Totalitarianism, at its core, refers to a political system where the state recognizes no limits to its authority and seeks to regulate every aspect of public and private life. It’s a system characterized by absolute centralized control, a single party led by a dominant leader, and the suppression of opposition. This extreme form of governance often employs propaganda, censorship, and state-controlled media to maintain its grip on power, ensuring that dissenting voices are silenced.

Cuba’s journey towards totalitarianism is deeply rooted in its tumultuous history. Following the Spanish-American War in 1898, Cuba emerged from Spanish colonial rule only to find itself under the influence of the United States. However, it was the Cuban Revolution of 1959 that marked a significant turning point. Led by Fidel Castro and his band of revolutionaries, this movement aimed to overthrow the authoritarian regime of Fulgencio Batista. Successful in their endeavor, Castro’s ascent to power signaled the beginning of a new era for Cuba.

Opposition parties were disbanded, and dissenting voices faced severe repercussions. Political opponents were frequently imprisoned, subjected to forced labor, or even executed.

Under Castro’s leadership, Cuba underwent dramatic transformations. Land and industries were nationalized, and ties with the U.S. deteriorated. As Castro solidified his rule, political opponents were swiftly dealt with, either through imprisonment or forced exile. The state took control of media outlets, ensuring a singular narrative dominated the Cuban airwaves. Over time, the Cuban government’s grip tightened, and the island nation evolved into a state where dissent was not tolerated, and freedoms, especially those of speech and assembly, were curtailed.

This evolution towards a totalitarian regime in Cuba was not just a result of internal dynamics. External factors, especially its alliance with the Soviet Union during the Cold War, played a crucial role. As the years progressed, the Cuban model of governance became deeply entrenched, with the state exerting control over every facet of its citizens’ lives, epitomizing the very essence of totalitarianism.

Brief History of the Totalitarian Cuban Regime

The Cuban Revolution, which culminated in 1959, marked a pivotal moment in the nation’s history. Fueled by widespread discontent with the authoritarian rule of Fulgencio Batista, a young revolutionary named Fidel Castro, alongside figures like Che Guevara, mobilized a guerrilla movement. Their aim was not just to overthrow Batista, but to reshape Cuban society. After a series of battles and strategic maneuvers, Castro’s forces emerged victorious, and he quickly ascended to the helm of Cuban leadership.

One of the hallmarks of the totalitarian Cuban regime’s grip on power is its intricate system of state control mechanisms.

With Castro in power, the process of consolidating his rule began in earnest. Nationalization of industries and land reforms were swiftly implemented. However, these economic changes were accompanied by a more sinister political agenda. Opposition parties were disbanded, and dissenting voices faced severe repercussions. Political opponents were frequently imprisoned, subjected to forced labor, or even executed. The media landscape was altered, with the state taking control of newspapers, radio, and television stations. This ensured that only the government’s narrative, free from criticism or opposition, reached the Cuban populace.

But Castro’s Cuba did not operate in isolation. The geopolitical landscape of the time, dominated by the Cold War, played a significant role in shaping Cuba’s trajectory. As relations with the United States soured, marked by events like the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis, Cuba found an ally in the Soviet Union. This alliance was not merely ideological; it had tangible impacts. The Soviet Union became Cuba’s primary trade partner and benefactor, providing economic aid, military support, and serving as a counterbalance to U.S. influence in the region.

With the backing of the Soviet Union, the totalitarian Cuban regime further solidified its grip. This relationship provided Castro’s government with the resources and support needed to suppress internal dissent and strengthen its authoritarian rule. Over the years, the intertwining of Cuban and Soviet policies and ideologies solidified Cuba’s position as a key player in the global Cold War dynamics and as a staunch bastion of totalitarianism in the Western Hemisphere. Recently, the authoritarian Russian government and Cuba have strengthened ties, with the Cuban totalitarian regime even supporting the invasion of Ukraine.

State Control Mechanisms in Cuba

One of the hallmarks of the totalitarian Cuban regime’s grip on power is its intricate system of state control mechanisms. These tools, both overt and covert, have been instrumental in maintaining the government’s dominance and suppressing dissent.

