Shaping the Profession: Towards a Genealogy of Professional Ethics, authored by Tiziana Faitini, delves into the intricate evolution of professionalism and its ethical dimensions. The book blends philosophical, legal, and theological insights to chart the trajectory of the concept of “profession” from Ancient Rome to its pivotal role in modern society. It examines the transformative journey of professional duty, illuminating its profound influence on social identity and status across the ages.

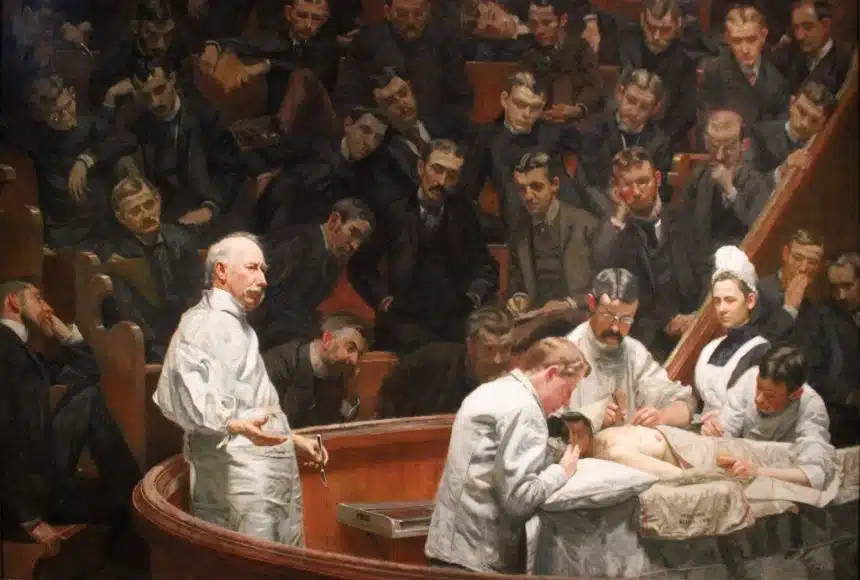

This work goes beyond traditional historical narratives, offering a critical analysis of socio-political thought amid the ever-evolving global labor landscape. It expands its examination to the realms of academia and professional practice in medieval universities, highlighting the political, legal, and economic dimensions of scholarly professions. The discourse on the roles and responsibilities of these professions is brought to the forefront, alongside a detailed study of 18th- and 19th-century literature that shaped the professional conduct of doctors, lawyers, and emerging professional groups, emphasizing the role of occupation in defining social and civil status.

This book is essential for those seeking to comprehend and navigate the complex dynamics of professionalism and ethics in today’s world.

Shaping the Profession thus serves as a comprehensive resource, providing nuanced perspectives on the interplay between the “profession,” socio-political inclusion, and the shaping of citizenship in work-based democracies. It invites readers to engage with the ongoing evolution of professional ethics, underscoring its enduring impact on the fabric of modern society. This book is essential for those seeking to comprehend and navigate the complex dynamics of professionalism and ethics in today’s world.

In the upcoming sections, Tiziana Faitini elaborates on the central ideas of her book, with Michele Nicoletti and Massimo Palma subsequently offering their scholarly commentaries. These analyses provide diverse perspectives on the themes and implications of Faitini’s work, contributing to a comprehensive understanding of its historical and sociopolitical relevance.

Professionalism: From Citizenship to Inclusion

By Tiziana Faitini

In contemporary neoliberal societies, the archetype of the “professional” has emerged as a paramount ideal, profoundly influencing our economic, social, moral, political, and personal realms. This pervasive figure prompts critical questions: What are the origins of this archetype, and how has it become so integral to various aspects of our lives?

Shaping the Profession seeks to explore professionalism as a multifaceted experience. Drawing inspiration from Michel Foucault’s genealogical method, particularly his study of sexuality, it examines professionalism as an interplay among knowledge domains, normative frameworks, and forms of subjectivity. The aim is to trace the historical layers of value attributed to the professional role, scrutinizing its moral, legal, social, economic, and epistemological dimensions.

Professionals have become central figures in numerous discourses, overshadowing the traditional concept of the “worker” that dominated political and sociological debates in the 20th century. The evolving discourse on professional ethics exemplifies this shift, as seen in the burgeoning academic research focused on professional conduct and the proliferation of codes of conduct and norms by professional bodies.

