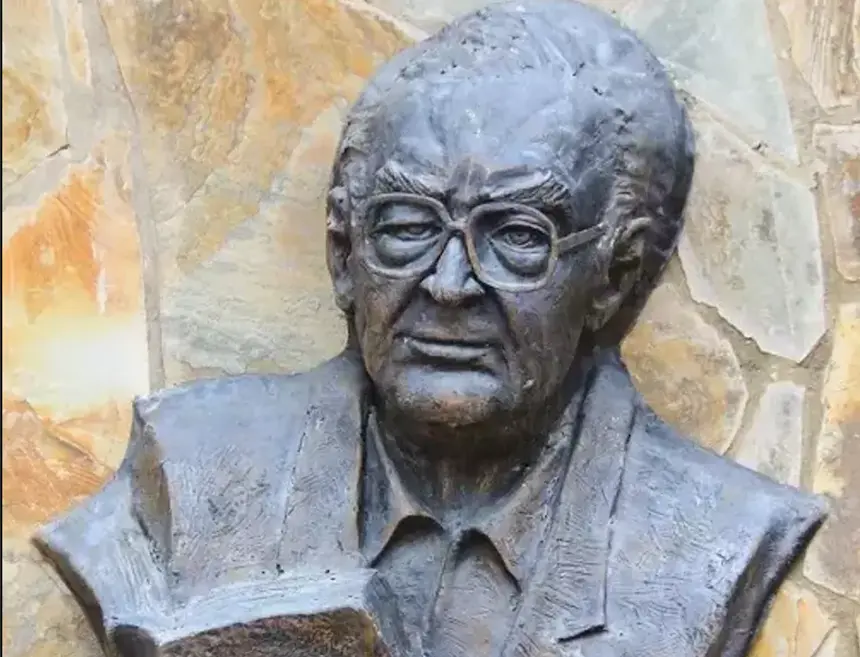

When I was a child, I would often sit cross-legged on the floor of my grandmother’s study room, thumbing through her collection of dusty books. Among them was a tattered copy of İnce Memed by Yaşar Kemal, a Turkish author whose words leaped off the page and conjured entire worlds. I was 9 years old and unable to grasp the full importance of his storytelling.

Yet I was captivated by how his prose made me angry about the struggles of peasants against oppressive landlords. His book didn’t tell but showed me the landscapes of injustice and resistance in a formidable way. His writing was more than a narrative for me. It was a bridge to understanding humanity’s capacity for both suffering and hope. It was then that I realized how powerful, clear, and evocative writing can connect distant worlds and bring complex ideas to life.

Clear writing is not a compromise on intellectual rigour but a pathway to deeper understanding and cross-disciplinary engagement.

Even as a child, I felt the power of his words to transport, educate, and inspire. It wasn’t just that he told a story well. It was that he made me care deeply about people and places I had never known. His prose showed me that writing could transcend the page. It could connect the reader to something larger than themselves.

Bridging Academia and Literature: Insights Beyond the Ivory Tower

Writing clearly creates a pathway for academics to step out of the ivory tower and engage meaningfully in the public square where ideas can inspire change and foster understanding.

The ability to communicate arguments effectively is an ethical obligation for academics.

Decades later, I am working at a British university as an academic teaching and researching injustice, violence, conflict, and crime. My work frequently involves uncovering the hidden structures that enable exploitation and inequality.

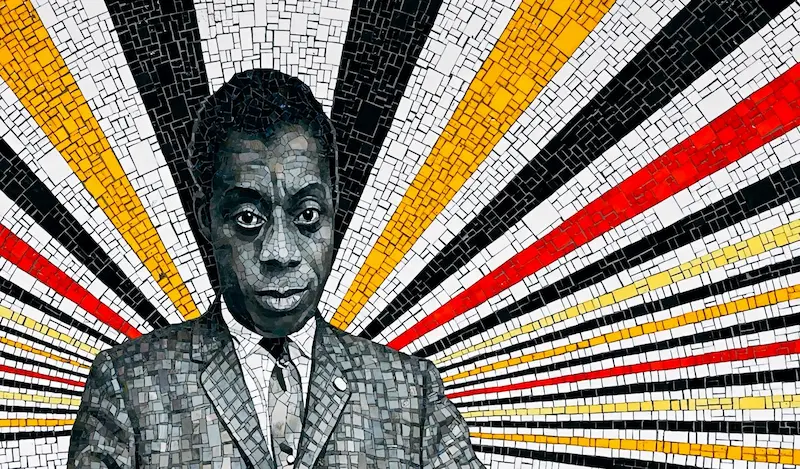

I explore complex systems that resist easy explanation. Yet, even in my academic journey, I have continued to look to literature for clarity and insight. While conducting years of field research on the mafia in Palermo, I found myself learning as much from a Sicilian author’s fictitious books as I did from academic texts.

