Japan’s Arctic Power: From Imperial Reach to Strategic Re-emergence

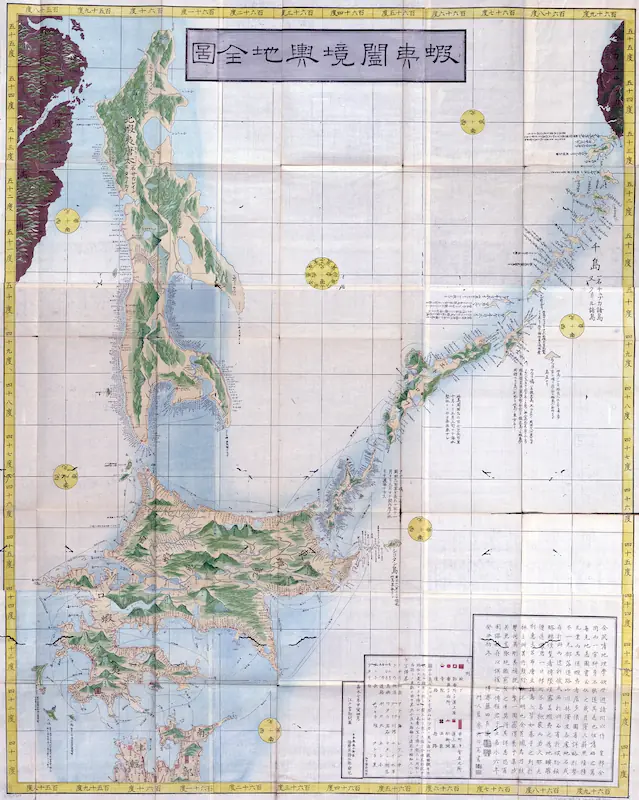

Japan was, for much of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a North Pacific great power in command of Northeast Asia’s near-Arctic seas and insular territories, and was even, albeit briefly, a global Arctic power with its possession of the outer Aleutian Islands.

- Japan’s Arctic Power: From Imperial Reach to Strategic Re-emergence

- Japan’s Strategic Arcticness and Northern Power Trajectory

- Contemporary Echoes of an Earlier Age of Northward State Expansion and Collision

- The Aleutians and the End of Japan’s Northern War Effort

- Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

- From the Aleutians to the Kurils: Arctic Lessons and Risks

- The Kuril Dispute in the Context of the Ukraine War

- Hokkaido, Strategic Exposure, and Emerging Arctic Chokepoints

Invaded and held for a year during World War II, Tokyo’s occupation of the outer Aleutian Islands put Japan in a position to block the projection of American air and sea power from North America across the High North Pacific, thus preventing a direct assault on Japan’s main islands from the north. While the outer Aleutians were the first islands to be liberated when America regained its war footing, Japan’s ability to even briefly hold them placed it among the world’s Arctic powers during an illuminating, and highly contested, moment in world history.

The collapse of Japan’s northern foothold in Alaska and its subsequent collapse in Sakhalin and the Kurils marked the end of the Pacific War.

In the post-WWII years, Japan’s formerly held Kuril Islands have remained, with controversy and continued protest by Tokyo, under Russian occupation within sight of Hokkaido’s shores, and as Russia resurges as a military power, its Kuril possessions have undergone re-fortification and modernization. As Russia increasingly aligns with China in a mutual diplomatic, geostrategic, and economic embrace, Japan is poised to re-emerge as a front-line state in the West’s diplomatic and military response. This is due to its favorably situated forward geography for the projection of air and sea power into the North Pacific and beyond to the Pacific Arctic region, with its proximate access to the eastern terminus of the Northern Sea Route.

Japan’s Strategic Arcticness and Northern Power Trajectory

With the narrow Soya Strait increasingly transited by Russian and Chinese war ships, Tokyo’s century-and-a-half possession of Hokkaido and its subsequent northward expansion to Sakhalin, the Kurils, and (briefly) the Aleutians, alongside its active contemporary polar research community and its numerous elements of an inherent Arcticness (including its indigenous engagement with the Ainu, enduring whaling tradition, and innovative adaptation to cold climates), positions this North Pacific archipelagic nation to, once again, become an important regional military power and a key western ally in an increasingly active and more muscularly contested Arctic region.