Central to this control is the state’s stranglehold on media and communication. In Cuba, the media is not an independent watchdog but an arm of the state, ensuring that the narrative remains consistent with government ideology. Newspapers, television, and radio stations are all state-owned and operated, effectively eliminating any platform for dissenting voices.

Political repression is rampant, with dissidents frequently arrested, often without formal charges or trials.

This centralized control extends to the digital realm as well, with restricted internet access and heavy online surveillance. The result is a curated information environment, where the populace is exposed only to state-sanctioned content, free from external influences or internal criticisms.

Complementing this media control is an extensive surveillance apparatus. At the heart of this system are the Comités de Defensa de la Revolución (CDR), or Committees for the Defense of the Revolution. Established shortly after the revolution, the CDRs are neighborhood-based organizations with a presence in every corner of Cuba. While they undertake various community roles, their primary function is to monitor and report on the activities of Cuban citizens. This grassroots surveillance ensures that dissent, or even potential dissent, is quickly identified and addressed.

But the state’s control is not just about monitoring; it’s about active repression. Those identified as opposing the government, whether through their words or actions, face severe consequences. Political repression is rampant, with dissidents frequently arrested, often without formal charges or trials. The conditions in Cuban prisons are notoriously harsh, with reports of torture, forced labor, and denial of medical care. This climate of fear, perpetuated by the threat of imprisonment or worse, serves as a powerful deterrent, ensuring that many Cubans think twice before voicing their opposition or engaging in activities deemed counter to the state’s interests.

Economic Foundations of Totalitarian Control in Cuba

The economic landscape of Cuba, shaped by decades of policy decisions, serves as a foundational pillar for the state’s totalitarian control. By intertwining economic structures with political objectives, the totalitarian Cuban regime has crafted a system where economic dependence reinforces political loyalty.

The nationalization of industries and properties was one of the first major economic shifts post-revolution. Private enterprises, large estates, and foreign-owned assets were swiftly brought under state control. This move was not merely economic but also political, aiming to dismantle the economic power bases that could challenge the new regime. By centralizing economic assets, the state ensured that economic prosperity and livelihoods were directly tied to the government’s whims and policies.

Those who aligned with the state’s objectives and ideologies found themselves in favorable economic positions, while dissenters faced economic hardships or even joblessness.

This centralized economic structure created a scenario where most of the Cuban populace became economically dependent on the state. Jobs, wages, and opportunities were all controlled by the government, making economic mobility and independence a challenge. This economic dependence became a potent tool in the state’s arsenal, allowing it to reward loyalty and punish dissent. Those who aligned with the state’s objectives and ideologies found themselves in favorable economic positions, while dissenters faced economic hardships or even joblessness.

Furthermore, the state’s control over resource distribution, particularly through rationing systems, reinforced this dynamic. Basic necessities, from food to medicine, were often distributed based on a rationing system, ensuring that every Cuban household’s sustenance was linked to the state. This system not only allowed the government to manage scarce resources but also served as a constant reminder of the state’s role as provider and gatekeeper.

The totalitarian Cuban regime has adeptly used economic structures and policies as extensions of its political objectives. By intertwining the two, it has created a scenario where economic dependence and political loyalty are inextricably linked, further solidifying its totalitarian grip on the nation.

Education and Propaganda: Tools of the Cuban State

In the architecture of Cuba’s totalitarian control, the education system stands as a cornerstone. Through it, the state has not only disseminated knowledge but also shaped ideologies, ensuring that successive generations align with the government’s narrative. The totalitarian Cuban regime has adeptly used history and culture as tools of propaganda.

The totalitarian Cuban regime has adeptly used history and culture as tools of propaganda.

Central to this endeavor is the use of the education system for indoctrination. From primary schools to universities, curricula are designed to emphasize the virtues of the revolution and its leaders. Lessons often intertwine academic content with political ideology, ensuring that students not only learn mathematics, science, and literature but also absorb the state’s perspective on socialism, and Cuban identity. This educational approach ensures that from a young age, Cubans are embedded with a worldview that aligns with the state’s objectives.