Leonardo Sciascia’s Il giorno della civetta (The Day of the Owl) was a revelation for me. It was an eye-opening exploration of the complexity of the mafia in daily life. His sharp prose and narrative craft illuminated the entangled relationships between power, fear, and silence in a way that no scholarly work ever could.

Literature as a Lens to Understand Complex Realities

Similarly, Andrea Camilleri’s La forma dell’acqua (The Shape of Water), the first of the Inspector Montalbano series, masterfully blended mystery and social commentary. It revealed the complex interplay of corruption, politics, and crime in Sicily.

Camilleri’s ability to weave wit, humanity, and a sagacious critique of societal norms into his narratives deepened my understanding of the cultural and historical forces that have sustained the mafia’s grip. Both authors demonstrated how literature can articulate the unspeakable. In doing so, we can attain clarity and perspective where conventional analysis often falters.

Kemal, Sciascia, and Camilleri demonstrated that the art of writing creates wide windows into complex realities. Through such prose, readers—academic or not—can grasp the gravity of injustice and the resilience of those who fight against it.

The Art of Prose

Academic writing often prioritizes technical rigor at the expense of readability. Yet this creates a dangerous divide; a divide that alienates even well-educated readers. Precise terminology and methodological specificity are, certainly, essential for scholarly discourse.

However, overly dense and jargon-laden language obscures arguments. Achieving clarity demands time and work. But all starts with a deliberate effort to translate complex ideas into accessible writing without diluting their substance.

Carlo Rovelli’s book, Seven Brief Lessons on Physics, is evidence of an engaging writing style. In the pages of the book, we understand that clear writing can make theoretical physics appealing to many of us, even if it is full of abstract concepts.

Writing clearly is about democratising knowledge

Similarly, the microhistorian Carlo Ginzburg demonstrates the transformative power of narrative by using a single person’s life to illuminate the complex relationship between social and cultural forces.

These examples remind us that clear writing is not a compromise on intellectual rigour but a pathway to deeper understanding and cross-disciplinary engagement.

Prose clarity also signals respect for the reader’s time and effort. When academic writers value communication as much as the ideas they present, they invite the public to participate in critical and pressing conversations. Prioritising clarity, scholars amplify the impact of their work and fulfil their responsibility to share knowledge broadly. In doing so, they can bridge the often-criticised divide between academia and society.

Ethical Responsibility

The ability to communicate arguments effectively is an ethical obligation for academics. The academic work exists to advance knowledge and inspire meaningful change. Yet, when arguments are shrouded in impenetrable jargon, they remain within the confines of disciplinary silos. It becomes a missed opportunity.

Since the brilliant inventions of the Renaissance, science has been shaping our journey for a prosperous world. Yet this power depends on the level of impact. In navigating the complexities of modern life, policymakers, educators, and the wider public consult scholarship for guidance. If these groups are unable to engage with the ideas due to overly exclusive writing, we risk destroying what we have built onerously. Then, the question begs for an answer from us academics is: who benefits from research that remains unread or misunderstood?

Scholars have access to resources, platforms, and expertise that many don’t. Yet that privilege also implies an obligation to share knowledge with broader audiences. This is the reason that the responsibility to communicate clearly stems from this same privilege. When arguments are liberated from the boundaries of dense academic writing and resonate with policymakers, educators, activists, and ordinary citizens, they enhance the relevance of scholarship and make a difference in our rapidly transforming world.

Writing clearly is about democratising knowledge. It allows academics to leave their ivory tower and become public intellectuals. Their writings function as the engines of societal progress. Perhaps the urgent question needs to be raised for the unconvinced academics: what is good in an argument if it fails to reach the ears and hearts of those who need it most?

