In The Return of the Native: Can Liberalism Safeguard Us Against Nativism?, Jan Willem Duyvendak and Josip Kesic provide a rigorous and insightful critique of a crucial contemporary political phenomenon: the spread of nativist logic across various ideological contexts internationally.

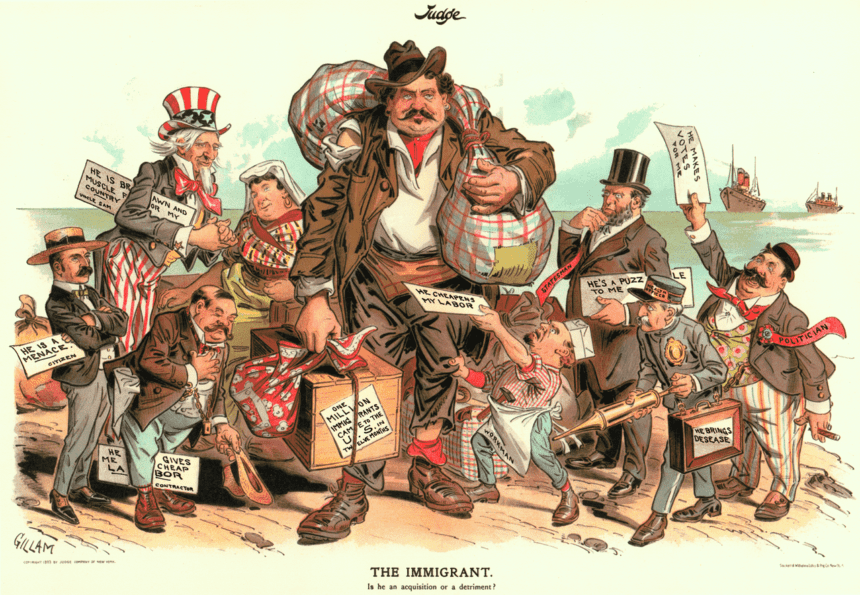

The authors identify three key elements characterizing the logic of nativism: the designation of certain groups and practices as “native” and others as “alien,” the perception of foreignness as a threat, and the advocacy of exclusion as the preferred means to confront this threat. The criteria for distinguishing “natives” from “aliens” are manifold, touching on aspects such as religion, race, ethnic origins, and even political orientation.

Nativist sentiment has now expanded to encompass the national culture of secularity, where values such as freedom of thought, expression, and sexuality are increasingly instrumentalized.

The book examines the assumptions underlying the discourse on “the failure of multiculturalism” and attributes the widespread perception of inefficiency in integration policies to a preference for monoculturalism.

It provides concrete examples to demonstrate how the increasing trend of culturalizing migrant integration has led to the adoption of monocultural policies, which polarize Dutch society and stigmatize certain social groups.

The authors emphasize that multiculturalism has never been genuinely embraced as a normative ideal in this national context. Instead, the legacy of “pillarization” days has been used as a familiar heuristic repertoire to interpret integration policies.

National History as a Tool for Nativism

Duyvendak and Kesic explore the role that representations of national history play in debates over national belonging and the integration of immigrants. They demonstrate that the memory of national history is central to contemporary nativism in three distinct ways.

First, nativism denounces the supposed lack of historical consciousness and recognition of national history, especially among national elites.

Second, nativism values the perception of national history as an essential element of national identity, with varied historical narratives.

Third, nativism uses national history as a political instrument to solve social problems. In Dutch debates, nativists posit that the presumed self-alienation and integration failure of migrants can be corrected by a politically induced historical consciousness of the nation’s past among national citizens.

Notably, nativist sentiment now extends to the national culture of secularity, within which values such as freedom of thought, expression, and sexuality become instrumentalized. Nativists mobilize gender relations, homosexuality, and Christianity to underline Muslims’ incompatibility with Western culture, viewing them as intruders on a secular moral landscape and disruptors of the dream of a unified, secular, and morally progressive nation.

Cultural Christianity is used to differentiate those who belong to the common culture from those who do not, thus creating a threat to the supposedly shared heritage. Right-wing nativist parties have adopted cultural Christianity as a marker of national identity, opposing Islam, and presuming that Muslims do not sincerely adhere to Dutch values, even if they are fully integrated into society.

