Introduction and Overview of the Book

Alvin Cheung: Professor Davis, thank you very much for agreeing to this interview. You’ve recently had a book published, Freedom Undone: The Assault on Liberal Values and Institutions in Hong Kong. So perhaps we could start with you giving us a brief overview of the book.

- Introduction and Overview of the Book

- The Cycle of Mistrust and Intervention

- The Limits of the Basic Law

- Parallels with Tibet

- Impact of the National Security Law

- Comparative Law and Its Use

- The Illiberal Turn in Judicial Decisions

- The Hong Kong 47 Case

- Injunctions and Freedom of Expression

- Article 23 Legislation: Old vs. New

- International Dimensions and Repression

- Supporting Hong Kong Activists Abroad

- Is Hope Lost? Grounds for Optimism

Michael Davis: Yes, I’ll try to keep it simple. The book has essentially two missions. One is to look at the assault on liberal values and institutions as a phenomenon that’s part of China’s national security policies. Such policies are motivated by the Communist Party’s view that liberal values and institutions are a threat to party rule. I quote Chow Hang-tung’s statement from prison arguing that what is happening in Hong Kong is not merely an anomaly, but a warning. This speaks to people interested in the illiberal agenda of China and Russia.

The book traces contentious issues, massive protests, and official policies that slowly and then rapidly squeezed and degraded the city’s liberal institutions.

The second mission of the book, the largest part of the text, is to interrogate what has happened in Hong Kong, to look in some detail at how this illiberal turn has taken shape over time and what it has meant to Hong Kong people. The book offers a critical narrative history of what has happened in Hong Kong from the handover forward, looking at both the massive protests and the reactions of both the mainland and Hong Kong governments.

As a foundation, I argue in the book that you can’t really understand the Sino-British treaty or the Basic Law except as liberal documents, with their heavy emphasis on liberal human rights, the rule of law, and democratic development. Hongkongers, in their wisdom, understood and promoted the promised democracy because they thought a government that was more directly answerable to the people would better guard Hong Kong’s core values and institutions.

The book, through all the periods from the handover forward, traces contentious issues, massive protests, and official policies that slowly and then rapidly squeezed and degraded the city’s liberal institutions. Various chapters are set in different periods exploring what happened, the reasons for protest, and the government’s response.

These interactions produced a dialogue between the people and the Hong Kong government, and sometimes the Beijing government, over 20-plus years. Several chapters focus on the National Security Law and its implications, followed by a chapter on the so-called patriots-only elections that Beijing imposed, with a glance finally at the Article 23 legislation proposed in a consultation document just before publication. In combination, these developments offer a textbook example of how freedom was undone.

The Cycle of Mistrust and Intervention

Alvin Cheung: We’ll come back to some of the more recent developments in a little bit, but one of the major themes of the book -and it’s one that you mentioned just now- is this downward spiral in which Beijing’s mistrust of Hong Kong leads to heavy-handed interventions that in turn generate public and pan-democratic pushback, that itself creates yet more mistrust on the part of Beijing. There was a repeated cycle of this stretching over the past 20-odd years. Was there ever a point, looking back, when that cycle could have been broken?

Michael Davis: Early on it could have. It would not really have gotten started if the government had stuck firmly to Basic Law commitments. Early on there was the so-called right of abode case.

The Court of Final Appeal ruled that the applicant children of Hong Kong residents living on the mainland had a right to live in Hong Kong. The government didn’t like the ruling and went around the court to Beijing to get an interpretation. In doing so the government effectively used its Beijing connection to override the court.

This posed a threat to the rule of law and judicial independence and would hang over the courts going forward. The government next in 2003 tried to impose national security legislation under Article 23 of the Basic Law, an article requiring Hong Kong to enact such legislation “on its own.” A proposed bill raised human rights problems. Several of us legal experts formed the Article 23 Concern Group and voiced our concerns.

We argued that the spirit of the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Basic Law was to maintain a liberal order in Hong Kong. The text of the Basic Law firmly committed to maintaining the rule of law and judicial independence. The further inclusion of 16 fundamental rights—half of which relate to free expression–and the ultimate aim of universal suffrage left little doubt in that regard. Anything less would not have allowed Hong Kong to thrive.

Our efforts and the pamphlets we released on the streets of Hong Kong led eventually to massive protest.

Any diminution of that in the Article 23 proposal, through increased police powers, media oversight, or excessive restraints on organizations, would have undermined that liberal order.

Of course, much more severe restraints two decades later were imposed in the recent Article 23 legislation enacted in 2024. But at the time, for one of the most liberal and open societies in the world, there was great concern. In 2003, when protests were still allowed, our efforts and the pamphlets we released on the streets of Hong Kong led eventually to massive protest.

