- Summary

- Introduction

- Why Was the EU’s Asylum System Developed and Reformed?

- The Main Deficits of the European Asylum System

- A New Start: The New Pact on Migration and Asylum

- Key Elements of the Agreed Reform

- A Political Success, but Many Critical Voices

- Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

- More Centralization – Improved Compliance?

- Human Rights and Legal Concerns

- More Asylum Externalization Likely

- Concluding Remarks

Summary

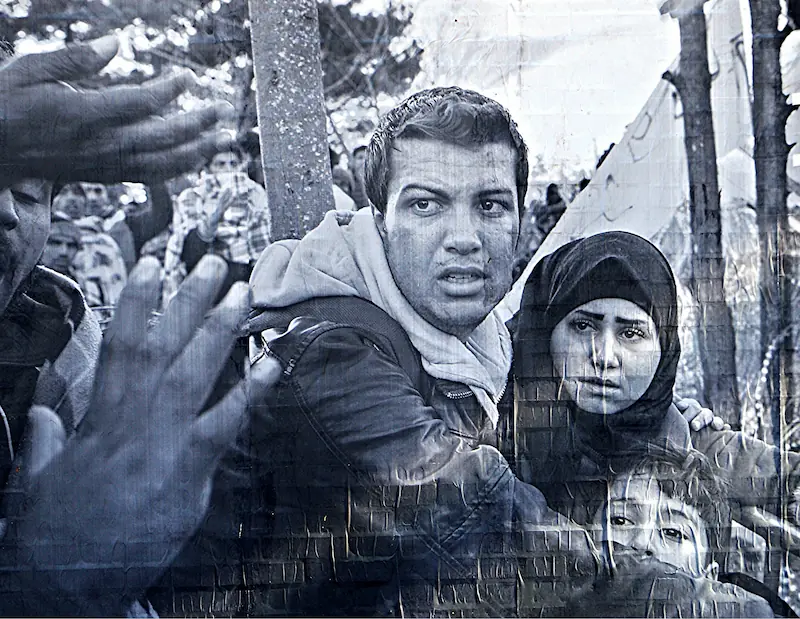

After lengthy negotiations and deep disagreements among the 27 member states of the European Union, the EU’s decision-making bodies last year finally reached an agreement on a major reform of the bloc’s ‘Common European Asylum System’. This reform package, based on the European Commission’s ‘New Pact on Migration and Asylum’ from 2020 and some earlier proposals, introduces numerous changes and new elements to how EU countries deal with asylum seekers.

The reformed system, which is planned to become operational in summer 2026, shifts much of asylum governance from the national to the EU level and tries to achieve more harmonized asylum practices in the member states. There are also huge risks, however, such as a weakening of asylum rights and the complexity of the new system making it difficult to function in practice. As many governments in Europe are now discussing even more drastic deterrence measures than those foreseen under the latest reform, the hard-fought compromise also seems fragile, and the future of asylum in Europe uncertain.

Introduction

In spring 2024, the EU’s member states and the European Parliament adopted a long-negotiated compromise on a comprehensive reform of the Common European Asylum System (CEAS). This reform is based on the ‘New Pact on Migration and Asylum’, proposed by the European Commission in 2020 and several earlier legislative proposals.

There are many risks and uncertainties regarding the new system’s stability, feasibility, and compliance with international asylum law principles.

The compromise consists of several revised and some entirely new EU laws, introducing significant changes in areas, such as screening of asylum seekers at the EU’s external borders; border procedures for asylum and return; responsibility-sharing among the EU member states; and emergency measures for migration crisis situations.

Starting with some historical background, this article aims to present an overview of the most important changes to the CEAS that have been decided, identify problematic aspects, and assess the likely consequences of the reform in terms of human rights compliance, functionality, effectiveness and the future direction of policy and legislation on asylum in Europe.

Why Was the EU’s Asylum System Developed and Reformed?

Three main factors can explain why the EU started, more than 20 years ago, to develop a common asylum system.

- The creation of a common market in the EU without internal border controls and passport checks between its member states was seen as necessitating common rules for who can cross the EU’s external borders.

- Political decision-makers in member states often faced obstacles when trying to reform national asylum and migration rules, leading them to shift decision-making to the EU level.

