Selective Justice

In March 2025, President Donald Trump marched into the Justice Department and declared an end to the “Department of Injustice.” He vowed to restore “law and order” by cracking down on urban crime and illegal immigration, rallying support for his punitive agenda. But while Trump railed against street crime, Attorney General Pam Bondi quietly rolled back the government’s role in prosecuting corporate crime. Trump’s tough-on-crime rhetoric has been paired with the most aggressive effort in over a decade to dismantle financial regulation – slashing capital requirements, weakening consumer protections, and scaling back corporate bribery enforcement.

In that March speech, Trump pledged to restore “safety in our cities as well as our communities” by punishing crime, but only certain kinds of crime seemed to count. This bifurcated strategy of punishment in the streets and leniency in the suites echoes an older American tradition of intensifying carceral violence while eroding elite accountability, which is a defining feature of the American state. Understanding this dualism, and how it became embedded in law, requires reckoning with the institutional architecture and historical choices that built and sustain it.

Punishment does not resolve the economic inequalities that drive street crime, and regulation rarely disrupts the profit incentives behind corporate abuse.

That’s the project of my book, Dual Justice: America’s Divergent Approaches to Street and Corporate Crime, which traces the ideological and institutional roots of these inequalities and charts a different path forward. The book shows how America has built two distinct legal systems – a criminal justice system designed to harshly punish street crimes, and a regulatory state designed to administratively monitor corporate harm.

These systems define illegality differently depending on who commits it and where. Street-level shootings and robberies are treated as individual moral failings warranting punishment, but profit-driven corporate decisions with deadly consequences are framed as unfortunate but inescapable economic realities to be regulated. But both forms of harm stem from the same broken economic system, and until we confront that reality and the inequalities in how they are governed, the cycles of harm they cause will only persist.

The Ideological Roots of Legal Inequality

This divergence reflects long-standing ideological assumptions dating back to the Progressive Era, a pivotal moment in American political development when two significant parts of the legal system emerged.

First, the modern criminal justice system began to form, which focused on managing offenders through individualized measures geared towards rehabilitation or punishment.

At the same time, the federal regulatory state began taking shape. Administrative agencies and commissions were established to manage the robber barons’ excesses, with lawmakers casting their actions as misguided but natural extensions of their entrepreneurial spirit requiring corrective regulation.

These institutional developments were shaped by two ideological frameworks: rehabilitative ideology and regulatory ideology. Both had roots in eugenic understandings of human behavior but operated in different ways.

Rehabilitative ideology viewed poor and non-white street criminals as genetically inferior and deserving harsh penalties, whereas regulatory ideology saw corporate offenders as rational actors whose missteps were byproducts of entrepreneurial ambition that should be managed, not condemned.

Regulation for Elites, Punishment for the Poor

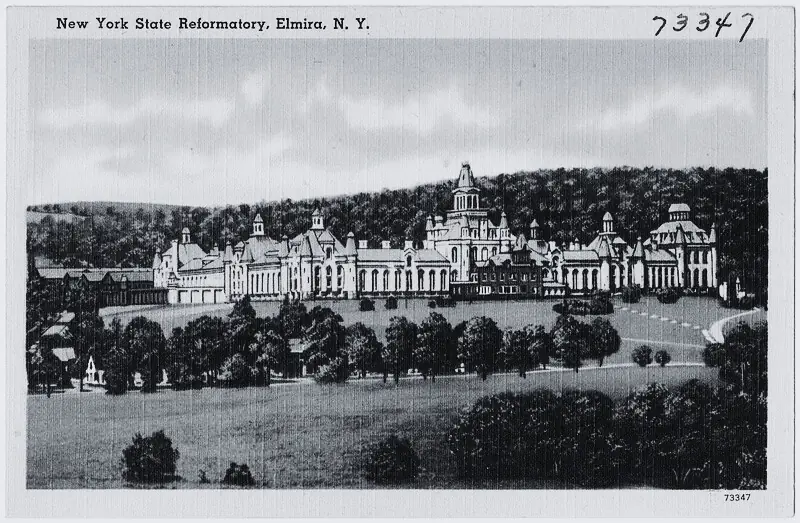

Rehabilitative ideology masked its punitiveness in the language of reform. Early proponents of rehabilitation, like Zebulon Brockway, the Warden of New York’s Elmira Reformatory, exemplified this duality. While claiming to rehabilitate offenders, Brockway and other progressives embraced the eugenic theories of criminologist Cesare Lombroso, who suggested that some people were genetically inferior “born criminals” so biologically predisposed to crime that they were irredeemable.