The government eventually backed down, but its initiative alerted Hong Kong people to the need for democracy if the commitments in the Basic Law were to be maintained. At that juncture, if the government had taken a different direction, we probably would have seen an Article 23 bill that was reform-oriented, that was progressive and geared towards maintaining Hong Kong’s human rights and freedoms. We didn’t see that.

These two events signaled that the government would be taking a hard line going forward. In 2004, when Hong Kong people took to the streets to demand democracy, a very large protest again, the government did not give in, and the die was cast for a hardline approach going forward. As I discuss in the book, we hit a pattern of the government promoting some hard-line agenda and the people responding with protest, a pattern that would repeat itself going forward.

The Limits of the Basic Law

Alvin Cheung: A couple of things you touched on in that answer are limits–or kill switches, if you like–that were baked into the Basic Law. There were limits on judicial authority in the form of the National People’s Congress Standing Committee having the power to interpret the Basic Law. And there were limits on the case and scope of democratic reform. Despite those rather significant limits, when you ask in the title of Chapter 3 whether the Basic Law was an enlightened commitment or a ruse, you seem to still think it was an enlightened commitment and that there was at least some sort of desire to make good on the more enlightened provisions. Why is that?

Michael Davis: I think in those days when the Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed, and the Basic Law enacted there was still some residue of China’s reform agenda that had been launched by Deng Xiaoping. This agenda had flowed into the Basic Law drafting process. Despite such an agenda, two basic flaws reflecting Beijing’s long-established system of control would remain in the Basic Law.

One is the judicial review element, which I discuss in the book, as you have mentioned. The other was foot-dragging over democratic reform. On the latter, the government would invoke language in the Basic Law calling for “gradual and orderly progress,” which essentially meant no progress.

The 17-point agreement was a precursor to the “one country, two systems” model applied in Hong Kong.

There was a sense that if the Hong Kong government showed more restraint, which it had not shown in the right of abode case, and Beijing also is somewhat restrained in avoiding interpretations of the Basic Law then the liberal order might survive.

In hindsight, this may have been wishful thinking but at the time, in China’s reform era, there was hope.

There was hope that Beijing would show restraint and possibly move toward greater liberal reform and the Hong Kong government would find its voice to represent Hong Kong people. Neither ultimately proved true, but that was the popular sentiment at the time.

Parallels with Tibet

Alvin Cheung: One of the more curious parallels that come up in the book early on is this idea that One Country, Two Systems was modeled on the 17-article agreement under which China took control of Tibet. And when we spoke yesterday, you briefly also referred to Tibet. It’s interesting.

The journalist Ching Cheong wrote something for Radio Free Asia where he said that round about the time the Joint Declaration was being agreed, he was told by a senior former Chinese spy in Hong Kong to pay close attention to the 17 Tibetan articles, perhaps in a hint that he should not be overly optimistic about the future of Hong Kong. So perhaps you could say a little bit more about what you see as being the parallels between the Hong Kong arrangement and the Tibetan arrangement.

Michael Davis: In the Tibetan agreement, the commitment wasn’t to a liberal constitutional order, but rather to local autonomy and the continuance of governance by Tibetans themselves. And of course, that proved a false hope.

I have had many occasions to work with Tibetans in exile on trying to understand Beijing’s policies towards Tibet. In those early years after the Joint Declaration and the Basic Law, there was a move within the Tibetan exile community to gain a model like Hong Kong for Tibet. An important distinction for the Basic Law was an article that specified that mainland departments were not to interfere in Hong Kong affairs.

The downfall of the 17-point agreement was excessive interference by Chinese mainland officials, as is now the case for Hong Kong. The Dalai Lama fled into exile in the face of such excess. So yes, the 17-point agreement was a precursor to the “one country, two systems” model applied in Hong Kong.

The so-called special autonomous regions in mainland China have virtually no autonomy at all.

It also represented a kind of threat that the same would happen in Hong Kong, which is now the case. But that downfall did not fully materialize for 20 years. Tibetans even produced their own memorandum on genuine autonomy in 2008 in response to efforts to talk to mainland leaders. They asked for something akin to what Hong Kong then had, though in a more limited sense.

They didn’t imagine they could get a full liberal constitutional order so they demanded less. What Tibet has now is autonomy in name only. The so-called special autonomous regions in mainland China have virtually no autonomy at all. Rather, the ones in the periphery regions are under greater control of the central government than ordinary areas like Shanghai and elsewhere.