Parallel to this educational indoctrination is the promotion of the cult of personality, particularly around figures like Fidel Castro and Che Guevara. These leaders are not just presented as political figures but are elevated to near-mythic statuses. Their images adorn classrooms, textbooks, and public spaces, and their speeches and writings become integral parts of the curriculum. By doing so, the state ensures that these figures are revered, their ideologies internalized, and their leadership seen as both essential and benevolent.

As has always been common in communist countries, the totalitarian Cuban regime has adeptly used history and culture as tools of propaganda. Historical events, especially those related to the revolution, are presented in a manner that emphasizes the heroism of the revolutionaries and the righteousness of their cause. Cultural expressions, whether in the form of music, art, or literature, are encouraged when they align with the state’s narrative and suppressed when they challenge or critique it.

In sum, through a combination of education and propaganda, the Cuban state has crafted a narrative that reinforces its legitimacy and control. By controlling the lenses through which Cubans view their history, leaders, and cultural identity, the state ensures a populace that is not only knowledgeable but also ideologically aligned.

Foreign Relations and Diplomacy: Cuba on the Global Stage

Cuba’s position in international relations is a complex tapestry woven from its revolutionary history, strategic alliances, and its enduring tussle with superpowers. This intricate dance of diplomacy has played a pivotal role in shaping Cuba’s domestic and foreign policies.

On the global stage, Cuba has often portrayed itself as a beacon of resistance against imperialism and a champion of the non-aligned movement. This stance, rooted in its revolutionary origins, has garnered both admiration and criticism. While some nations laud Cuba for its resilience and defiance against Western hegemony, others view it as an outlier, often due to its human rights record and political system.

The fulcrum of Cuba’s foreign relations has undeniably been its tumultuous relationship with the United States. From the very outset, post-revolutionary Cuba found itself at odds with its northern neighbor. The U.S. embargo stands as a testament to these strained ties. This embargo, coupled with incidents like the Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis, has ensured that U.S.-Cuba relations remain a topic of global interest. Over the years, while there have been moments of détente and attempts at diplomacy, the relationship remains characterized by deep-seated mistrust and ideological differences.

Yet, Cuba’s diplomatic endeavors are not limited to its interactions with the U.S. Its participation in international bodies, notably the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), showcases its desire to be an active player in global affairs. While Cuba’s membership in such organizations is often contentious, it provides the nation with a platform to voice its perspectives and challenge critiques. Moreover, it offers an opportunity for Cuba to shape its image, presenting itself as a nation committed to global cooperation and dialogue, even as it faces criticism for its domestic policies.

Exile as a Tool of Control: The Cuban Diaspora’s Complex Legacy

Exile has long been a potent tool in the arsenal of the Cuban state, serving both as a method of control and as a reflection of the island’s tumultuous political landscape. The history of Cuban exile is a tapestry of personal tragedies, political maneuverings, and a diaspora’s enduring connection to its homeland.

The narrative of Cuban exile began in earnest following the 1959 revolution. As the new regime solidified its grip on power, those who found themselves at odds with its ideologies or policies faced a stark choice: stay and risk persecution or flee in search of safer shores. This initial wave of exiles, comprising political dissidents, intellectuals, and members of the former elite, set the stage for a phenomenon that would continue for decades.

Forced exile emerged as a deliberate strategy of the Cuban government. By pushing outspoken critics and potential threats out of the country, the regime achieved a dual objective. Firstly, it rid itself of immediate challenges to its authority within national borders. Secondly, by branding these exiles as traitors or mercenaries, it sought to discredit their narratives and critiques on the international stage. This tactic of forced exile was not a passive act but a calculated move, often involving threats, intimidation, and the leveraging of familial ties to coerce individuals into leaving.

Yet, the story of Cuban exile is not just one of repression but also of resilience. The Cuban diaspora, spread across various countries but most notably in the United States, has played a crucial role in preserving Cuban culture, history, and political discourse. This diaspora, while physically removed from the island, remains deeply connected to it, both emotionally and politically. Their experiences, narratives, and advocacy have ensured that the realities of life in Cuba, and the challenges posed by the regime, remain in global consciousness.