- Migration movements to the EU showed that national policies in one member state can affect migration flows to others.

The original CEAS was adopted between 2000-2005. It essentially comprised six laws (four EU directives and two EU regulations), which were revised between 2011-2013 to increase harmonization. However, the system faced pressure and partly collapsed during the 2014-2016 ‘refugee crisis’, which prompted calls for further reform.

The Main Deficits of the European Asylum System

Researchers and practitioners had also identified several fundamental problems and shortcomings of the CEAS, which also called for changes.

- The most systemic and critical issue is the absence of safe and legal routes for most asylum seekers to reach the EU. Despite the EU’s obligation to uphold the right to asylum, measures such as visa requirements, carrier sanctions, and border barriers force many asylum seekers to rely on dangerous and irregular routes as well as facilitation by human smugglers.

- The EU’s so-called Dublin Regulation, intended to determine, for each asylum seeker, one responsible member state, never fully functioned as anticipated. Significant variations in asylum decision-making practices, reception conditions, and asylum procedures across the member states (among other factors) have led to unwanted ‘secondary movements’ of asylum seekers from one member state to another. Member states have often not been able to transfer an applicant to the responsible member state. Instead of guaranteeing asylum seekers quick access to a procedure in a member state, the Dublin system has often been a waiting room for them. It has also contributed to a highly unequal distribution of asylum seekers across European states.

- There are wide differences in the approval rates for asylum seekers across the various EU member states, even for people from the same country of origin. For example, the approval rates for asylum seekers from Afghanistan have varied by up to 95 percentage points between member states, highlighting massive disparities in the assessment of protection needs (see here or here).

- Reception conditions for asylum seekers have also varied hugely, and in some member states, accommodation and services have been so bad that courts in other member states have halted Dublin transfers to these states, citing systematic deficiencies.

- Efforts to reform the asylum system have been hampered by political resistance in some member states to acknowledging the reception of asylum seekers as a common task. Mandatory redistribution of asylum seekers among the member states, something that many researchers, but also some political actors, have considered necessary for a more balanced European system, in which all member states take equal responsibility, has met fierce opposition.

A New Start: The New Pact on Migration and Asylum

After the 2019 European Parliament elections and the appointment of a new EU Commission, a new attempt was made to reform the CEAS. Earlier proposals (from 2016) had failed because some member states resisted enhanced burden-sharing.

Not all member states are convinced that the pact is the right approach.

The ‘New Pact on Migration and Asylum’, presented by the Commission in September 2020, consisted of several proposals for revised (or totally new) regulations and recommendations.

After difficult negotiations, a compromise was reached at the end of 2023 and got formally adopted in April (European Parliament) and May 2024 (Council). They are to be implemented and become operational by summer 2026.

Key Elements of the Agreed Reform

The key components of the final package can be summarised as follows:

- A new screening procedure aims to ensure that third-country nationals who have crossed an external border in an irregular manner are identified, registered, and quickly referred to appropriate follow-up procedures, such as asylum or return procedures. The screening must be completed within seven days at the border and three days if a migrant without valid documents is detected within the territory.

- A new Asylum Procedures Regulation aims to streamline, simplify, and harmonize asylum procedures across member states. It introduces different types of asylum procedures, including a faster border procedure for those with low chances of receiving protection and a longer normal procedure for people with higher chances of getting asylum. People in border procedures (and in screening) are to be considered as not being on EU territory, a so-called ‘fiction of non-entry’.

- A separate Regulation on Border Return Procedures applies to individuals whose asylum applications are rejected within the border procedure. They must remain at or near the external border or in transit zones for up to 12 weeks while their return or removal is prepared.

- A new Migration Management Regulation replaces the Dublin Regulation and introduces a new solidarity mechanism as well as a comprehensive framework for managing migration and asylum in the EU. While the responsibility-allocation criteria of Dublin, whereby many applicants are under the responsibility of the EU country they first arrive in, are essentially maintained, the regulation devises a planning cycle to ensure solidarity and fair responsibility-sharing. Member states that receive many more asylum applicants than others are entitled to get help – either by sending applicants to other Member States (‘relocation’) or in other ways. No state is however forced to take in relocated applicants; they can also contribute financially or through other means of support.