China has used the notion of autonomy more as a national security concept to control regions which they view as threatening, due to alleged separatism and so on. Hong Kong has now been placed in such a category. Many people ask if Hong Kong is becoming another mainland city? Perhaps rather it is becoming another region like those peripheral regions of Xinjiang and Tibet? It has the same ingredient of causing Central Government concern about national security.

Impact of the National Security Law

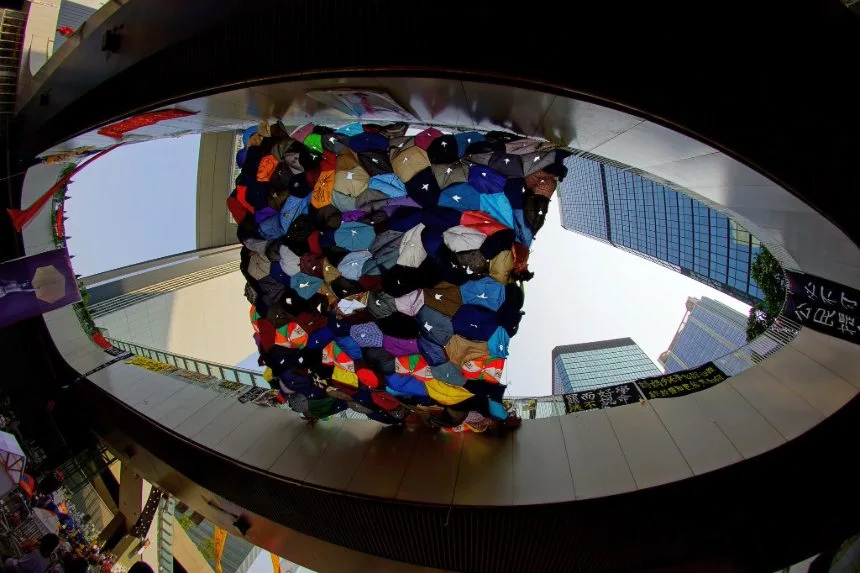

Alvin Cheung: One of the things that I used to say about “One Country, Two Systems” is that there’s more than one mode of failure. It’s not true that the only mode of failure is Hong Kong ends up looking like any other mainland city. There were supposed to be specific commitments as to what the second system looked like. So now of course that seems to have become moot in light of the 2020 National Security Law (NSL) and its aftermath. So I want to talk a bit more about the NSL and its aftermath now. Why do you think the 2020 crackdown has been so effective and what elements of the crackdown stand out to you in particular?

The NSL further aims to change people’s minds through education by controlling and imposing all kinds of guidelines that aim to silence teachers and students.

Michael Davis: Well, that is of course one of the big missions of the book, and three chapters go into this at great length. The NSL, a direct imposition by Beijing, reflects a comprehensive crackdown. It disregards any reasonable interpretation of what the Basic Law requires in regard to Hong Kong’s autonomy; that’s more or less thrown out the window. It imports the mainland national security regime to Hong Kong.

Four years later in the consultation document over Article 23 legislation the government makes explicit its wholehearted embrace of the mainland national security regime under the label of a “holistic approach,” It describes this at some length in the consultation materials for the Article 23 legislation. So that’s not ambiguous, but really in 2020, that was already done. The biggest difficulty with such national security regime is that it’s unclear what is prohibited and what is not.

The NSL is effectively a textbook on how to suppress an open society.

This requires people who don’t want to risk arrest to make a wide berth for national security. These features combine to provide the Hong Kong government with all the tools it desires to control opposition in Hong Kong.

The list of ways it undermines human rights and the rule of law is long: the NSL was imposed on Hong Kong by the Central Government without consultation; the NSL is expressly superior to all local laws; it is effectively an illegal amendment of the Basic Law; It’s not subject to constitutional judicial review; it has a select panel of judges who we saw operating this week in regard to the 47 democrats case; and most importantly, it has a local Committee on Safeguarding National Security whose behavior is not subject to judicial review.

The result is that the whole national security apparatus imposed under the law can be done in the dark, in shadows, with us only hearing about it when someone’s finally arrested. Added to that is an Office for Safeguarding National Security. This office is staffed with mainland public security and state security officials. The utter comprehensiveness of the regime makes it very dangerous for anybody to speak out. It doesn’t stop there. We often read in the news about the criminal justice elements, and they are important in degrading in many ways the common law approach, offering a further list of process failings.

These include taking away people’s presumption in favor of bail, making it effectively a presumption against bail; designating a select panel of judges to hear NSL cases, as we see in operation again this week; and denying the right to a jury, with a three-judge panel replacing a jury. In these changes very fundamental ingredients of the common law protections of due process are taken away or degraded. Beyond criminal justice the NSL tries to transform the society by targeting regulations and administrative control of the media, education, and social organizations.