Forced exile has taken on a new dimension in recent years as dissenting voices began to rise. It transitioned from being a weapon for exceptional circumstances to tragically becoming a normalized method to silence opposition. The experiences of individuals like Camila Cabrera Rodríguez, Carolina Barrero, and Daniela Rojo are testament to this approach. Confronted with threats, harassment, and the possibility of incarceration, these young women represent just a fraction of the many individuals the government has forced out of the country, in some instances threatening harm to their friends or family.

The regime’s reach is not limited to within Cuba’s borders. The refusal to allow individuals, such as Professor Omara Ruiz Urquiola, to re-enter after traveling abroad highlights the government’s far-reaching influence. This strategy is not just punitive but also sends a stark warning: the regime’s power extends beyond the nation’s boundaries.

Challenges to Totalitarianism: The Rise and Response to Opposition Movements

Throughout its history under a totalitarian regime, Cuba has witnessed waves of resistance and opposition. These movements, while varied in their nature and objectives, share a common goal: challenging the state’s absolute control and advocating for greater freedoms and rights.

Historically, Cuba has seen numerous protests and dissident movements. From intellectuals and artists advocating for freedom of expression to grassroots organizations pushing for political reforms, these movements have been diverse in their composition and objectives. Some, like the Varela Project, sought change through legal and constitutional means, while others adopted more direct methods of protest and civil disobedience.

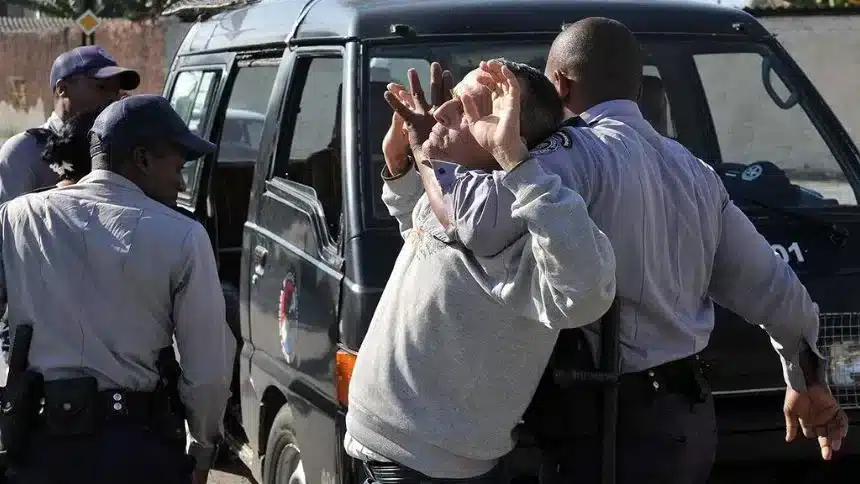

The Cuban government’s response to such dissent has been consistent: swift and often severe. Dissidents have faced a range of repercussions, from surveillance and harassment to detention and imprisonment. The state’s apparatus, including its security forces and judicial system, has been mobilized to suppress opposition, often under the guise of protecting national security or preserving the revolution’s gains. This pattern of repression has ensured that while dissenting voices emerge, they often face significant challenges in sustaining their movements and achieving their objectives.

However, the advent of technology and the rise of social media have introduced new dynamics to this age-old struggle. Digital platforms offer dissidents a space to share their narratives, organize movements, and connect with international audiences. The recent wave of protests in Cuba, fueled in part by social media campaigns and online mobilization, underscores the transformative potential of these tools. The state, recognizing this threat, has responded with internet shutdowns and digital surveillance, attempting to curtail the influence of online activism.

In essence, while the totalitarian Cuban regime has maintained its grip on power through a combination of political maneuvering and repression, it faces an evolving landscape of resistance. Modern technology, coupled with the enduring spirit of the Cuban people, presents new challenges to the state’s totalitarian control, signaling the possibility of change in the future.

11J: The Cuban Government’s Crumbling Facade of Popular Support

Despite the systematic repression exerted by the Cuban government over the past 60 years, they held a complete monopoly on information. Through relentless propaganda, the Cuban totalitarian regime managed to convince many that, even with its stern approach towards certain minority dissident groups funded by the United States, the government enjoyed widespread support from its citizens.

