The understanding of the African past has been revolutionised in the six decades since African nations’ wave of independence in the 1960s. UNESCO’s massive General History of Africa project and recent TV series like Zeinab Badawi’s BBC History of Africa series have ensured a big expansion of the public understanding of the African past. Meanwhile, accessible biographies of important figures such as Njinga – the 17th century queen of Matamba, in today’s Angola – have ensured that this understanding has been consolidated.

In fact, as all this work has also shown, African history as a discipline comes up against many of the issues facing historians of other world regions. This is particularly true for the early modern period. As with the Western past, there is a dearth of historical materials – both oral and written – historicising non-elite figures from the African past.

Historians who work on the distant African past are lucky to have an enormous range of sources produced by African historical subjects.

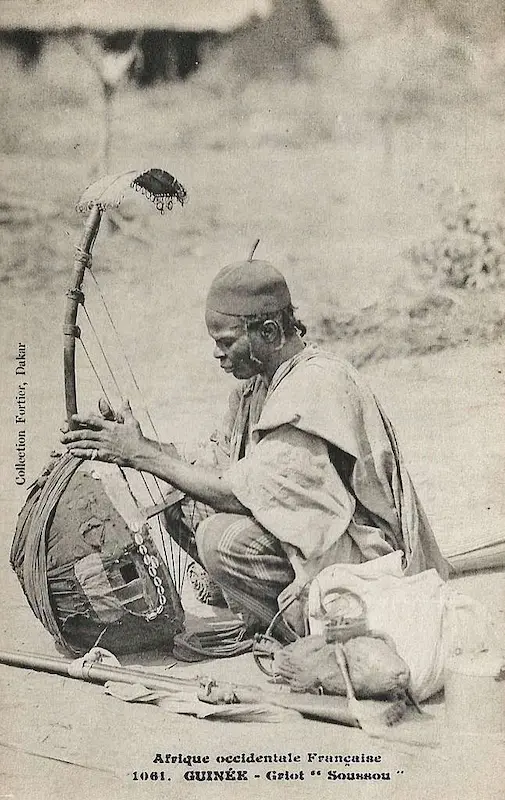

Indeed, court historians in West Africa were also, as in Europe, often lackeys of the ruling class in search of royal favours. This was at least partly true of the griots (praise singers) in Manding societies of Senegambia, just as it was true of Portuguese royal chroniclers of the 15th and 16th centuries such as Rui de Pina and João de Barros. The danger for historians is that this risks turning histories of early modern Africa into histories of elites, as if this is all that matters or in fact exists in the historical record.

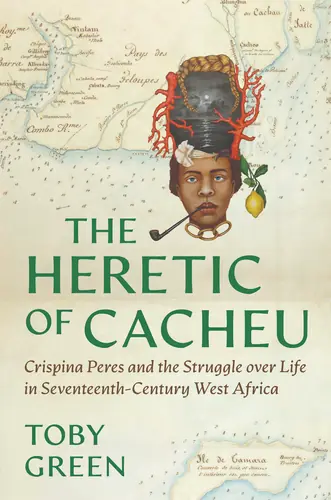

In my new book on daily life in the 17th century in the town of Cacheu in today’s Guinea-Bissau, I’ve tried to address this by taking a microhistorical approach to this past. How can zooming in to small details of the daily lives of African women and men challenge this approach, and offer a different perspective on the past to complement the important political histories that are also being written?

Microhistories and the Datafication of History

A generation ago, microhistories were all the rage in early modern history. Books such as Montaillou by Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie and The Cheese and the Worms by Carlo Ginzburg offered detailed approaches to the textures of life in late medieval Occitan and 16th-century Italy. Drawing on Inquisition sources, Ladurie and Ginzburg pioneered an approach that was said to revolutionise social history and offer a much more detailed awareness of the experience of past daily life than historians had produced before.

As the field of history became more global around the turn of the millennium, historians became aware of the potential of this approach for the global empires of Portugal and Spain in which the Inquisition also operated. In 2011, James Sweet published a book on the healer Domingos Álvares. Born in modern-day Benin, Álvares had been enslaved and shipped to Recife in northern Brazil: here he had been enslaved initially on a sugar plantation, until awareness of his healing powers grew, and he had ended up buying his own freedom and working as a healer in Rio de Janeiro, where people from all races and classes numbered among his clients.

Nevertheless, as Sweet’s book came out, a new trend was gathering in the field of African diasporic history. This was the increasing interest in datasets as a means for better mapping and understanding the routes of the diaspora in the Atlantic world. This interest itself grew from the increasing funds available to finance this research, and resulted in the publication of important databases freely accessible to the public such as slavevoyages and the Louisiana Slave Trade database.

Beyond the funding available from government and philanthropic foundations for this research, there were several drivers which went with this trend in African diaspora history. First was the fact that the traffic in enslaved Africans is one of the best documented of all processes for the early modern period: this was a ‘business’ on which huge fortunes hung, and thus its investors and agents were keen to track every aspect of their dealings in case it should be needed in any court of law in which this “historicizing” of the past of the enslaved should prove useful (something very well explored in a new book by Maria Montalvo, Enslaved Archives).

Second, and just as significant, was the rise of digital history as a field. The expansion of computation and the datafication of social trends and historical processes has been a key aspect of the field of history (and indeed of life) since the late 1990s. As computing absorbs many parts of daily life, this inevitably is reflected in the types of historical analysis and history produced.

However, a consequence of this is that the potential and importance of microhistorical approaches can be lost. When there can be such a profusion of detail, of data, why pick out just one aspect of it to home in on?