In particular, RTHK, the prominent public broadcaster modeled on the BBC, is now subject to guidelines that control and affect what it can report on and how it reports, severely muting any official criticism. That has a big impact on public access to information. The NSL further aims to change people’s minds through education by controlling and imposing all kinds of guidelines that aim to silence teachers and students.

Exceptional justice has a very checkered history.

The NSL is effectively a textbook on how to suppress an open society. That is why the warning notion is very important.

The NSL is not just railing against liberal values but is providing absolute replacement of all the liberal institutions that were there or by transforming them to a point where they’re unrecognizable. This is why we now have free speech silence in Hong Kong.

Alvin Cheung: I just want to add to your point on the vagueness of the NSL being a feature and not a bug. It reminds me of Perry Link’s now very old article, The Anaconda in the Chandelier, where his point was precisely that the mainland criminal justice system derives its power from its vagueness.

Michael Davis: It offers a brazen combination of vagueness on the one hand and comprehensiveness on the other. The language is vague, but the tools in the government’s hand to suppress you are comprehensive. The Office for Safeguarding National Security isn’t even subject to local jurisdiction, let alone judicial review. All constitutional safeguards are degraded.

The government argues that every country has national security laws. While every country has them, they may not be so vague or lacking in safeguards. In a liberal democracy, even where such laws are sometimes vague, they’re subject to constitutional limitations. When you take that away, it doesn’t matter what the language is, you don’t have sufficient rights protection.

Comparative Law and Its Use

Alvin Cheung: You bring up an interesting point there in terms of the use of comparisons, the strategic use of comparisons by officials, and I would suggest by judges, where on the one hand you have Hong Kong officials trying to defend the NSL and now the safeguarding national security ordinance, the Article 23 legislation, by saying, well, every jurisdiction has national security legislation. But on the other, as you point out in your book, there are judgments where counsel have tried to argue that, for instance, as a matter of common law, sedition has these required elements as to intention to incite disorder or some sort of violent uprising.

And the response from the government and sometimes even the courts is that there are unique conditions in Hong Kong that mean that these precedents from the rest of the common law world don’t apply. So there’s a very interesting schizophrenia that’s happening in terms of the use of comparisons between jurisdictions. I wondered if you could say a little bit more about how you think comparative law is being used and abused as part of that process.

Michael Davis: Right. Officials, most recently, in the draft of the Article 23 legislation, are saying the UK and Australia, and Singapore have similar laws. Well, the question I already raised is whether they have the institutions to guarantee that the laws function in a way that protects rights and due process. That’s the failure of their argument.

Those institutional checks are missing. A recent 300-page written verdict on the remaining defendants in the 47 democrats’ case did not once mention human rights. I wrote one of the pamphlets in 2003 for the protest, the so-called rainbow pamphlets. I cited the Johannesburg Principles’s requirement, that a speaker must intend imminent violence, and imminent violence must be likely to occur. In common law cases like the U.S. case of Brandenburg v. Ohio, this limitation is expressed with slightly different words, that the speaker intend imminent unlawful action and that it be likely to occur.

Distrust of judges has inspired select judges to be more accommodating in their judgments, trying to distinguish the Hong Kong situation as exceptional.

But this kind of language now is dismissed or ignored in the Hong Kong courts. One relevant judgment said, in effect, these standards in the Johannesburg Principles and the Siracusa Principles are outdated. And then they invoked something called exceptionalism, that Hong Kong’s an exception. If anybody knows anything about history, we know that the purveyors of the terror in France over 200 years ago talked about exceptional justice. So exceptional justice has a very checkered history.

Such is the tool of autocrats when they want to repress people. And it’s sad to hear such approach being used by our courts in Hong Kong, because Hong Kong courts have long been respected for their purposeful approach to human rights. And of course, this is why in the National Security Law Beijing required that there be select judges, because Beijing obviously didn’t trust all Hong Kong judges to go along with what Beijing wants in regard to how the National Security Law or similar laws regarding national security are applied in Hong Kong.

They put in place a regime to designate select judges, and they further have a provision to dismiss them from the select list if they make statements that offend national security. Of course, they don’t tell us who’s on the list. We only get that from watching cases. This distrust of judges has inspired select judges to be more accommodating in their judgments, trying to distinguish the Hong Kong situation as exceptional.

The Illiberal Turn in Judicial Decisions

Alvin Cheung: Speaking of the illiberal turn in recent judgments, did this happen overnight? Did this only really begin with the imposition of the NSL, or were there rumblings of this sort of illiberal turn beforehand with things like the express rail judgment?