Brockway described such people as “defective fellow beings,” and he and other American reformers advocated punitive interventions ranging from lengthy incarceration to compulsory sterilization for such “incorrigibles.” This rendered the rehabilitative approach a dual-edged technique that offered conditional reform to the curable while condemning those deemed eugenically irredeemable to harsh justice.

American law continues to reflect the eugenic underpinnings of rehabilitative and regulatory ideology.

Alternatively, the regulatory ideology that shaped Progressive Era governance treated corporate harm not as crime, but as the rational outgrowth of economic structures that could be managed through administrative penalties.

Institutions like the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) were designed to manage the abuses of industrial capitalists through regulation, even as populists and corporate critics pushed for criminal accountability.

This choice reflected a broader double standard rooted in eugenic thought, as scholars pathologized street criminals as genetically inferior while excusing the misconduct of business elites. For instance, in his 1904 book The Diseases of Society, physician G. Frank Lydston claimed that violent and property offenders exhibited cranial deformities common among the poor, marking them as biologically predisposed to crime.

By contrast, Lydston described elite wrongdoers as “respected citizens” with “great inherent capacity for good,” and insisted that they lacked the degeneracy warranting punishment for those like the “petty thief.” Since these men exhibited no inherent deviance, they required neither rehabilitation nor punishment.

Lydston’s logic was echoed by influential figures like Louis Brandeis. During debates over the FTC, Brandeis told Congress that corporate misconduct lacked the “moral taint” of ordinary crime. Industrial wrongs, he argued, should be addressed not through threat of punishment but by regulating economic conditions to render business malfeasance “unnatural.” Yet as a Supreme Court justice, Brandeis would join the majority in Buck v. Bell (1927) in an opinion upholding compulsory sterilization as preferable to, among other things, “waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime.” Such contradictory logics naturalized elite impunity while justifying punitive governance for the lower classes, cementing a legal order distinguishing between harm that must be punished from harm that can be managed.

Modern Biases, Old Logics

American law continues to reflect the eugenic underpinnings of rehabilitative and regulatory ideology. Contemporary risk assessments, for instance, rely on factors like prior arrests, employment history, and financial stability – metrics skewed by racial and economic inequality – to classify individuals as reformable or high-risk, reproducing old distinctions between the corrigible and incorrigible while mapping them onto modern racial and class dynamics.

Meanwhile, corporate misconduct remains governed through civil, administrative, and equity law, reinforcing the idea that elite lawbreaking is less criminal than street crime. Consider Donald Trump’s 2020 pardon of Michael Milken, who was convicted for financial crimes during the 1980s savings-and-loan crisis.

In defending the pardon, Trump lauded Milken’s business acumen and said that prosecutors unfairly prosecuted Milken’s “innovative financing mechanisms” which had only been governed as “technical offenses and regulatory violations” in the past. Such a framing exemplifies how elite wrongdoing is often cast as a misguided relative of the entrepreneurial spirit, mistaken for crime only upon regulatory overreach.

Dual Justice charts a path toward a system grounded in fairness, dignity, and democratic accountability.

Both rehabilitative and regulatory frameworks conceptualize harm through inherited assumptions about racial and class hierarchy. The poor are cast as inherently criminal and punished accordingly, while corporate actors are seen as naturally gifted and rational, their misconduct requiring only technocratic correction. As such, neither framework confronts the structural causes of harm.

Punishment does not resolve the economic inequalities that drive street crime, and regulation rarely disrupts the profit incentives behind corporate abuse. And by upholding this double standard, American law divorces elite economic harm from the moral condemnation imposed on poor offenders, maintaining a system that shields the powerful, criminalizes the vulnerable, and breeds cynicism, resentment, and demands for structural change.

Reforming Regulation and Confronting Limits

Dual Justice contends that meaningful change requires a dual strategy: institutional reforms to the criminal justice system and regulatory state, and deeper, structural transformations of the political economy that rehabilitative and regulatory ideologies sustain. While pragmatic institutional reforms can yield incremental improvements and alleviate urgent problems, they remain insufficient in providing fundamental change, which can only be achieved through addressing the underlying economic conditions that produce inequality and wrongdoing.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

Though the book also discusses criminal justice reform, this article emphasizes its proposals for repairing the regulatory system and reshaping corporate governance. Importantly, Dual Justice warns against addressing corporate crime through a punitiveness mirroring the harshness of street crime enforcement. Doing so would simply expand the carceral state. Instead, the book endorses a balanced approach to corporate regulation, drawing on Braithwaite and Ayres’s “responsive regulation” model. This framework envisions a “sanctions pyramid,” escalating enforcement in proportion to the severity and frequency of misconduct. Empirical studies suggest that a strategic mix of administrative sanctions and targeted prosecutions effectively deters corporate crime without relying on excessive incarceration.