Expanding the Impact of Scholarly Work

Engaging prose has the unique ability to carry ideas. It opens doors to broader audiences through books, essays, and public forums. When academics prioritise accessibility, they breathe life into their research. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring is a good example of this power. Her evocative prose exposed the devastating effects of pesticides on the environment, catalysing the modern environmental movement and inspiring sweeping legislative reforms.

Some ideas demand years of nurturing, the way a garden needs seasons to bloom.

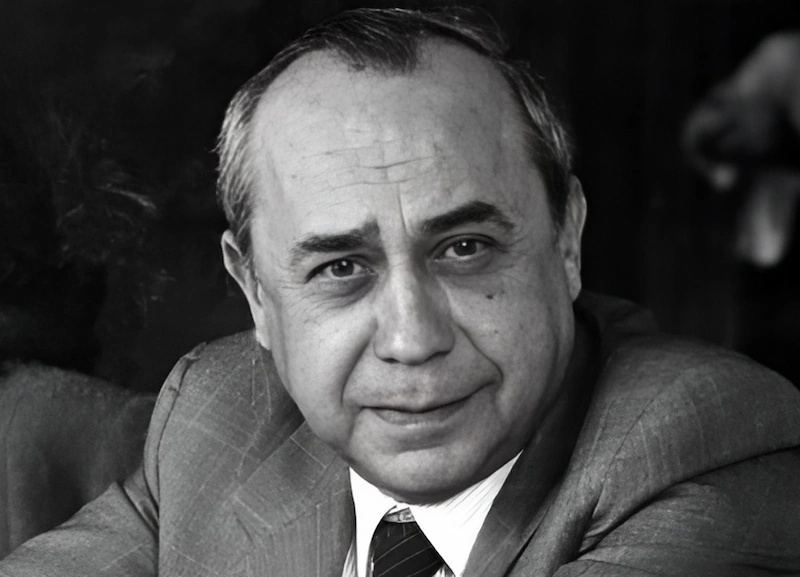

Sociologist Erving Goffman’s The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life shows how sociological insights make huge difference by distilling complex ideas about social interactions and identity. Goffman explained the multi-layers between the individual and society through relatable concepts to everyone eloquently. Yet his books have captivated both academics and lay readers. Thanks to this plain but elegant writing, we can grasp the role of human behaviour in everyday life. These works demonstrate that well-crafted academic arguments, delivered in accessible language, can influence policy and spark global conversations.

When academics write with their readers in mind, their works become lighter, a tool helping people in the dark to find their ways. This is such a huge empowerment. Those books reaching a wider audience create avenues for ideas and possibilities. A sociologist who writes clearly about systemic inequality may inspire educators to rethink how to organise the content and classroom structures. A policymaker may implement inclusive policies. A historian who crafts a narrative accessible to the public may help society better understand the present through the lens of the past.

Clear and engaging writing helps to dismantle the argument that academic research suits better for an elite audience. Conversely, when academics care about their readers, they create pathways to inspire and empower. We can easily check the impact of scholarly work not in its complexity but in its ability to lead a change—a change that begins with how it is written.

The Constraints of Managerialism on Scholarly Writing

The challenge lies not in academics’ willingness to write in clear prose, but in the constraints imposed by the relentless demands of quantified managerialism in academia, which often leaves little room for the time and effort such writing requires. One of my line managers at a British university once raised a question that felt less like a conversation and more like a calculation: “Isn’t the number of outputs for your next-year objectives too few?”

His question was cold and clinical. Could we reduce the craft of writing to an assembly line? There was no recognition of the emotional weight some subjects demand. In the eyes of those managers, we are not thinkers or creators but machines that are expected to churn out polished papers on a rigid schedule, indifferent to the complexities of thought or the depths of emotion.

This mechanisation of academic life drains its soul. Some works need to simmer over time, not just to do justice to their subject but also to care for their readers. How can we write about grief, injustice, or humanity’s failings with integrity if we are asked to keep one eye on a stopwatch? Some ideas demand years of nurturing, the way a garden needs seasons to bloom.

Other subjects come with emotional tolls that require pauses, reflection, and even silence before they can find their way into words. When we disentangle academia from its neoliberal scaffolding—this quantified, profit-driven managerialism that sees human beings as little more than numbers on a spreadsheet—then perhaps we will rediscover what matters in writing.