Michael Davis: I remember long ago when I was a student at Yale Law School, an argument was made that judges are people too, just like in the brand Toys R Us, judges are us. And they have a finger they can stick in their mouth and hold to the wind to feel which way the wind is blowing and try to accommodate the pressure that that represents.

And a good judge will try his or her best to be conscious of society and the forces going on in society and not dismiss them entirely but try to safeguard the fundamental rights of society and the rule of law at the same time. This is called legal realism, as you know.

The influence of power and those in power and the society at large on the judiciary is something that’s recognized. As the governments in Hong Kong and Beijing became more and more intrusive in Hong Kong, we will see some efforts by the judiciary to accommodate that. Some limited amount of that is okay, because there’s some need to safeguard their position.

If they go too aggressively against an autocratic regime, they might be slapped down. They do feel official pressure. That pressure increased dramatically with the imposition of the National Security Law—well beyond acceptable bounds in an open society. There is now real concern that the courts will too readily succumb to such pressures.

The Hong Kong 47 Case

Alvin Cheung: To return to the more recent illiberal judgment, the case about the 16 members of the Hong Kong 47 who pleaded not guilty, how do the Hong Kong 47 fit into the broader story you tell? I know there’s a chapter where you talk about the gutting of electoral arrangements for the legislature and district councils, but how specifically does the primary case fit into this bigger picture?

Michael Davis: It’s actually an interesting paradox. There’s a serious irony in the final outcome of that case. Conducting a primary, as was part of the case to prove conspiracy, under the guarantees of the Basic Law should be perfectly legal. It’s a way to select the better candidates within a political camp where there’s too much competition. In fact, it’s a common practice in democracies.

After a primary and election the democrats had a goal to push the government to adopt the five principles from the 2019 protest, which are themselves also very legal in Hong Kong. There’s nothing illegal about investigating police behavior or releasing people that have been arrested and so on, or carrying out the promised universal suffrage, which was the fifth demand.

All of their demands are perfectly legal. And then they planned to put pressure on the government to do that by using another article in the Basic Law which says that if the budget is rejected, that there’s a stepped process where eventually the Chief Executive could be forced to resign. The irony in the verdict the other day is that the government, which has actually undermined the independence of the judiciary and totally tamed the legislative council, with its independence degraded, is prosecuting people who are actually using the Basic Law provided legal structures to defend the core elements of the system.

And I suppose no one is going to miss this irony that the people who actually overthrew the existing constitutional order are the ones prosecuting people who were trying to defend it. The book has a chapter that talks about the patriotic election regime and how it has all these different elements that essentially block any genuine opposition candidate from even running for office, through a vetting process.

It works to effectively assure only people who support the government’s policies are able to clear all the hurdles to run and be in the legislature. The government first overthrew the due process regime in national security cases, and then they subsequently overthrew the legislative regime. And now they put the courts under severe strain. One may wonder who’s guilty of subversion here, those who overthrew the constitutional order or those who defended it, but unfortunately the result is going to be severe for these defendants.

Injunctions and Freedom of Expression

Alvin Cheung: Turning to another recent judgment, and you mentioned the earlier judgment in the book where the Court of First Instance refused to grant an injunction against the dissemination of “Glory to Hong Kong” on online platforms, including YouTube. And one of the reasons the court gives was, well, the government already has all these criminal law powers. Why on earth is it seeking an injunction? The Court of Appeal overturned that refusal and granted the injunction. Does that surprise you? And what does it portend for critical expression online?

Michael Davis: It doesn’t surprise me. What we’re talking about here is something that is especially guarded against when it comes to free speech doctrine: prior restraint. Freedom of speech is not absolute. There are restrictions that pass the test in terms of protecting basic freedoms. But prior restraint is something that has always been an anathema for courts in dealing with free speech.

All social media in Hong Kong is at risk in ways that it has never been before.

The Court of First Instance’s original ruling made a lot of sense. The Court of Appeal of course, goes where the government wants it to go for the very reasons we’ve already discussed, with all the pressure on the courts. There’s an urge to accommodate the government, especially in the area of national security.

Even in the cases of prosecution, if the government brands something a national security matter, then it seems the court just accepts that. So that’s why you hardly see any reference to free expression at all in cases which around the common law world always involve free expression.

This gives the government clearance to target other publishers of information. And in this age of social media, there are all sorts of publishers of that type which are now vulnerable. This puts all social media at risk in Hong Kong in ways that it had never been before.