As a result, to some observers, Cuba was conveniently perceived as a democracy that, albeit illiberal, grounded its legitimacy in the principles of sovereignty and popular self-determination. However, the protests that erupted that day shattered any illusions for those who either believed or chose to buy into the government’s rhetoric. Across every province of the country, hundreds of thousands of Cubans took to the streets demanding a democratic transition, chanting “freedom,” “we are no longer afraid,” “we don’t want communism,” and “down with the dictatorship.”

These protests, an unprecedented event in over 60 years of dictatorship, were the crystallization of a set of factors, including the popular discontent about a government that is not seen anymore as a legitimate one, as is shown by the upward trend in the number of political protests in Cuba. It suffices to recall that in January 2021, there were 79 political and civil protests in Cuba, whereas in April of that same year, the number recorded by the Cuban conflict observatory was 156, which in July rose to 435, representing a 450% increase.

The Cuban Human Rights Observatory recorded, just one month before the social explosion, 713 repressive actions against the civilian population, including arbitrary detentions and other abuses (the total number in 2021 was 9,705, including 2,717 arbitrary detentions and 3,743 illegal house arrests).

It would then be incorrect to understand the demonstrations of July 11 exclusively as an expression of the country’s economic and health crisis. Although the situation in Cuba worsened considerably with this crisis, the videos recorded by the demonstrators show the Cuban people demanding freedom and rights.

The Iron Fist: Escalating State-Endorsed Repression

Instead of listening to the people’s demands, the non-elected President of Cuba publicly ordered the “revolutionaries” to repress peaceful demonstrators. Young Cubans of military service age, which is mandatory in Cuba, were forcibly recruited from their homes. They were given sticks to beat the protesters.

There are recorded images of the police beating indiscriminately. There are videos in which state forces burst into houses, abduct and, in at least one case, shoot a person in front of their family. After the demonstrations were repressed in the streets with gunfire, beatings, and trained dogs, state security agents and police began visiting the homes of identified protesters to arrest them.

The siege on the protesters’ homes, threats to their families, harassment and surveillance, internet cut-offs, high fines, acts of repudiation, job dismissals, forced exile among others, quickly became the new norm in Cuba. Decree-Law 35 came to reinforce controls over freedom of expression in social media in Cuba, contravening the provisions of articles 8, 40, 41, 47, 54, and 228 of the Constitution of the Republic of Cuba, as well as the international treaties ratified by the Cuban government.

Teenagers testified about being threatened with rape by state agents; students reported being tortured and sexually humiliated; demonstrators were prosecuted and imprisoned for promoting respect for fundamental rights; poets were harassed by police in their homes; children between 13 and 17 years were detained and journalists forced to stay at home for months. Many have been sentenced in summary trials without the right to a lawyer since the days following the protests.

A report by the NGO Prisoners Defenders asserts that, as a result of the protests of July 11, more than 5,000 people have been detained and more than 1,500 have been criminally prosecuted. Among these prisoners are minors under 13 years of age. The list of political prisoners includes 32 boys and 4 girls, of whom 2 girls and 7 boys have already been sentenced to high penalties of deprivation of liberty for sedition. Of the demonstrators, 167 had already been sentenced for this same cause, some with sentences ranging from six to 30 years.

Concerns Over Due Process and Judicial Integrity

According to Human Rigths Watch, many detainees in Cuba reported inhumane conditions including overcrowded and unsanitary cells, as well as limited access to basic necessities like food and clean water. They were subjected to repeated, often irrelevant interrogations that sometimes involved threats and physical abuse, including torture.

Legal proceedings against them frequently lacked due process; they faced “summary trials” with vaguely defined charges and were often without legal representation, or were subjected to “ordinary trials” that contravened international law.

These trials criminalized actions that are internationally recognized as legitimate exercises of freedom of expression and association, such as peaceful protesting or criticizing government figures. Convictions were often based on unreliable or uncorroborated evidence, such as sole testimonies from security officers or dubious “odor traces,” thereby raising serious concerns about the fairness and integrity of the Cuban judicial process.