Despite the significant contributions of various scholars, comprehensive historical investigation into the discourse of professional ethics remained absent. This book endeavors to fill this gap, exploring the historical conditions that shaped both the discourse on professional ethics and the concept of the “professional” itself.

The journey of this exploration spans from Ancient Rome to the present, encompassing philosophical, juridical, and theological sources from Italy, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. Adopting a longue durée perspective, the study presents a selective overview of conceptual developments, the interplay of legal, religious, and economic ideas, and the relationship between theory and practice.

The political and philosophical task ahead involves reimagining the vocabulary of socio-political inclusion.

Tiziana Faitini

Max Weber’s interpretation of the Protestant concept of Beruf (vocation) is a pivotal reference in this narrative. Weber contended that modern economic rationality stemmed not from the Enlightenment or secularisation, but from an intrinsic rationalisation within religions, particularly Protestantism and Calvinism. This thesis, though debated, provides a profound insight into the historical and philosophical understanding of professionalism, the philosophy of work, and capitalism.

Yet, the concept of Beruf, despite its analytical strength, does not encapsulate the entire history of the semantic field of professionalism. The term “profession” historically transcended Beruf, encompassing a broader spectrum of meanings related to citizenship, economic activity, and moral and legal duties. This research delineates a nuanced history of the “profession” and its relationship to concepts like “status” and “office,” highlighting its initial association with citizenship and inclusion before its evolution into the realm of economic-acquisitive activity.

This historical perspective sheds light on a key aspect of European social and political rationality: the crucial link between occupation and socio-political inclusion, leading to the contemporary notion of work-democracies and their conceptualisation of citizenship. The role of occupation in determining one’s societal and political status, underscores the profound semantic implications of the profession.

A genealogy of professionalism is not merely a history of professional ethics or an exploration of work’s ethical valorisation and capitalism’s “iron cage.” Rather, it is a critical examination of contemporary socio-political thought and the apparatus of citizenship and political and social rights.

However, this apparatus faces challenges in the current era, marked by dramatic transformations in the world of work due to information technology, increasing employment precariousness, and the erosion of the Fordist model of full employment and work-related welfare. The political and philosophical task ahead involves reimagining the vocabulary of socio-political inclusion. A profound understanding of this historical context is essential for reshaping our work-democracies, redefining social protections, rights, and valorisation of professional duties in a rapidly evolving world.

Work and Citizenship: The Evolving Role of Professionalism in Society

By Michele Nicoletti

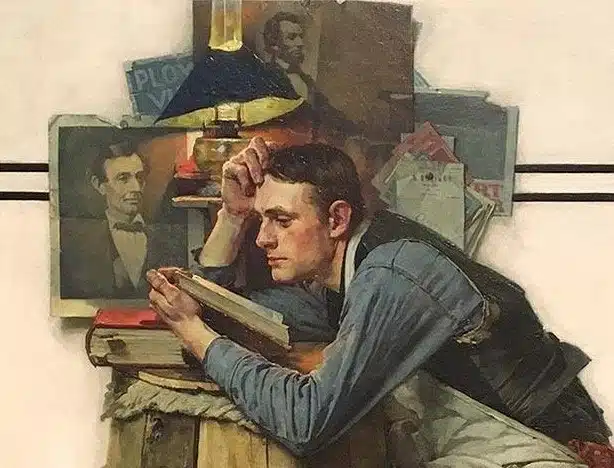

In her seminal work, Tiziana Faitini embarks on a profound exploration of the evolution of professional ethics across Western civilizations, ultimately revealing a vibrant mosaic of individual self-fulfillment and social integration within the realms of work and professional activities. Faitini’s meticulous genealogical study unravels the multifaceted nature of “professionalism” – a concept that, on the surface, appears solely focused on the dedication to excelling in one’s occupation. However, this exploration uncovers a wealth of insights into pivotal themes such as ethical-religious calling, political identity, societal inclusion, and the pursuit of personal dreams and ambitions.

Delving into the complex blend of “vocation” and “profession”, Faitini’s book illuminates a rich tapestry of spiritual, philosophical, political, and legal texts that span over two thousand years. Orations, sermons, treatises, constitutional norms, laws, and ethical codes intricately shaped the human endeavor, be it in mundane labor or extraordinary creative pursuits. From the shared heritage of Medieval Latinity and Christianity to diverse national traditions across Europe, Faitini’s work provides a comprehensive examination of the historical voices of artists, craftsmen, and professionals.

