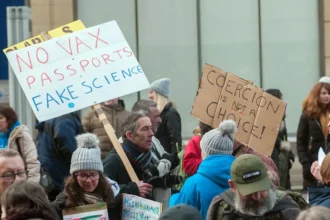

Digital activism may also carry greater risk of repression. When campaigning online, activists leave digital footprints, making it easier for governments and businesses to monitor their activities. Both authoritarian and democratic regimes increasingly use technology to track, surveil, and repress climate activists. Across the world, we find examples of environmental activists being targeted—even murdered—by state authorities that use facial recognition cameras and machine learning to suppress dissent.

Global Witness documented that 196 environmental defenders were murdered in 2023 after seeking to protect their lands and the environment from harm. These are just the cases that gain publicity; the actual number is likely to be significantly higher. Other recent studies found similar evidence of growing targeting of activists via digital platforms where they are identified, subjected to trolling, or doxed. Among those most vulnerable to online repression are indigenous climate activists seeking to protect their lands against logging and mining, and small island state activists campaigning for reduced emissions.

The Risks of Digital Activism: Surveillance, Disinformation, and Exclusion

Another obvious risk linked to digital climate activism is that political opponents may use the very technologies that are harnessed by pro-climate groups to campaign against climate action. Recent years have seen a rapid rise of online disinformation seeking to undermine climate science and advocacy. For example, automated bots and AI-powered algorithm generators have been found to shape climate discussion on online platforms like Twitter/X.

A 2020 report by Influence Map found that Facebook earned an annual revenue of $68 million from disinformation ads posted by known climate denier groups, while a 2023 report by Climate Action Against Disinformation showed that major fossil fuel companies were behind much online misinformation.

Our aim is to explore how different climate organizations are helped, hindered or harmed by technological developments.

Digitalization can also lead to new patterns of political exclusion, as uneven access to digital infrastructures and digital skills creates new social divides within and across countries. Recent research has found that global internet use is lower for women than for men, especially in low-income countries. More broadly, rates of internet access and ‘digital literacy’ tend to be higher in richer countries, in urban settings, and among socio-economically well-off groups.

According to World Bank and International Telegraph Union data, 90 percent of the population in high-income countries are online, compared with just 44 percent in developing countries. Broadband in wealthier countries is five to ten times faster than in low-income countries. Likewise, the skills necessary to navigate open-access data or build advanced algorithms tend to be concentrated among cosmopolitan, wired urban elites. Effectively, this means the populations most at risk from the impacts of climate change often have the least access to information about it.

Tech’s Dirty Secret

Digital advocacy is no panacea when it comes to fighting climate change. While many digital technologies may aid climate action, tech companies contribute to damaging the global environment through high energy use and reliance on scarce minerals. Colour displays, speakers, camera lenses, rechargeable batteries, hard drives, fibre optics, and other key elements in the digital revolution all rely on rare earth minerals.

Many of the trends we point to apply to social activism more broadly.

Lithium mines dotted across the world testify to the rampant ‘extractivism’ feeding the digital economy. Once used, these elements become sources of toxic waste.

With over six billion new ICT goods sold annually, e-waste has become the largest waste stream in many countries, with developing countries being the main recipients. Some forecasts suggest that, by 2030, nearly a quarter of all global GHG emissions will stem from communication technology production and use.

The Double-Edged Sword of Digital Technology in Climate Advocacy

Against this sombre backdrop, our book is not a celebration of technology. Our aim is to explore how different climate organizations are helped, hindered or harmed by technological developments. Drawing on interviews with dozens of activists, and building on existing scholarship in political science, sociology, law, and environmental studies, we examine how technology influences the formation, scope, and organizational structures of climate organizations around the world.

As our analysis shows, the way climate activists embrace technology differs significantly by country and region, and for different types of climate organizations; with smaller, and newly formed activist organizations often being more tech-savvy than older, well-established peers.

Crucially, we do not argue that climate activists are distinctive in their use of digital technologies. Many activist organizations and social movements use digital technology to organize and campaign – from the human rights movement to anti-corruption organizations. Many of the trends we point to therefore apply to social activism more broadly.

Equally, none of the trends and dynamics we identify in our book are driven by technological innovation alone. Instead, they arise from the way(s) in which new technologies interact with existing social, political, and economic structures to produce (or stifle) societal change. Our goal in writing this book has been to call attention to emerging trends in technology use among social and political activists, and to identifying critical questions for scholars and practitioners.

The questions we raise all call for further research from sociologists, legal scholars, political scientists and media experts, as well as input from activists to better understand the varied implications of technology-use. By highlighting the potential of digital technologies to transform climate advocacy, and by identifying both benefits, risks and challenges from technology use, we hope to start a wider conversation.