Indeed, the unresolved border dispute between Japan and Russia over the southern Kurils that’s been simmering since the end of World War II presents a contemporary fault line that could potentially erupt into war should the region destabilize under new pressures of China’s expanding Arctic ambitions.

Japan has itself experienced its own long, dynamic sovereign journey as a northern, and briefly Arctic, power, and at the height of its empire in World War II was the predominant military power in the High North Pacific and Bering Sea; during its year-long possession of the outer Aleutian Islands, Japan was a bona fide polar power – capping a century of expanding into territories hitherto held by Russia (and, before 1991, the Soviet Union) in what is widely described as “the Russian Far East,” but which increasingly became Japanese-held territory from the middle of the 19th century through to nearly the middle of the 20th.

Japan’s experiences during this stretch of historic northward territorial and maritime expansion inform, to a considerable extent, its understanding of the current great power competition (GPC) dynamics in the region. Also relevant in this context is Japan’s identity, and experiences, as a whaling nation whose enduring whale harvesting economy and culture provides it with further touch points for mutual understanding with Arctic nations and peoples.

Additionally, Japan’s northernmost major island, Hokkaido, is the traditional homeland of the Ainu indigenous people, who have in recent years made noted gains in restoring their indigenous rights, mirroring those of their counterparts in the Arctic states. This development alone provides Japan with an additional layer of understanding and engagement with the indigenous peoples of the Arctic as well as the Arctic states on a wide spectrum of issues ranging from minority rights to sustainable economic development, (re)distribution of wealth, and national sovereignty.

These perspectives help to inform and contextualize Japan’s past, present, and future as a northern state with growing Arctic interests, and, in many ways, an inherent Arcticness that positions it well for the coming years of an increasingly contested Arctic.

Contemporary Echoes of an Earlier Age of Northward State Expansion and Collision

World War II in the Pacific ended just over 80 years ago with Japan’s historic August 15, 1945 acceptance of surrender, bringing to a close Japan’s stunning rise to and fall from its globe-spanning heights of great power expansion in the prior decades after its navy defeated Russia in 1905, paving the way for its expansion first to Manchuria and Korea, and then as far north as Sakhalin island and the Kuril island chain before turning its military attention to the subjugation of Southeast Asia and Oceania.

Japan’s defeat, amongst other things, brought an end to Tokyo’s bid to become a polar power which took form with its invasion and occupation of the outer Aleutian Islands, which denied the United States marine access across the international date line in the North Pacific and Bering Sea. With Japan’s eventual expulsion from the Aleutians, the four southern-most Kuril Islands (Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan, and the Habomai) were soon invaded and occupied by Soviet Russia, which also seized Japan’s territorial possessions on southern Sakhalin Island by force, which had come under Japanese control first from 1855–75 and again after its victory in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War.

The Aleutians and the End of Japan’s Northern War Effort

Japan’s remote Alaska garrisons in the outer Aleutian Islands had been fully reconquered two years before its World War II surrender by a joint U.S.–Canadian liberation force assembled methodically in the Pacific waters off North America’s west coast; the first of a long and bloody island-hopping campaign that severed Japan’s tenuously overstretched naval sea lines of communications (SLOCs).

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

The collapse of Japan’s northern foothold in Alaska and its subsequent collapse in Sakhalin and the Kurils marked the end of the Pacific War, thereby reversing Japan’s imperial expansion in the preceding years. The U.S.–Canadian campaign to liberate the outer Aleutians was described aptly by Ira F. Wintermute in 1943 as a “war in the fog,” as much for the impact of the North’s infamous weather as for the campaign’s many frictional consequence of the fog of war.

From the restoration of U.S. sovereignty over the island of Kiska in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands chain on August 15, 1943, to the Emperor’s dramatic surrender announcement two years later to the very day in Tokyo Bay, a determined, bloody and successful island-hopping campaign would transpire from the frigid subarctic waters of the Aleutians to the tropical waters of the South Pacific.