Such a shift would require significant reinvestment in regulatory agencies. However, current budget models estimating the cost of agency operations often obscure the financial benefits of enforcement by failing to account for revenue generated by agencies through fines and settlements. Consequently, agencies like the SEC and DOJ’s Antitrust Division regularly recoup far more than their operating costs, yet their work is portrayed as inefficient. For instance, President Trump’s push to slash the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau rests on a misleading account of its costs, ignoring the vast sums it has returned to defrauded consumers. Recognizing the fiscal returns of robust enforcement could bolster political support for expanding agency capacity.

The book also seconds Jennifer Taub’s proposal for a dedicated DOJ division to prosecute complex financial crimes.

Reflecting on the failed Financial Institutions Fraud Unit formed after the S&L crisis, Dual Justice emphasizes that any new unit must be empowered with independent investigative authority and strong coordination capabilities with regulators. It should also have the capacity to track repeat offenders independently and could be funded by reallocating revenues from enforcement agencies that generate income.

Another proposal addresses the data deficit in corporate crime enforcement. Because many illegal business practices are handled administratively, few comprehensive statistics exist on corporate offenders.

Dual Justice calls for a centralized database cataloging regulatory actions and criminal referrals across agencies. Such a clearinghouse would allow regulators to identify firms with repeated infractions, even when dispersed across agency jurisdictions, and respond accordingly.

Still, the book acknowledges the limits of such institutional change. Regulatory fixes can legitimate a political economy that privileges corporate power and profit over public welfare. Even aggressive corporate prosecutions remain reactive tools unable to uproot the structural incentives that drive corporate crime. For these reasons, the book advances more radical political-economic transformations to the corporate economy.

Beyond Reform: Radical Remedies for Economic Justice

One proposal calls for breaking up financial institutions to eliminate “too-big-to-fail” incentives and limit systemic risk. Capping institutional size, such as by restricting bank exposure to 3% of GDP or reinstating the Glass-Steagall firewall between commercial and investment banking, would compel firms to downsize and reduce the likelihood of taxpayer-funded bailouts. By removing the implicit guarantee of government rescue in the event of failure, such measures would diminish incentives for large corporations to engage in reckless risk-taking. Though politically challenging, such reforms have attracted bipartisan interest as mechanisms for restoring market discipline and democratic accountability.

Instead of replicating the justice system’s punitivism in corporate suites, Dual Justice argues the reverse: we should apply the regulatory principles used to prevent crime in corporate boardrooms to economically marginalized communities.

A second proposal supports a corporate chartering regime modeled on the Accountable Capitalism Act. This would require corporations with over $1 billion in annual revenue to obtain a federal charter mandating obligations to workers, consumers, and communities, not just shareholders. The proposal also empowers state attorneys general to sue to revoke charters for illegal conduct and ensures worker representation on corporate boards, thereby promoting social responsibility, checking exploitative behavior, and curbing the profit-maximization incentives that encourage disregard for social welfare.

The third, and most ambitious, proposal advocates for partial nationalization of the financial sector. This has historical and international precedents – hundreds of state-owned banks exist around the world, the U.S. had ownership stakes in the First and Second Banks of the U.S., and the state of North Dakota has operated a successful publicly-owned bank for over a century. Public banks could offer stable, risk-averse alternatives to private institutions, creating competitive pressures for financial institutions to behave responsibly. Public banks could also provide services to underserved communities, invest in public interest ventures, and promote public goods, checking the economic conditions that fuel street crime.

Reversing the Logic of Punishment

Instead of replicating the justice system’s punitivism in corporate suites, Dual Justice argues the reverse: we should apply the regulatory principles used to prevent crime in corporate boardrooms to economically marginalized communities. This emphasizes improving the economic conditions of disadvantaged communities as a strategy to govern street crime.

Federal investments in public housing and public schools could provide crime-reducing economic stability, while public jobs programs could help give people in criminogenic communities meaningful, dignified work. Rather than focusing on fixing individuals, such a regulatory approach on the streets would reduce the precarity that often underpins criminal behavior. Centering economic justice over punitive measures could help us to move beyond the flawed rehabilitative model that perpetuates myths about individual incorrigibility.

What emerges is a vision for justice grounded not in carceral expansion or regulatory tinkering, but in a wholesale reorientation of the political economy. The status quo of excusing corporate harm while punishing the most marginalized among us has produced profound alienation and cynicism, but by calling for structural political economic transformations to the root inequalities that shape both corporate and street crime, Dual Justice charts a path toward a system grounded in fairness, dignity, and democratic accountability.