The Intersection of Nativism and Racism

The book analyses how racialization and racism fuel contemporary nativism. It argues that racism is increasingly framed in cultural terms and that both implicit and explicit forms of racism often arise from underlying nativist logic. In France, Afro-descendance and Muslim religion each negatively impact the perception of national belonging.

Non-White individuals are culturally excluded from the national community as non-natives. Values, beliefs, and perceptions associated with whiteness are closely linked to a dominant national identity that maintains and supports a racial hierarchy with whites at the top.

Nativism and racism, though distinct notions, are often closely allied, with whiteness at the center of the national self-image. In the United States, nativism is accompanied by a new rise in racism, which has played a significant role in waves of American nativism.

Nativism in the Liberal Left?

In contrast to the common focus in literature on nativism and populism, Duyvendak and Kesic extend their analysis beyond right-wing nativist discourses to include nativist trends within the liberal left. They demonstrate how the liberal left portrays right-wing radical nationalism as a threatening difference, thereby reinforcing nativist logic.

While right-wing populist nativism often views national elites as a threat to the nation due to their multiculturalism and support for immigration, nativist currents within the liberal left manifest in the construction of a nationalism based on solidarity but contributing to legitimizing nativist logic in the public space.

The book provides a significant contribution by analyzing the complex relationship between nativism and liberalism. Duyvendak and Kesic show that, although these two currents are theoretically opposed, they frequently overlap in practice. This dynamic, marked by increasing polarization between nativists and proponents of multiculturalism, as well as a declining trust in traditional political institutions, reveals the challenges within contemporary political discourse.

By critically studying the links between nativism and liberalism, as well as the exclusionary practices of certain groups from the national community, the book offers a nuanced perspective on this phenomenon.

In addition to their social diagnosis, Duyvendak and Kesic offer proposals for better understanding the roots of nativism, its underlying logic, and the strategies liberalism can use to counter it. They emphasize the importance of developing alternative narratives that acknowledge cultural diversity and identity issues. Socioeconomic redistribution measures alone are insufficient to address the challenges posed by nativism.

Consideration must also be given to the majority’s affiliations and forging a common identity beyond cultural divides. Political liberalism must promote an inclusive vision, relevant to minorities and majorities. Constructing new narratives must be a dynamic process, able to renew itself according to the evolution of social and cultural contexts.

It is also essential to restore trust at the local level and show the links between local, national, and global processes. Politicians have a decisive role to play in proposing these new narratives that oppose the alarmist discourses of nativists, especially right-wing extremists.

The book invites us to rethink political liberalism in the face of the challenge of nativism and to strengthen social cohesion in a plural and complex world.

Critique and Future Directions

Despite the strengths of Duyvendak and Kesic’s work, certain gaps warrant further consideration. The authors dismiss universalist analyses grounded in causal processes, arguing that such approaches overlook the critical role of perception in explaining nativism.

According to them, objective factors such as migration or economic crises are not enough to explain the rise of nativism. It is rather the perception of these factors that predicts the rise of this ideology. The authors are certainly right when they give preponderance to perceptions rather than objective facts.

This perspective is widely recognized in academic literature. However, the authors mistakenly attribute this universalist stance to social psychologists and prematurely dismiss the valuable insights social psychology offers in understanding the nativist phenomenon.

Numerous studies in social and political psychology have emphasized the role of nativist social identity in shaping perceptions of the threat posed by immigration to certain groups. According to intergroup threat theory, these perceptions are often not grounded in objective realities but are influenced by factors such as stereotypes, prejudices, and biased information, which can distort the actual situation.

Intergroup threat theory further posits that nativism is frequently driven by fears of losing social and economic privileges, as certain groups perceive competition from immigrants or other perceived threats. This theory argues that nativism does not stem from “objective” or “universal” factors but from psychological mechanisms that activate in response to perceived threats. These mechanisms, shaped by subjective fears and biases, often result in reactions aimed more at preserving perceived status than addressing real dangers.

This perception depends, in turn, on specific conditions that make it possible. Some of these studies have also shown the role of nativist supply and the instrumentalization of uncertainty in reproducing nativist anxieties.

Perhaps the problem lies precisely in the fact that Duyvendak and Kesic focused almost exclusively on the supply of nativism and neglected the demand side. By overlooking the role played by nativist population sectors in the nativist dynamic, they fail to explain why the supply of nativism resonates with these sectors. However, it is essential to consider the active role that these sectors play in promoting and propagating nativist ideology.