From the Aleutians to the Kurils: Arctic Lessons and Risks

The historic importance of the war in the Aleutians cannot be overstated and its geopolitical linkage to the broader Pacific War offers insights for the contemporary world and the reemergence of GPC in the Arctic and the unfolding remilitarisation of the region, where the prospect of a conflict is now considered possible, if not yet probable.

Russia has since used infrastructure from the Kuril Islands in the war against Ukraine, transferring some anti-aircraft missile defense systems from the islands to Ukraine.

With growing global geostrategic interest in the Arctic and subarctic regions, the lessons of the Alaskan and High North Pacific battles of WWII are particularly salient once more, and can be used to contextualize and re-frame Japan’s historic role as a geopolitical contender that successfully disrupted and diminished the capacity of both the United States and Soviet Russia to project power into the Arctic and North Pacific.

This is a role China could now seek to emulate. However, a militarily resurgent and aggressively nationalistic Japan could – albeit not imminently likely – also potentially reprise this historic role should this Northeast Asian and North Pacific gateway to the Arctic via the Northern Sea Route (NSR) ever enter into a period of intensifying geopolitical instability.

This is particularly the case with regard to the status of the Kuril Islands and the prospect of renewed conflict between Japan and Russia over them and the importance of Hokkaido as a staging ground. Samara Choudhury discounts the likelihood of a renewal of armed confrontation between Tokyo and Moscow over the disputed southern Kuril Islands’ sovereignty, given Russia’s status as a nuclear power and Putin’s recent re-militarization of the islands. However, Choudhury cautions that it remains “unlikely that the conflict will be resolved in the near future. The ambiguity surrounding control over the islands only allows for tensions to rise.”

The Kuril Dispute in the Context of the Ukraine War

Quite interestingly, the Kuril Island dispute has its own curious and potentially significant interconnections with the Ukraine War, as Choudhury points out:

“On October 7, 2022, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky signed a decree formally recognizing the Kuril Islands as a Japanese territory temporarily occupied by Russia, likely as a sign of solidarity with another Russian-occupied country. Russia has since used infrastructure from the Kuril Islands in the war against Ukraine, transferring some anti-aircraft missile defense systems from the islands to Ukraine. Additionally, approximately 60 percent of the population of the Kuril Islands is descended from Ukrainians forcibly moved to the archipelago by the USSR after it seized the islands in 1945.”

Hokkaido, Strategic Exposure, and Emerging Arctic Chokepoints

While Japan remains a loyal Pacific ally of the United States and a vast and vital offshore platform for the projection of military power throughout Northeast Asia, Washington has remained largely disengaged from Japan’s Kuril Island dispute with Russia. Moreover, Hokkaido remains far less integrated with American military power compared to Okinawa in Japan’s south. However, as the Arctic becomes increasingly re-militarized, Hokkaido is where Japan continues to face off against Russia over these disputed islands – and where the restoration of Japanese sovereignty over the four southernmost Kurils remains a simmering sovereignty dispute that could, in time, become a future flashpoint of conflict.

As Alec Rice describes, Hokkaido is “bordered by the Sea of Japan to the west, the Sea of Okhotsk to the northeast, and the Pacific Ocean to the southeast. Toward its south it is separated from the Japanese island of Honshu by the Tsugaru Strait, while the Russian island of Sakhalin is only forty-three kilometers away across the Soya Strait to the north. Both the Soya and Tsugaru Straits are vital for Russian and Chinese military and commercial shipping access through the Sea of Japan to the Pacific.”

In the event tensions rise, waters adjacent to Hokkaido – and in particular the 26-mile Soya (also known as La Pérouse) Strait between Hokkaido and Sakhalin – could emerge as a vulnerable chokepoint that could jeopardize NSR shipping between Northeast Asia and Europe. Indeed, in the event Hokkaido becomes contested militarily, the entire region could become embroiled in a naval clash of a scale unseen since World War II, and as consequential as the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, which planted the seed for Japan’s imperial expansion and the global war that followed.