Article 23 Legislation: Old vs. New

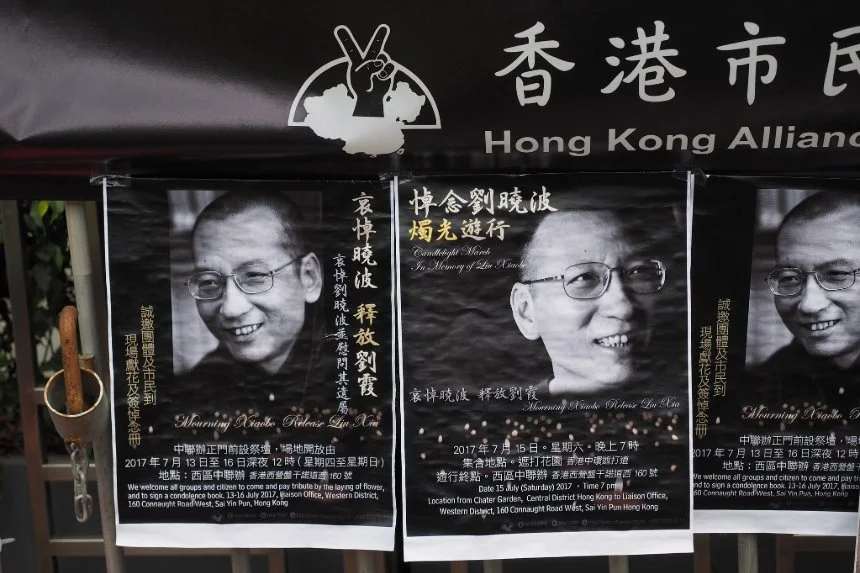

Alvin Cheung: Speaking of Article 23 national security legislation, you do refer in your book to the consultation document, and the legislation since passed in record time. It was used just days ago to arrest Chow Hang-tung again, and six others for posting allegedly seditious messages in the run up to June 4th. You’ve mentioned being in the original Article 23 concern group. So first of all, can you give us a flavor of how far apart the old and new legislative proposals were? And then perhaps you could go on to say a bit more about how the new legislation affects the overall assessment you give in your book.

Under the new Article 23 legislation, the offence of sedition adopts the vague and extreme colonial language of causing hatred in society.

Michael Davis: I would say to the first part of your question, the differences are breathtaking. The original 2003 proposals were defective at a time when there was a strong commitment to basic freedoms in Hong Kong. The government was under pressure to sustain that commitment to inspire confidence in Hong Kong, both locally and internationally. The things we fussed about, like more police powers, some limitations on organizations, and a few other things, were in the context where the bill should have been a reform-oriented bill.

Hong Kong already had laws on a lot of the topics that are covered by Article 23. Those colonial laws were draconian in their content, regulating in relation to sedition, inspiring hatred, and things like that. But the colonial laws in the age of the Hong Kong Bill of Rights, like the sedition law, were not used. They ceased to be used, as is common in a common law jurisdiction, when it was judged that they were not going to withstand constitutional scrutiny. Sometimes such laws remain on the books. If the government attempts to use them, then they can be stricken by the courts exercising constitutional judicial review.

But nonetheless, those laws existed, and the expectation at the time was that Article 23 legislation would be reform-oriented, up to date in the context and adhere to international standards, as well as guarantees made in the Basic Law. The new 2024 Article 23 legislation is way, way, way beyond all of that. There’s little or no regard for basic freedoms in this new model.

It is not the case of an open society attempting to provide national security legislation, but something very much in the mode of an autocratic regime. As I highlight in the book, the consultation document already told us where they were headed. They were headed towards adopting the mainland national security regime, which they later praised in the first chapter of the Article 23 consultation document.

The mainland regime views national security threats as primarily internal, coming from the Chinese people, with less emphasis on external threats, though they often accuse local activists of being influenced by foreign forces. The mainland leaders have read the political economy literature, and know that when a society achieves a certain level of economic development, people will start demanding greater freedoms and the rule of law.

Their national security regime, which targets 20-plus areas of society to be monitored and watched, is very much oriented towards making sure the Chinese people do not overthrow the Communist Party. It aims to protect Communist Party rule. The Hong Kong consultation document makes explicit that the Hong Kong government admires that mainland approach. Its so-called comprehensive national security concept is adopted as a holistic approach. By the time the consultation document was issued, we knew where it was headed. Such embrace is its defining characteristic. It’s very expansive in terms of state secrets.

For example, anybody who comments on official policy on the mainland risks intruding on state secrets. And everybody is a guardian of state secrets. In most common law practice, it’s imagined that officials have secrets and they’re not supposed to reveal them. But on the mainland, if I dig up something that’s going on officially, even if it’s just economic or social welfare policy, then it could be a state secret and I could face arrest and punishment. So that approach is now adopted to Hong Kong, specifically citing similar areas of social and economic development as are targeted on the mainland.