In modern society, the focus shifts from occupying spaces to dominating life-time.

Michele Nicoletti

Shaping the Profession elevates the seemingly narrow subject of professional ethics to a primary focus of philosophical and political discourse, compelling us to revisit the foundational questions about the essence of work and its critical role in connecting the individual to society and the political sphere.

One of the most salient discussions inspired by the text is the role of work and professional activities in the dynamics of political inclusion, particularly epitomized by the concept of citizenship. At first glance, the significance of work in political contexts appears to be a modern phenomenon. Traditionally, societies, from the Neolithic era through the Industrial Revolution, were built upon land occupation, a crucial factor in establishing social and economic structures and political authority. In this view, the “political” emerged from a societal foundation rooted in control over the means of production and coercive power, characteristic of both large and small military land aristocracies.

Whether through republican associations or feudal domination, the pairing of land and military has been the cornerstone of political power and the framework for political inclusion, encompassing both the ruling class and the concept of citizenship. The social embodiment of the “political,” with its attendant concepts, emerged from this foundation, encompassing experiences of territorial control, conquest, and the appropriation of spaces and bodies. This medieval paradigm extended beyond Europe during the modern era through territorial conquests and colonization.

In contrast, and often overshadowed by military dominance, commercial trade and industrial activities evolved, presupposing, and reshaping the notions of material and spiritual appropriation. These activities gradually came to represent a different logic, contrary to that of the “soldier” – the logic of the “bourgeois,” aiming to supplant war with peaceful, rational, and commercial exchanges. Herbert Spencer’s distinction between “militant societies” and “industrial societies” encapsulates this dichotomy.

Militant societies, organized for war, relied on internal cohesion, strict hierarchies, and discipline, often at the expense of individual freedom. Their constant struggle for survival and dominance necessitated material self-sufficiency, protectionism, and aggressive foreign policies. In contrast, industrial societies rechanneled human aggression into productive work, emphasizing the creation of socially beneficial goods and voluntary cooperative efforts over state coercion.

Spencer’s analysis, despite its optimistic view of voluntary cooperation, acknowledges that labor is not a mere antithesis to military activity but rather a sublimation of it. This perspective reveals why industrial production often retains the logic and terminology of warfare. In this context, production becomes the new form of appropriation post-conquest, leading to compulsory conscription and reserve industrial armies. However, the concept of occupation persists – not just in terms of territorial expansion or the extraction of value from human resources but also in the occupation of time. In modern society, the focus shifts from occupying spaces to dominating life-time, blurring the lines between work and leisure, negating idleness through the mobilization of religious and moral philosophies.

This dual aspect – the transformation of aggressive instincts into labor and the transition from spatial to temporal occupation – merits further exploration. The modern political landscape bears the imprints of this evolution. Thomas Hobbes, in Leviathan, articulates the transition from a state of nature to a society driven by industry, not conquest, where the political system aims to recognize, value, and compensate industrial endeavors. This shift towards an industrial society gains further momentum in John Locke’s labor/property theory.

The bourgeoisie era marks a significant departure from the traditional glorification of military valor, highlighting the importance of work and profession in social and political inclusion. This transition bridges the gap between feudal societies, centered around land and military power, and modern individualistic societies. The historical experience of estate societies, with their intricate tapestry of corporations, estates, and a diverse array of activities and professions, plays a pivotal role in this evolution.

The prominence of labor in the constitutionalization of modern states ties back not only to the rise of the bourgeoisie and the industrial proletariat but also to the lasting influence of estate societies and their transition into corporative states in the 20th century. This constitutional journey includes the recognition of the right to work in significant political documents, tracing a lineage from Hegel to fascist corporative states. From a societal perspective, the construction of the modern state results not only from the interplay of landed aristocracies, commercial bourgeoisies, and military classes but also from the influence of professional groups, exemplified by the crucial role of jurists in medieval and modern times.

The work-citizenship dyad, while possessing tremendous liberating potential, also reveals discriminatory tendencies against women, youth, the elderly, and foreigners.

