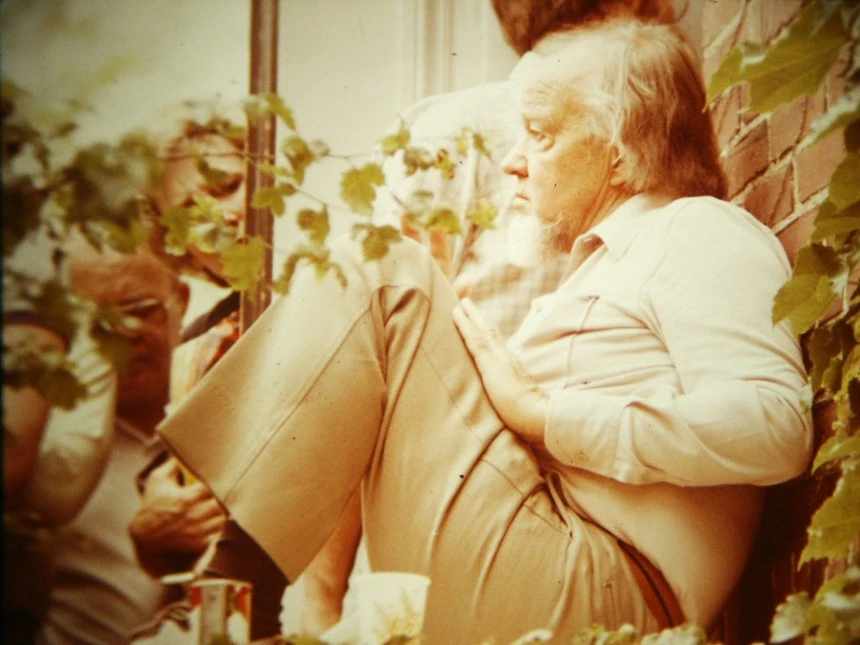

Pat Robertson and the Religious Right

After abandoning his run for the White House in 1988, famous televangelist and cofounder of the Religious Right movement, Marion “Pat” Robertson addressed the Republican National Convention in New Orleans. During his speech, Robertson listed his hopes for the nation’s future which included securing traditional Religious Right goals such as an end to abortion, supporting family morals and also realizing a healthy natural environment where “…the citizens respect and care for the soil, the forests, and God’s other creatures who share with us the earth, the sky, and the water.”

- Pat Robertson and the Religious Right

- The Origins of Christian Environmental Stewardship

- Educational Publishers and the Spread of Environmental Ideals

- The Shift towards Anti-Environmentalism in the 1990s

- Jerry Falwell and the Ridicule of Environmental Concerns

- The Decline of Christian Environmental Stewardship

- Reflecting on the Past and Envisioning the Future

The above anecdote might be surprising considering that the Religious Right is often understood as militantly conservative and in stark opposition to almost any issue supported by political left. Additionally, past scholarship has depicted the community to have either always ignored or opposed popular environmental protection efforts.

Both views of the group hold merit. The Religious Right, which is made up of a virtually all white community of conservative evangelicals and first formally organized under the group called the Moral Majority in 1979, are indeed extremely politically conservative and today are the least likely of any religious group to believe in the reality of anthropogenic climate change. Their relationship with environmental protection efforts from a historical perspective, however, proves a little more complicated than previously thought.

As my research demonstrates in The Nature of the Religious Right: The Struggle Between Conservative Evangelicals and the Environmental Movement, the conservative evangelicals who make up the Religious Right supported a theologically based eco-friendly position best called Christian environmental stewardship from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. For a variety of reasons, during this latter period, the community evolved to oppose environmental protection efforts. Thus, Robertson’s remarks at the 1988 GOP Convention were not an aberration, but at the time they neatly fit within with how the community understood its relationship with the earth.

The Origins of Christian Environmental Stewardship

The origins of Christian environmental stewardship are found in the larger national conversation regarding the following question: How much control should people have over the natural world? After World War II, the American public embraced advances of science and technology which had given humanity new powers to seemingly bend nature to its will. The “miracle” pesticide DDT, for example, had saved hundreds of thousands of service personnel during the war and afterwards chemical companies taught citizens how to apply it to crops and around the home.