Among the areas covered, espionage includes a wide range of behavior that would be protected in an open society. Espionage is defined as “obtaining, collecting, recording, producing, or possessing, or communicating to any person, any information, document, or other article that is or is intended to be for the purpose useful to an external force.”

So virtually any kind of diplomatic work to try to gain information on the country that’s hosting them could be included. Likewise, journalistic research on social and economic development is expressly targeted. This partakes of the same problem of the NSL’s vagueness. You and I don’t know when we’re crossing the line. So what do we do? We don’t talk about it at all. We stay away. The law also aggressively targets foreign interference in any form.

The people convicted this week in the 47 democrats’ case are accused of having the intent to endanger national security. The judge indicates that even if they did not know they endangered national security, they could have the intent to do it. How can you intend to endanger national security when you don’t know the boundary of national security—a breathtaking vagueness? Under the new Article 23 legislation, the offence of sedition adopts the vague and extreme colonial language of causing hatred in society.

A lot of the Article 23 legislation talks about collusion with external forces. It forbids any work with a foreign or international organization with political ends.

If I make an argument with passion, will I cause hatred in society? Politicians today are causing a lot of hatred in society around the world. In a related area, the NSL has new regulations relating to computers, which risks heightened surveillance. What you download could get you in trouble. What does this say to anyone traveling to Hong Kong?

In the old days, we used to suggest that academics and some business people bring a burner phone, and a burner computer to Beijing. The NSL now suggests that similar advice may likewise apply to Hong Kong. Some companies with overseas offices are now separating their computer networks so that the Hong Kong company is not inside their international computer system, putting the local office at risk.

A lot of the Article 23 legislation talks about collusion with external forces. It forbids any work with a foreign or international organization with political ends. What do we do as academics? Can foreign institutes safely host Hong Kong academics in sensitive areas? If that institute is focused on political change, democracy, or development is there a risk to them to be working with your institute? Again, the vagueness element kicks in.

I found it very interesting in the consultation document that they have language where they criticize anybody who takes these kinds of actions under the “guises” of fighting for human rights or monitoring human rights. So now fighting for human rights and monitoring human rights are labeled as guises. They’re not genuine. This suggests that human rights advocacy is illegal. And I think that’s the kicker at the end of it all. Yes, the difference between the 2003 bill and the current one is breathtaking.

International Dimensions and Repression

Alvin Cheung: Speaking of this issue of collusion with external forces, it seems like part of the current crackdown is aimed at simultaneously isolating Hong Kong activists from their overseas counterparts while also engaging in transnational repression. So can you say a bit more about the international dimensions of the crackdown as well?

Michael Davis: Yeah, it’s very obvious. The bounties and arrest warrants targeting human rights advocates are widely reported. Vagueness lifts its ugly head again here because we don’t know who else is being targeted other than those who have been named. Many people who have not been named are doing the same kind of human rights advocacy as those who have been. After years of advocacy both in Hong Kong and now from overseas in my writing and public comments, I doubt it is safe for me to go back to Hong Kong.

There’s a huge element in the Article 23 legislation to target any support for overseas activists.

Perhaps you question that as well? This is the design of international repression. Under the new law, you’re supposed to report somebody who’s engaged in treason at the risk of arrest if you fail to do so. But you likely do not know precisely what treason is. If you don’t report them, then you could be sentenced to jail. There’s a huge element in the Article 23 legislation to target any support for overseas activists.

The aim is to make it risky to communicate with them and to thereby isolate them. The Hong Kong government, just as I am speaking with you, just canceled the Hong Kong passports of 6 activists in Britain, while emphasizing that any support for them will be treated as a crime, again to further isolate them. And at the same time, we know from reports that agents of the Hong Kong and Chinese governments are following and harassing overseas exiles. I was just in the UK when there were arrests of alleged Hong Kong government agents for targeting overseas Hongkongers in their surveillance activities. One of the people arrested actually committed suicide afterwards.

Nathan Law was one of the targeted activists in that particular case. He also has a Hong Kong bounty and warrant targeting him. This surveillance has caused quite a scandal because they’ve traced money to cover expenses to the Hong Kong government and the involvement of officials in the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office in London. There’s now a movement by people concerned about it to actually shut down such economic and trade offices in London and elsewhere.

Supporting Hong Kong Activists Abroad

Alvin Cheung: In the penultimate chapter, you talk about some of the steps taken internationally in support of Hong Kong, including in the US, the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act and the Hong Kong Autonomy Act, and scrutiny before the UN Human Rights Committee. What more do you think ought to be done?