The protests of July 11 and the testimonies of civilians who were victims of torture, mistreatment, and humiliation contributed to making visible the patterns of control and repression that characterize the totalitarian Cuban regime. A scientific study based on more than a hundred randomly selected cases submitted to the United Nations Committee against Torture shows 15 types of torture/mistreatment that political prisoners in Cuba are usually victims of.

The report mentions the intentional deprivation of medical care to those who need it (100% of the prisoners), as well as the deprivation of communication (84.09%), sleep (51.14%), and liquids and food (35.23%). It also points out solitary confinement (56.82%); highly uncomfortable, harmful, degrading, and prolonged postural patterns (43.18%); threats (78.41%); beatings (51.14%); the spread of excrement or urine in food or water (4.55%); confinement in cells infested with rats, insects, or with extreme cold or heat (40.91%), and more.

17M: Massive Protests Against Economic and Political Suffocation

On March 17th 2024, the flame of mass protests was reignited in Cuba, marking another significant chapter of popular dissent on the island.

This time, the epicenter of discontent was Santiago de Cuba, specifically in the Reparto Veguita de Galo neighborhood. In the afternoon, residents took to the streets, driven by the persistent lack of electricity supply and acute shortage of basic foodstuffs. Under the slogan “power and food,” a multitude of citizens gathered on Avenida de Carretera del Morro, voicing a call for change and chanting “Homeland and Life” in the presence of police officers and plainclothes agents, tangible symbols of state repression. While some areas of the nation experienced connectivity cuts, others saw the state telecommunications entity ETECSA, part of the GAESA military-business conglomerate, opt for a total interruption of internet access, replicating tactics observed in the 11J protests but with more effective execution, a result of prior experience.

In the city of Bayamo, discontent also spilled into the streets. Despite the intimidating presence of special units known as “black wasps,” and the strategic closure of various roads in anticipation of repression, citizens expressed their dissent vehemently. The tension escalated until the regime unleashed its repressive force against the protesters. Social networks were flooded with images and videos showing police officers using violence to subdue and arrest citizens attempting to evade detention.

As night fell, but with no signs of the protest spirit diminishing, Bayamo became the scene of a peaceful march. Lit only by the light of their cellphones, hundreds of protesters walked its streets to the sound of the National Anthem, in a display of unity and resistance, while cries for freedom echoed, as captured in recordings circulating on digital platforms.

The ripple effect of the protests was not limited to Santiago de Cuba or Bayamo. In Cárdenas, Matanzas, as night fell, the community joined the national protest movement, taking to the streets to the rhythm of pot-banging, adding their voice to the growing chorus of discontent that, once again, challenged the authority of the Cuban regime.

Envisioning Cuba’s Path Forward

As we reflect upon Cuba’s intricate tapestry of history, politics, and society, the question of its future trajectory looms large. The nation stands at a crossroads, with the weight of its past shaping the possibilities of its future.

The potential for change in Cuba is undeniable. Throughout its history, despite the challenges of a totalitarian regime, the spirit of resistance and the desire for freedom have persisted. This resilience, coupled with the evolving global landscape and the advent of technology, suggests that Cuba may be on the cusp of a new era. However, the path to meaningful change is neither linear nor guaranteed. It requires not just internal will but also external support and understanding.

The preservation of historical memory is paramount in this journey. For Cuba to move forward, it must reckon with its past. This process of introspection ensures that future generations are informed by the lessons of history, preventing the repetition of past mistakes and guiding the nation towards an inclusive and democratic future.

Equally crucial is the role of the international community. Cuba does not exist in isolation; its fate is intertwined with global dynamics. The international community, through diplomacy and advocacy, can play a pivotal role in supporting Cuba’s evolution. By engaging with Cuba constructively and recognizing the complexities of its history and politics, the global community can be a catalyst for positive change.

While the challenges facing Cuba are significant, so too are the opportunities. With a rich history, a vibrant culture, and a populace known for its resilience and creativity, Cuba’s potential is boundless. As the nation looks to the future, it does so with the hope of a brighter, freer, and more prosperous tomorrow.