Genesis of the Book: A Historical Perspective on Censorship

The inception of this book, an essay on censorship from yesterday to today, from Roman antiquity through the first decades of the 21st century, stems from the desire to provide readers with sufficient perspective to better analyze the current resurgence of what was known in the 19th century as “Madame Anastasie.”

- Genesis of the Book: A Historical Perspective on Censorship

- A Project Transformed by Circumstances

- The Many Faces of Censorship

- Censorship Through the Ages

- Morality and Social Movements: New Fronts of Censorship

- The Impact of Technology on Censorship: Current Challenges

- Towards a New Era of Censorship: Reflections and Future Challenges

Having worked on these issues for over thirty years and organized numerous symposiums on the topic, both in France and Quebec, I was approached in 2017 by the International Alliance of Independent Publishers to collaborate with a sociologist on a book about censorship worldwide.

Various forms of censorship extend beyond religion into political, economic, and increasingly moral and communal realms.

Among these symposiums, there was “Censorship in France in the Democratic Era (1848-…),” led by Pascal Ory and published in Brussels by Complexe in 1997, which compiled the proceedings of a symposium held in Bourges in 1994. Then there was “The Censorship of Print Media: Belgium, France, Quebec, French-speaking Switzerland, 19th and 20th Centuries,” led by Pascal Durand, Pierre Hébert, Jean-Yves Mollier, and François Vallotton, published in Montreal by Éditions Nota Bene in 2006, presenting the results of the Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines symposium held in 2002, and finally “Censorships in the World: 19th-21st Century,” led by Laurent Martin, which compiles the proceedings of the Paris symposium organized in 2014.

Prior to this volume, the Alliance was to interview dozens of publishers, English-speaking, French-speaking, Spanish-speaking, Portuguese-speaking, Arabic-speaking, and Persian-speaking, distributed across all continents, to gather their testimonies on the various forms that book censorship took in their countries.

A Project Transformed by Circumstances

Following the withdrawal of the sociologist, the project had to be abandoned in its original form, but there remained hundreds of hours of interviews with field actors that could enrich a study supplemented by other sources.

In addition to the three symposia mentioned, I had conducted research in Rome, in the archives of the Index librorum prohibitorum, partially published in 2009 (Literature and Censorship in the 19th Century), and prepared, with colleagues from my laboratory, the Centre for Cultural History of Contemporary Societies at the University of Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, an issue of the journal French Ethnology published in 2006: “From Censorship to Self-Censorship.”

Finally, the writing of the book released in 2014, titled The Regimentation of Writers: The Impossible Mission of Abbé Bethléem in the 20th Century, allowed me to accumulate a number of materials useful for illuminating religious censorship in the West from the end of the Middle Ages to the present day.

The Many Faces of Censorship

The idea of presenting a synthesis, however, faced the necessity of having documents concerning various forms of censorship, not only religious but also political, economic, and increasingly, moral and communal, emanating from human groups. It is particularly important to mention the LGBTQIA+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, Asexual) and BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) communities, who are actively defending their positions and refusing to continue being passive victims of various discriminations.

As for the censures implemented by states throughout their history, my profession as a historian provided me with multiple examples, and the organization of the National Library of France exhibition titled “Do Not Let Them Read!” in 2019, provided many more examples specific to the French context.

In the Arab-Muslim world and beyond, homosexuality is still severely repressed, as are atheism, apostasy, and blasphemy.

Economic censorships, which appeared more prominently in the 20th century and are still present in the next, received less media attention, but research on publishing around the world, from the 18th century to the present, offered numerous cases that could be easily examined. Finally, concerning the contentious notions of “political correctness,” “cancel culture,” “cultural appropriation,” and “wokism,” the literature was more than abundant, both in North America and Europe.

However, there remained an attempt to cover the Arab-Muslim world, Africa, and Asia, and here the testimony of contemporary publishers proved decisive, as did the media for all matters related to the atrocities committed as much by radical Islamism as by Hinduism and Buddhism in certain regions of the world or by evangelical currents on the American continent and in Africa.

My ambition was indeed to cover a wide range of censors to avoid any schematic or excessive focus on any particular form of desire to erase the traces of one’s enemy. Thus, to speak of the destruction of the magnificent Buddhas of Bamiyan by the Afghan Taliban in 2001 or the massive destruction of monuments perpetrated by Daesh in Mosul, Iraq in 2014-2015, I was keen to recall that Corneille’s play titled Polyeucte featured a young iconoclastic Christian sentenced to death for his zeal in destroying the statues of Roman deities.

Similarly, the legislations in force in the 22 member states of the Arab League that refuse what they call “apostasy” and “blasphemy” have as a corollary the martyrdom suffered in the 18th century, in France, by the young Chevalier de La Barre for having refused to remove his hat at the passage of a religious procession.

If comparison is not reason, as the old adage goes, placing crimes or heinous acts, committed at different times in very distant countries, in relation or perspective allows one not to yield to an essentialist reflex. To put it bluntly, Islam is no more, but no less, responsible for its transgressions than Christianity for the religious wars of the 16th century or Buddhism that persecutes the Rohingya populations in Myanmar (Burma) today.

Censorship Through the Ages

Organized thematically yet respecting chronology, the book initially presents censorship as a universal phenomenon that manifests in specific forms. It begins with religious censorship which appeared in Rome in 443 BC and was very prevalent in the West during the time when the Inquisition reigned supreme.

The book presents censorship as a universal phenomenon that manifests in specific forms.