By the 1950s, however, scientists began isolating DDT as the culprit for sharp drops in bird populations. Moreover, the issue led to an intense conversation in the public sphere after biologist Rachel Carson addressed the problem in her best-selling book Silent Spring published in 1962. To add to the debate about humanity’s level of control over the environment, in 1967 UCLA medieval historian Lynn White Jr. published his article “The Historical Roots of Our Ecologic Crisis” in which he blamed a Judeo-Christian mindset that, which he argued, led western nations to abuse the natural world by viewing it as simple resources for the unfettered use and benefit of humanity.

Amongst those who answered White was Francis A. Schaeffer, an increasingly popular author within the conservative evangelical world. During in-person lectures Schaeffer explained his theological environmental views that were ultimately published as a book in 1970 titled Pollution and the Death of Man: The Christian View of Ecology. Here he argued that people should treat the earth with respect because it was created by God and therefore it should be elevated in value beyond simple resources for financial gain. He additionally said of capitalism that entrepreneurs deserved “some” profit, but must not abuse the earth. He specifically stated that Christians must practice a “limiting principle” in their control over the natural world.

Educational Publishers and the Spread of Environmental Ideals

Schaeffer’s views, perhaps best described as Christian environmental stewardship, quickly became widely accepted within the conservative evangelical world and circulated throughout the communication network that would later play a role in creating the Religious Right movement. These venues included magazines such as Christianity Today, Moody Monthly, Eternity, and the Christian school educational publishers of A Beka Book and Bob Jones University Press. These latter two presses originated in response to the home and Christian school movement that largely began in response to the early 1960s Supreme Court rulings that banned prayer and Bible reading in public schools.

If the community once held eco-friendly views, they could in theory hold them again.

This situation combined with worries about school integration and wanting a safe space from late 1960s counterculture influences led not only to parents placing their children in home or Christian schools, but also looking for new educational material that would be used in their classrooms.

The fundamentalist schools, Bob Jones University (Bob Jones University Press) and Pensacola Christian College (A Beka Books or Abeka since 2017) stepped in to give the parents what they wanted.

Analyzing the material for home and Christian schools is particularly important because since their founding in the mid-1970s, the publishers structured ideologies including Christian nationalism that would function as the founding principles for the Religious Right movement. Simultaneously, however, the same publishers also repeated the lessons of Christian environmental stewardship throughout the 1970s and 1980s. As late as 1989, for example, A Beka Book published an economics textbook that directly told students people must curb profits and in other words follow Schaeffer’s “limiting principle” for the betterment of other people and nature.

As the author wrote, “The short-run costs of pollution prevention, conservation and urban restoration are high. Yet the long-run costs to humanity neglecting those economic responsibilities would be far higher.” The text went on to advise, “An economy that fails to provide for future generations (by using up resources) is like a farmer who consumes his own seed-corn intended for next year’s planting.” A year earlier, Robertson shared similar eco-friendly sentiments during the GOP National Convention.

The Shift towards Anti-Environmentalism in the 1990s

The catalyst stimulating a rise in popular anti-environmental views proved to be in response to growing excitement surrounding the twentieth anniversary of Earth Day in 1990 and perhaps more importantly the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. In parallel with these events, the multi-million-member National Association of Evangelicals dedicated an entire issue of their magazine United Evangelical Action to support Christian environmental stewardship.

At the same time, the larger Southern Baptist Convention dedicated an environmental seminar towards stewardship in March 1991. For the moment it seemed the white conservative evangelical community was on its way to turn the long-held eco-friendly ideas into action.

To curb this momentum, secular conservative think tanks like the Free Enterprise Institute and special advocacy groups including the far-right John Birch Society increased anti-environmental information causing a surge of resistance against the international push to stop anthropogenic climate change. As sociologists Arron McCright and Riley E. Dunlap demonstrate, these groups produced the following three core arguments throughout the 1990s:

- Climate change is not happening.

- If it is, then it will be beneficial.

- Any action will ruin the economy.

These three arguments made an impact amongst American conservatives in general, and crept into the conservative evangelical community. By 1990 Robertson had turned his back on Christian environmental stewardship as did Christian and home school educational material publisher A Beka Book in 1993. For the first time the press released a science textbook for middle schoolers that parroted the messages from the think tanks and additionally assured the reader not to worry about the environment because God would take care of it. In a dismissive and flippant way the authors encapsulated their position through the following poem: “Roses are Red, Violets are Blue, They both grow better with more CO2.”

Jerry Falwell and the Ridicule of Environmental Concerns

The arguments against Christian environmental stewardship were wide ranging, but usually connected through the tone by which they were delivered. Like the textbook for middle schoolers, the messages overall simply asked fellow conservative evangelicals to ignore caring for God’s earth or risk being laughed at for believing in a delusion.