Michael Davis: I think there’s a number of things that can be done. There are two fronts. One is to consider ways to pressure and educate the Hong Kong and Beijing governments on the consequences of such behavior and maybe encourage change? On that front, the tools are rather weak. There is not a lot you can do because when you try to mobilize official pressure by testifying in parliamentary bodies, issuing reports, and encouraging official statements, the Beijing government just pushes back and a lot of it goes nowhere. One strategy that may be useful, is to cause some economic consequences for companies that participate in transnational repression in one form or another.

We know that goods produced by incarcerated Uyghur people, for example, are blocked in some countries from import. Other things that could be done on that economic front would be to pass laws that sanction companies with criminal prosecution or otherwise if they engage in human rights violations. The United States, for example, has a law that prohibits corruption abroad. Companies that engage in corruption overseas can be prosecuted or sued. It seems to me if one of the fundamental commitments of both the United States and the United Kingdom is the protection of international human rights, then why not have laws that regulate human rights practices by companies operating abroad.

A human rights violation anywhere is a violation everywhere.

What we’re doing now to address such concerns is using targeted sanctions, but targeted sanctions have had a limited effect. If companies are operating not just under a law that targets China, but a general law regarding human rights violations abroad, they may think twice before investing in countries with questionable human rights practices. If they were subject either to lawsuits for violations or to prosecution, then countries trying to attract investments and participation by international companies would suffer consequences for their human rights violations.

The Hong Kong government is working overtime trying to attract international meetings and promote business in Hong Kong. Maybe such laws would persuade governments in Hong Kong and Beijing to change course in certain ways. It’s important to remember that every member of the UN is obligated to work towards human rights protection everywhere. A human rights violation anywhere is a violation everywhere. For members of the multilateral human rights treaties, that responsibility increases. So that’s one side.

The other side for policy attention is how you deal with Hongkongers who have fled Hong Kong and are living abroad. They may encounter very serious problems if their economic needs are not met. They may especially struggle to meet professional requirements. They may even have to go back to school and start over. For Hongkongers in the UK and Ireland, this has been a problem, as it no doubt is elsewhere. It’s difficult when you’re in exile to be an effective advocate for local political change, especially in an age when immigration itself is under attack.

Policies that are more conducive to the needs of exiles and refugees are important as a general matter. In the case of Hong Kong, of course, the UK has a special responsibility. It’s unacceptable that some people in professions like social work, law, or medicine can’t get properly qualified to practice their profession, given that they grew up and were trained under a system that was regulated by the UK. These kinds of things can be done to help deal with the exile community, to protect them from international repression, and enable and assist their advocacy for change in their country of origin.

Is Hope Lost? Grounds for Optimism

Alvin Cheung: Final question from me. You entitled the last section of your book “Is Hope Lost?” Are there any grounds for optimism regarding conditions in Hong Kong or in the Hong Kong diaspora?

There are no signs at present that the Chinese Communist Party is changing its methods towards a more open and progressive society.

Michael Davis: Sadly, there are not a lot of avenues to promote change on the Hong Kong front at the moment. We are dealing with what we’re told is the second most wealthy country on earth, maybe the second most powerful country as well. There are no signs at present that the Chinese Communist Party is changing its methods towards a more open and progressive society. In fact, under the current leadership, it seems to be going in the opposite direction. There might be slight hope along the lines we just discussed.

If Hong Kong’s economic agenda falters there could be some moderation. But my guess is that Beijing won’t let Hong Kong’s economy falter in any significant way. It can just replace international engagement with mainland engagement in Hong Kong. It is a difficult situation. People in exile can’t afford to give up hope.

We can see that for many Hong Kong exiles conditions are very difficult but we can advocate change to make policies that assist them. A person with a university degree or a practicing social worker shouldn’t have to drive a truck for a living when they gain exile in the UK. They should be able to qualify in their profession. These are areas where a lot can be done. And hopefully in democracies, people will listen.

Alvin Cheung: Well, Professor Davis, not a very uplifting note, but that’s the note we’re ending on. Thank you very much for your time.

Michael Davis: Thank you.

Alvin Y.H. Cheung is an Assistant Professor at Queen’s University Faculty of Law and a Non-Resident Affiliated Scholar at NYU’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute. His research focuses on the systematic abuse of sub-constitutional legal norms and institutions by authoritarian regimes. He holds a J.S.D. (2020) and an LL.M. in International Legal Studies (2014) from NYU, as well as an M.A. (2011) from Cambridge. He has also served as a barrister in Hong Kong and lectured in Law & Public Affairs at Hong Kong Baptist University. For more information, visit his website.