About Digital Masquerade: Feminist Rights and Queer Media in China, by Jia Tan, published by New York University Press in 2023.

The Feminist Five and Global Attention

In 2015, Li Maizi, Wei Tingting, and three other feminists were arrested and detained for thirty-seven days in China after planning to circulate messages against sexual harassment in public spaces.

Before their detention, the five feminists and their peers had been using a series of media-related activities to advocate for what they called nüquan, literally meaning women’s rights or power.

A central question in my book is how we can theorize media activism within a context that is both illiberal and neoliberalized.

The detention of these activists, who came to be known as the Feminist Five, sparked considerable attention both at home and abroad. This included protests in Hong Kong in support of the Feminist Five, Indian feminists signing online petitions, and Hillary Clinton tweeting for them.

Marriage Activism and Digital Advocacy

On July 2, 2015, a few days after the US Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in the United States, a wedding ceremony between Li Maizi and her partner was held in Beijing. This was one of Li’s first public appearances after being released from detention. Wei Tingting, another member of the Feminist Five, hosted the wedding.

Li saw the wedding as an occasion to advocate for equal rights for same-sex couples. She called for legal reforms of marriage rights, adoption rights, and reproductive rights so these rights could be enjoyed by same-sex couples in China. The slogan they used at the wedding was “feminism demands freedom, women demand same-sex marriages.” 女權要自由,女女要結婚.More importantly, the feminists actively invited journalists to the wedding and used social media to promote this event and different notions of rights to the public.

This is one of the examples I discuss in my book, where rights discourse intersects with digital media, and feminist and queer articulations. The Feminist Five and their peers represent a community of diverse feminists nationwide, now referred to as the Youth Feminist Action School. I also explore how feminists posted altered images of their bodies online to raise awareness about intimate partner violence, and how NGOs and activists evoke and perform different concepts of rights depending on the contexts and media platforms.

Historically, feminist activism in China has been intricately linked to the state, exemplified by the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF). In comparison, the new wave of feminist activism that I explore in my book is more connected to NGOs, many of which were established after the United Nation Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995. This new wave also involves various forms of commercialized media and digital media, warranting the need for a fresh research framework.

Rights Feminism

What prompted me to write this book is the existence of two distinct media narratives about feminist and queer lives in China. One narrative focuses on repressive state oppression and the control of individuals and groups, while the other highlights the emerging neoliberal trends of liberal feminism and homonormative practices.

On one hand, China is portrayed as illiberal and oppressive, with frequent raids on LGBT commercial venues (such as bars and clubs), the cancellation of LGBT film festivals and community events, tight surveillance of feminist and queer activists, and the censorship of homosexuality in films, television, and the Internet.

“Illiberal” China is often contrasted with “liberal democratic” governments in the United States, Europe, or, more recently, Taiwan and South Korea, especially after Taiwan legalized same-sex marriage in 2019. On the other hand, the pink economy has flourished in neoliberalized China, and liberal discourses such as equal rights for women and LGBT individuals have increased.

A masquerade can be both submissive and disruptive to dominant social codes.

For instance, I discuss Alibaba Taobao’s sponsorship of gay and lesbian couples traveling to the United States to get married. While such examples can be criticized for perpetuating neoliberal homonormativity or homo-nationalism, these critiques may not fully capture the complexity of feminist and queer activism in China. A central question in my book is how we can theorize media activism within a context that is both illiberal and neoliberalized. This is not just a question for Chinese digital feminism, but for media activism in many other non-western contexts.

Another significant feature of this new wave of rights feminism and queer activism is the crucial role of digital media forms—such as digital filmmaking and distribution, social media, and e-journals—as essential platforms for feminist and queer expression. I intend to use the term ‘digital masquerade’ to theorize media activism as assemblages of embodied experiences and technological affordances within specific historical contexts. By doing so, I hope to avoid a sense of helplessness when facing censorship and other forms of control in an increasingly illiberal world.

Digital Masquerade: Between Censorship and Creativity

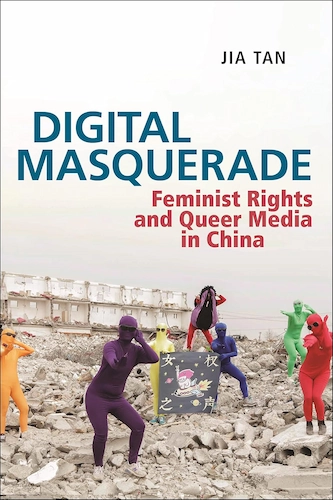

I introduce the concept of the ‘digital masquerade’ to examine the interplay between technological affordances, censorship, and the creative energy within feminist and queer media activism. A masquerade can be both submissive and disruptive to dominant social codes. I use masquerade to describe a lot of tactics used in digital feminist activism, such as putting masks and costumes to mask their identities, or altering pictures online for advocacy.

I expand the understanding of masquerade beyond individual subjectivity in feminist and queer theory to encompass the materiality of masquerade in the digital era. My usage of masquerade departs from psychoanalytic theories and focuses on assemblages of embodied experiences and technological affordances within specific historical contexts. ‘Digital masquerade’ encompasses the diverse ways in which individuals act and engage with technology in specific contexts, allowing us to move beyond the binary understanding of activism as mere conformity or resistance.

I expand the understanding of masquerade beyond individual subjectivity in feminist and queer theory to encompass the materiality of masquerade in the digital era. My use of masquerade departs from psychoanalytic theories and focuses on assemblages of embodied experiences and technological affordances within specific historical contexts. ‘Digital masquerade’ encompasses the diverse ways in which individuals act and engage with technology in specific contexts, allowing us to move beyond the binary understanding of activism as mere conformity or resistance.

Shifting Activism: From Street Protests to Online Resistance

The fieldwork I did for this book ended in 2019, and then COVID happened, preventing me from visiting mainland China. In the last five years, NGO activism, street gatherings, and the direct expression of gender and sexual rights I discussed in my book have decreased, and many people I interviewed are now living overseas.

Yet in a contradictory way, online feminist expression and organizing, as well as gay visibility, are happening on an unprecedented scale. If we only think about feminist and queer activism in China as non-confrontational, then we won’t be able to see these dynamics and sometimes contradictions. For example, the street performances of the Feminist Five and their peers I talked about in my book were non-confrontational in the 2010s, but they are not likely to happen anymore.

In another recent article, I develop the concept of slow resistance to consider feminist and queer activism in illiberal contexts. The concept of slow resistance challenges the understanding of power solely as state power and resistance solely as opposition to state power. Developing this concept within feminist activism also highlights the importance of gender and sexual politics in understanding social and political change, in which “the personal is political.”