- A Crisis and Force Majeure Regulation provides special rules for handling mass arrivals of asylum seekers, force majeure situations (e.g., a pandemic), and the instrumentalization of migrants by hostile foreign powers. For example, it allows for certain exceptions to normal asylum rules, such as extended border procedures.

- The Eurodac system, in essence a database of asylum seekers and irregular border crossers, is expanded to include more biometric data and a broader range of individuals, including children. Data will be stored for longer periods, and the system is to be linked with other EU databases.

- A ‘Qualification’ regulation sets uniform standards for who qualifies for protection and the rights of those granted protection. It aims to harmonize asylum decision-making across member states and the rights and entitlements of refugees and people in need of subsidiary protection.

- The revised Reception Conditions Directive aims to further harmonize reception conditions for asylum seekers, which includes (basic) social welfare, housing, and the right to work. It also widens the use of detention.

- The EU now also has a common Resettlement Framework, which establishes common basic rules for the resettlement of refugees and humanitarian admissions. It does not force member states to actually take in resettled refugees, however.

- As agreed earlier, the former European Asylum Support Office was renamed ‘European Union Agency for Asylum’ (EUAA) and received a stronger mandate.

A few months after the final agreement on the new CEAS, the European Commission presented a comprehensive implementation plan to support member states’ complicated transition to the new system until 2026. The member states must prepare national implementation plans and make necessary legal, administrative, and operational changes within a two-year transition period.

A Political Success, but Many Critical Voices

The new migration and asylum pact undoubtedly represents a political success for the European Commission and other stakeholders who had advocated for a reform of this kind. Very different national interests were reconciled, notably those of countries of first arrival (such as Italy or Greece) and those further West and North.

However, not all member states are convinced that the pact is the right approach. The package passed the Council with a qualified majority, but Poland and Hungary voted against it and some others voted against parts of it. The stability and long-term viability of the pact are therefore uncertain. There were also disagreements among the different political groups in the European Parliament.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

Two days after the Council’s final vote in May 2024, interior ministers from 15 member states called for new measures to prevent irregular migration to Europe, suggesting changes to the just adopted Asylum Procedures Regulation, to make it possible to transfer asylum seekers to ‘safe’ third countries outside the bloc (‘externalization’). Another group of member states declared that they wanted to be able to suspend the right to seek asylum in cases where foreign powers instrumentalise asylum seekers to put pressure on the EU (as Russia and Belarus have tried to do). This indicates that the pact in its current form might be short-lived, or at least that the CEAS could be changed again soon.

The pact’s complexity also poses challenges. The new system includes multiple procedures with different timelines for various groups of asylum seekers, as well as exceptions and special rules for crisis situations. The solidarity mechanism and the new governance system, to be administered from Brussels, is highly intricate as well. This ‘byzantine’ complexity could make the system difficult to apply consistently across the EU member states, and there could be fights over member states’ solidarity contributions.

More Centralization – Improved Compliance?

The centralization of asylum management under the new rules aims to improve member states’ compliance with EU rules, and the introduction of a ‘planning cycle’ for migration management, including mandatory national asylum strategies, and an overarching EU strategy, a solidarity coordinator and new bodies for management and decision-making, is intended to enhance coordination and oversight. But whether this will work depends on the willingness of member states to comply with the new rules and indeed assist each other in a meaningful way.

The political debate in the EU has been dominated by calls to reduce ‘migration pressure’ and stop irregular border crossing.

Past experiences have shown that some member states have cared little about correct implementation of EU asylum law – there have been illegal pushbacks at various external borders, violence against asylum seekers, substandard reception conditions, among many other problems.

Over recent years, the European Commission has often tolerated this or looked the other way – likely because they did not want to upset member states during sensitive negotiations over the CEAS reform. Ensuring compliance with the new system will require robust monitoring and enforcement mechanisms – but also a political will. This has all been missing for years.

Human Rights and Legal Concerns

The reform has also raised concerns about its impact on human rights and the rule of law. Critics argue (here or here), for example, that the fast-track border procedures risk undermining the careful processing of asylum claims, which can clash with the principle of non-refoulement, and leading to a more widespread use of detention-like accommodation of applicants.