Quebec knows this well, and its comprehensive Dictionnaire de la censure au Québec, published in 2006, offers an excellent overview of what the most conservative forces in a country can do when they are able to exercise their power or guardianship over schools, libraries, theater, and cinema.

However, political censorship remains, even today, the most widespread tool in the world, and no dictatorship, nor totalitarianism, is or has been unaware of the importance of controlling information.

Examples of the repression of samizdat authors in the Soviet Union and in the people’s democracies, the police department in Brazil during the era of Getulio Vargas, and 21st-century China with its practice of social control are reviewed. Yet, the second part also does not forget the country of Donald Trump where many states are hunting down books in school libraries, or the Francophone Catholic School Board of Providence in Ontario, which recently decided to destroy 5,000 books by pulping them because it deemed them disrespectful to the First Nations.

Morality and Social Movements: New Fronts of Censorship

The third part focuses on the moral censorships that resurged in the 1980s and have continued to expand since this sort of counter-revolution aimed at reversing the hedonism and the cult of absolute freedom of the 1960s-1970s. Naturally, this section addresses issues that are of utmost concern in North America: “political correctness,” “cancel culture,” “cultural appropriation,” and “wokism.”

While specifying that these movements initially emerged as legitimate attempts to defend the rights of minorities or communities victimized by prejudices or regressive legislation — homosexuality was not decriminalized in France until 1982 — the study also demonstrates the dead ends they can lead to.

If the “N-word” is no longer tolerable or tolerated in the United States, a country where slavery and then racial segregation have left a lasting impact on minds, in France, banning the use of the word “nègre” would mean prohibiting the reading of Voltaire’s Candide, where the chapter titled “The Negro of Surinam” ends with this relentless indictment against colonialism: “This is the price at which you eat sugar in Europe.”

Similarly, “Sales nègres,” the magnificent poem by Haitian Jacques Roumain published in the collection Bois d’ébène in 1946, could no longer call the oppressed and the damned of the earth, to use Franz Fanon’s expression, to revolt. It is worth recalling that in his most famous book, The Wretched of the Earth, the Martinican Franz Fanon uses the terms “nègre” and “bicot” without any restraint or embarrassment, convinced that the violence contained in these terms used pejoratively by the colonists can only help raise awareness among his readers. If “cancel culture” were to attack this flagship work of Third-Worldism, it would be necessary to eliminate hundreds of occurrences of these terms.

The Impact of Technology on Censorship: Current Challenges

The final part of the study focuses on economic censorships, the most hypocritical and disguised, yet arguably the most dangerous due to the dominance of the GAFAM (Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft) and the power of social networks.

The use of SLAPP suits and defamation trials massively in Canada and France against whistleblowers, the violence exerted against Julian Assange and Edward Snowden, aim solely to intimidate those who might be tempted to emulate them.

Indeed, collectives of journalists have found the appropriate countermeasures, and the publication of the “Panama Papers” was made possible by international collaborations, but large firms like Amazon, Google, Apple, or Facebook (Meta) do not intend to submit to legal obligations designed to protect individuals against the proliferation of “fake news” or sensational images.

Thus, Facebook interprets the exposure of young people to violence differently when it comes to banning the reproduction of Gustave Courbet’s painting The Origin of the World, but allowing the broadcasting of beheading scenes posted online by Daesh in the name of the freedom to inform.

Towards a New Era of Censorship: Reflections and Future Challenges

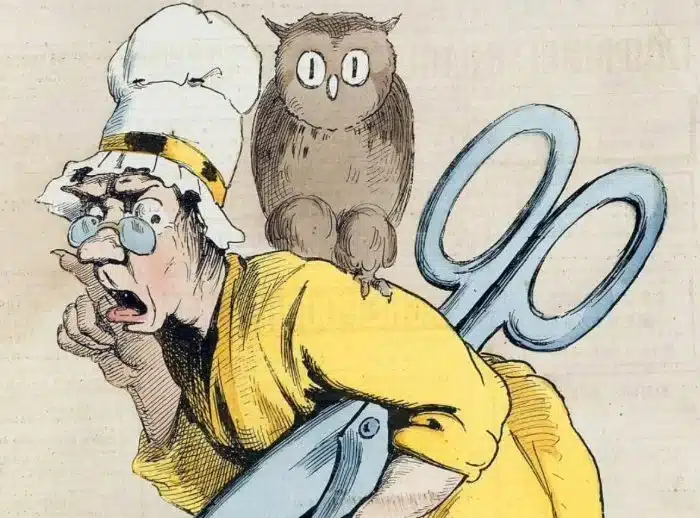

The conclusion of Interdiction de publier reminds us that censorship is a phoenix always rising anew and that if “Madame Anastasie” was depicted by the caricaturist Gill in 1874 as an almost deaf and blind old woman, holding huge scissors, it’s because she tried to emasculate all creative thought when she prevailed legally in France.

In the United Kingdom and the United States, legislation on obscenity, never well-defined, weighed heavily on writers and filmmakers until the 1960s, and, in the Arab-Muslim world and beyond, homosexuality is still severely repressed, as are atheism, apostasy, and blasphemy.

Under these conditions, authors and their publishers find it difficult to find spaces of freedom, which does not prevent Iranians from reading publications from exile publishers, or Chinese from navigating with relative ease in the web’s interstices. Associations exist, especially in North America, that help individuals and groups defend against censorship, but the book closes on a severe note, noting the resurgence of censorship worldwide.