By roughly 1994, Christian environmental stewardship was gone as an established and accepted position amongst conservative evangelicals.

Robertson’s fellow cofounder of the Religious Right, Pastor Jerry Falwell was particularly adept at this approach. On a Sunday morning in May of 1992, for instance, Falwell framed environmental issues as laughable hysterics to his 30,000-member congregation. “Boy,” he said, “they’re talking about global warming. The disappearance of the ozone layer. They got me under convictions (about) putting hairspray on my head!” The audience erupted into laughter.

He continued by promising that although he valued nature, actively protecting it was ridiculous. “But these tree huggers who want to save the snail darter and the spotted owl and who want to save the whale and demonstrate outside the fur stores, they don’t want any more fur coats and those hypocrites go right across the street to McDonalds and eat a hamburger. Where do they think that hamburger comes from?”

After the laughter subsided, the tone became serious as he compared the importance of stopping abortion to protecting nonhuman nature. “You want to save those snail darters, spotted owls and whales and other furry animals. How about those babies? You hypocrites. Shut your mouth.” The congregation responded with solemn “amens.”

In his sermon Falwell portrayed environmental concerns simply as ridiculous and something to be automatically discounted. He first framed the connection between hairspray and the ozone as hysterics by considering the issue of CFCs in aerosol sprays that contributed to the breakdown of the ozone layer as a laughable delusion. He then immediately accused environmentalists with the illogical hypocrisy of wanting to save “furry animals” while eating a hamburger.

Such weak-minded people, he insinuated, merited immediate dismissal as any hysteric deserved along with a dose of laughter. Through this framing device, Falwell helped transform growing compassion for the environment into a category that no one in his congregation wished to be identified with. Although Falwell did not invent this approach, it was this method of simple rejection couched in the forceful vehicle of ridicule, which was utilized in the early 1990s to turn white conservative evangelicals against their theologically supported eco-friendly views.

The Decline of Christian Environmental Stewardship

By roughly 1994, Christian environmental stewardship was gone as an established and accepted position amongst conservative evangelicals and unto the present day it remains an object of derision. The approach seems salient within conservatives in general. In Strangers in their Own Land, sociologist Arlie Russel Hochschild tells of her interactions with Mike Schaff, a staunch rightwing conservative who considers himself religious, but not a church goer while also being an environmental activist out of necessity.

The conservative evangelical community has overwhelmingly voted for climate change denier Donald Trump in both the 2016 and 2020 elections.

His environmental concerns grew from a local accident in 1980 known as the Bayou Corne Sinkhole. In this instance, the Texaco company drilled into Lake Peigneur in Louisiana perforating a salt dome that caused a reaction so large that it sucked down “…two drilling platforms, eleven barges, four flatbed trucks, a tugboat, acres of soil, trees, trucks, a parking lot and an entire sixty-five acre botanical garden.”

This disaster combined with a host of other environmental problems have caused some local residents to relocate and others like Schaff, who refused to leave, to think deeply about the relationship between his conservative political identity and the environment of which he understands in a category connected with embarrassment. As he told Hochschild, “A lot of people think the environment is a soft, feminine issue.” Such an identity he finds humorous stating, “‛This is the closest I’ve come to being a tree-hugger.’ He tells me (Hochschild) with a rueful smile.”

Schaff’s views of environmental protection makes sense. Since the early 1990s, people like Falwell consistently framed environmentalists as hysterical “tree-huggers” who more than deserved ridicule through rounds of laughter. Such a perception is hard to hold onto, however, when witnessing the environmental problems that literally enveloped Schaff’s surroundings.

Reflecting on the Past and Envisioning the Future

In closing, this history explaining the evolving relationship between conservative evangelicals and the environment not only asks us to revise how we understand the past, but perhaps also suggests a hopeful future. It posits that if the community once held eco-friendly views, they could in theory hold them again.

After all, Schaeffer’s 1970 Christian environmental stewardship idea was supported through theology and it did become the accepted viewpoint amongst conservative evangelicals for more than two decades. It is difficult, however, in today’s politically polarized climate to believe it could somehow make it back to the support it once enjoyed.

The conservative evangelical community has overwhelmingly voted for climate change denier Donald Trump in both the 2016 and 2020 elections (by 77 to 84 percent). With this in mind, it is hard to imagine a future GOP candidate endorsed by the Religious Right similar to Robertson who once told voters he wanted a nation where nature is respected because it “shares” the earth with humanity.