Access to effective legal remedies and possibilities to appeal negative asylum decisions could be limited. In situations where the number of asylum seekers is high, vulnerable people could suffer from protracted uncertainty about their right to stay and substandard accommodation.

There will likely also be a wider use of ‘safe country’ concepts, which means that more asylum claims are likely to be regarded as inadmissible. Asylum seekers who do not comply with the obligation to stay in the country that they are assigned to under the new responsibility-allocation system, risk ending up without any support.

Further to this, the fact that an average approval rate of 20% will be used as a threshold to determine whether a person from a certain country of origin will be processed in a border procedure, or in a normal asylum procedure, appears arbitrary. It could have been set higher or lower, and the EU approval rate is a fiction anyway because approval rates for asylum seekers from the same country often vary massively between different member states.

What will happen in crisis situations is also unclear. Asylum applicants could be faced with lengthy detention in border procedures and get removal orders without adequate assessment or safeguards.

More Asylum Externalization Likely

Already several months before the agreement between the European Parliament and the Council on the Pact, the EU intensified its efforts to seek migration agreements with third countries, mainly in North Africa, in an attempt to prevent irregular migration and smuggling of human beings across the Mediterranean. The driving force behind this was an increasing number of irregular arrivals and asylum applications in 2023, but possibly also a growing realization that the CEAS reform alone would not lead to fewer asylum seekers in the EU – at least not in the short term.

The political debate in the EU, however, has been dominated by calls to reduce ‘migration pressure’ and stop irregular border crossing, and this debate has escalated further after the adoption of the Pact. This indicates that even more activities in the external dimension of EU migration policy are to be expected, notably ideas to outsource or externalise asylum responsibilities of the EU to non-EU countries in the framework of what is often called ‘third-country solutions’. The European Commission’s President Ursula von der Leyen’s Political Guidelines for the 2024–2029 period announce the development of ‘strategic relations’ on migration with countries outside the EU, in particular transit countries, and ‘new ways of combating illegal migration’.

This all suggests that the Pact is not an end point in the development of the CEAS, but that is encourages even more measures to prevent irregular migration and limit the number of asylum seekers.

Concluding Remarks

The Migration and Asylum Pact certainly marks a historic step in the development of the EU’s common asylum and migration policy, promising increased harmonization, better cohesion, enhanced planning, and stronger solidarity among the EU member states. However, as this analysis has shown, there are many risks and uncertainties regarding the new system’s stability, feasibility, and compliance with international asylum law principles.

Until the new system starts applying (in summer 2026), it exists only on paper, and its real-world functionality remains to be tested. The complexity of the system will place high demands on the EU Commission and member states, and focusing on this task may be challenging when political decision-makers are already discussing changing the Pact again and various member states unilaterally take migration control and border policy measures that circumvent what both the current and the coming (but not yet implemented) EU asylum law allows.

The question is also what will happen to the fundamental flaws of the CEAS and the EU’s migration policy: the uneven distribution of asylum seekers in Europe (and the lack of solidarity among its member states); the strong variations in member states’ views on asylum seekers’ protection needs; and the lack of safe and legal pathways to seek protection in the EU, which has pushed people to undertake hazardous journeys.

The analysis shows that the Pact, if implemented correctly and functioning, could lead to some progress in terms of a somewhat fairer distribution of responsibility and somewhat more uniform decision-making in asylum cases. But there is nothing in the pact that suggests that migration flows into the EU will be redirected from irregular routes to safe and legal channels. Therefore, a reasonable conclusion is that the pact brings many regulatory and practice changes as well as a focus on heightened control and efficiency – while one of the most central fundamental problems remains unaddressed.

Given that the number of people who migrate to find protection remains high and that the EU should contribute to sustainable and fair global solutions, it is unlikely that the new legislation is an adequate development.

At the same time, it may be that the Pact, should the member states implement it in good faith, is a better way forward than a situation where they – in the absence of workable solutions at the EU level – unilaterally take increasingly drastic measures to keep asylum seekers away, thereby undermining the international protection system. This means that, as difficult and problematic as the Pact appears, it might still be better than many of the ‘solutions’ that EU policymakers have been discussing since its adoption.