As AI grows year on year and the capacity for human subjects to produce thought independent of computation begins to feel eroded, The Heretic of Cacheu is my effort to answer this question.

Two Inquisition Trials from 17th-Century West Africa

The Heretic of Cacheu is a book building on the tradition established by Ladurie, Ginzburg, and Sweet, drawing on Inquisition trial records and other documents to reconsider aspects of daily life and social histories from the African past. However, where Ladurie and Ginzburg’s were resolutely local histories, I follow Sweet in bringing the global dimension of social life to the foreground.

That such a book can be written at all is something of a miracle. Only two Inquisition trials were produced in this part of West Africa during the entire 17th century. However, these trials were connected to one another, and took place within the same decade (1657-1668). Each trial is long, so there are over 1000 folios of trial records. Alongside these are another set of Inquisition records, account books seized from a slave trader in Lima, Peru, in the 1630s. All in all, there is more than enough material for a historian to work from.

The first trial was of Luis Rodrigues, a reprobate priest from the Cape Verde islands whose enemies conspired to denounce him. Rodrigues had been parish priest in Farim, a town three days’ journey upriver from Cacheu, and his life there produced all kinds of accusations: drunken parties, debauchery, shoot-outs in the streets, and affairs with married women whose husbands wanted to kill him. Rodrigues was tried by the Inquisition for soliciting women in the confessional – but he was acquitted, essentially because his accusers were Black women and lacked the racial and social status to have credibility in the Inquisition court of Lisbon.

When Rodrigues returned to Cape Verde, however, his property was in ruins. He determined to gain revenge on his enemies, and so got himself made inquisitorial visitor to Cacheu. There he set about fomenting trial papers against Crispina Peres: she was the most powerful trader there, and the wife of someone he had claimed as a sworn enemy in his own trial, the former Captain-General of Cacheu Jorge Gonçalves Frances.

The details of these trials begin to reveal the depth which these documents give when thinking about the role of empires in the African and global past. One stands out to me: when Crispina Peres was eventually deported for trial in Lisbon, her interpreter there was Manoel d’Almeida, the very same man who had also been responsible for bringing her in chains by ship from West Africa.

The way in which gendered inequalities, power, injustice, and cruelty intersect in this one anecdote unpeel the carapace from the emerging monolith of European empires in the early modern world. Almeida was indeed shortly promoted to be Captain-General of Cacheu – he died two years later, defenceless before the violent futility of his own ambition.

Microhistories and the Experience of the Past

Through following these threads of micro-detail in the trials, many vital aspects of the African past in its global context emerge – in a way which give them an urgency and salience which can be lost in a more data-driven approach.

We can consider some of the turns of phrase from the trials. At one point Crispina’s husband, Jorge, describes how in Guinea people “often turn a fly into an elephant” – indicating the culture of orality and exaggeration, the circulation of news, and how important a part this was of daily life. Elsewhere, Sebastião Rodriguez Barraza, a witness against Crispina who was an enslaved member of her household, said, “our Vicar did not beat a slave with a stick, which means that he has not spoken”. From this, we can gain a painful and grim sense of the workaday nature of beatings of the enslaved in a port like Cacheu.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

In fact, these documents give us a much richer insight through such details into the daily experience of the Atlantic traffic in the enslaved. We learn of people’s desperation to be free from their own mouths, and how this could lead them to take apparently rash actions to try and free themselves from their ‘legal owners’.

One almost throwaway line from the trial reveals oceans when it comes to this desperation. One witness, Maria Mendes, described how “the blood…was poured into the sea by a Black female slave of Crispina Peres who later would go to the Spanish Indies”. In other words, her status as a household slave was not enough to protect people from being clapped in chains, branded, canoed out to one of the waiting floating tomb-ships, and transported to the Americas.

It was a fate which could await any one of them, if the accounting books of credit and debt so demanded: and this gives an added sadness and poignancy in reading of the lives of those who tried to escape as best they could this Demon slavery, as Tiya Miles so eloquently puts it in her new book on Harriet Tubman Night Flyer.

These examples exemplify what microhistory has to offer in the study of this quite distant time in the African past. The emotions that people could feel at the prospect of enslavement and deportation to the Americas are revealed with a power that is beyond data. Here history is recovered in terms of the historical experience and not through the objectified and econometric cruelty of the historical process – something that much history written of the African diaspora also seeks to achieve.

Conclusion: Beyond the Objectification of the Past

Historians who work on the distant African past are lucky to have an enormous range of sources produced by African historical subjects. These range beyond texts produced in Arabic and Amharic, to letters written in Kikongo and Portuguese by Kings of Kongo, and huge numbers of material artefacts and objects which themselves contain whole worlds – as the historian Ana Lúcia Araujo has shown beautifully in her recent book The Gift.

One of the problems facing historians of this past with the rise of digital history and AI is the unspoken way in which historical subjects are recast as the historical objects – or ‘data points’ – which their enslavers intended to emerge from the historical record. The urgency of finding materials which can provide a different approach to this past therefore becomes more urgent than ever.

These Inquisition records may seem curious candidates for this effort. But in fact, an argument can be made that they were produced at least in part by African historical subjects. For many of those who served as scribes and witnesses were themselves born on the continent, and were usually of African heritage.

Through looking at the careful details recorded of such distant lives – of elite women like Crispina Peres, and also many who were not members of elites – historians can make a small effort to reset the balance in the era of digital history. For datafied history which does not recognise the centrality of the historical experience in its discourse ultimately reduces history to an object of study. In doing so, the concerns of those who struggled against the violent currents of history – historical subjects who produced the sources on which historians rely – are increasingly banished from the memory of the past.