Michele Nicoletti

Shaping the Profession skillfully intertwines groundbreaking developments with enduring continuities, including the persistence of language, metaphors, and military practices. The exaltation of work and industriousness, tinged with activist rhetoric, echoes the traditional narrative of combat and struggle. Carl Schmitt’s 1934 essay highlights the nuanced victory of the “bourgeois” over the “soldier,” not in the context of the passive bourgeois merchant or financier seeking peace for commercial gain, but rather in the image of the producer as the modern “fighter” par excellence.

This perspective frames work not only as a struggle against nature and for value creation but also as a class struggle, retaining a military and militant character from the 1848 revolutions to the Russian Revolution and beyond. Beneath the liberal narrative of a peaceful industrial age supplanting war and violence with trade and negotiation, the military dimension persists, infiltrating all social groups and involving every individual in an existential and social struggle.

The 20th century further intensifies this militarization of labor and remilitarization of politics, with new political leaders often donning military uniforms. Schmitt interprets this as the soldier’s revenge on the bourgeois, yet the process remains highly ambivalent. Work has become a means of inclusion, and despite its military organization, its emancipatory myth endures. The figures of the worker and the soldier walk side by side, mirroring each other, with labor camps paralleling concentration camps. Schmitt himself, distanced from the myth of labor, criticizes the conflation of work with imperial ambition.

In contemporary times, we witness the potential onset of a post-work era, with efforts to transcend the work-centered framework of social and political inclusion. The work-citizenship dyad, while possessing tremendous liberating potential, also reveals discriminatory tendencies against women, youth, the elderly, and foreigners.

Moving beyond the basic dichotomy of worker-citizen or citizen-worker, we are drawn once again to the complex interplay between Bürger and Citoyen. It’s premature to judge whether efforts to dismantle or reshape the connection between employment and citizenship will achieve greater inclusivity. The relevance of job roles remains undiminished in our societal discourse. Global conflicts continue to manifest, increasingly so, in the form of territorial occupations, affecting both tangible and digital realms. Moreover, the pervasive encroachment on our daily lives shows no signs of abating. Tracing the evolution and historical interconnections of work and profession with social and political rights, as this book does, offers a robust foundation for understanding and navigating the ongoing changes in these areas.

Shaping the Profession: Beyond the Traditional Work Paradigm

By Massimo Palma

In the seventh chapter of Kafka’s The Trial, we witness Josef K.’s weariness as he encounters Titorelli, the so-called “court painter.” Titorelli elaborates extensively on his moorland landscape artworks, which, despite their identical nature, elicit varied reactions from purchasers. Amidst the oppressive atmosphere pervasive throughout the novel, Josef K., overwhelmed in the cramped studio of the painter, struggles to focus on Titorelli’s account of his life as an impoverished artist, which Kafka refers to as “professional experiences of the beggar-painter”.

Kafka intriguingly juxtaposes the term “professional experience” with a societal outcast, the “Bettelmaler,” challenging our conventional views of a worker with a notable professional history. The dual identity of Titorelli as both an artist and a beggar diverges significantly from the traditional notion of labor defined by expertise and educational background. Art and begging, as portrayed in the novel, are more akin to leisure (otium) than business (negotium). Yet, Kafka wittily links these concepts, suggesting that true professional insight might lie in the life of the nonconformist, the artist who seeks remuneration for his street art.

Faitini illustrates that being part of a profession is not only about skill but it also shapes one’s identity and contributes to the broader ethical and legal norm

Massimo Palma

In her book, Tiziana Faitini delves into the complex interplay of idleness, instability, and societal judgments about those who embrace such a lifestyle. Faitini’s philosophical and political exploration, bolstered by historical evidence, reexamines the notion of “profession.” Her book endeavors to imbue the age-old idea of professional experience with conceptual and historical depth, influenced by Foucault and the tradition of Begriffsgeschichte (conceptual history). Faitini illustrates that being part of a profession is not only about skill but it also shapes one’s identity and contributes to the broader ethical and legal norms.

Faitini’s work also revisits Max Weber’s concept of the Beruf, using it as a backdrop and conversational reference. She aims to offer an alternative perspective to Weber’s ideas, tracing the evolution of the term “profession” from its Roman roots. The Latin term “professio” originated from “profiteor,” which means ‘to declare officially.’ Initially, it signified subjection to the ruling power. To “profess” began as a declarative linguistic function and evolved over centuries to signify a committed relationship between professionals and their specialized training.

The study delves into the ethics of idleness and its juxtaposition with the sanctity of work.

Massimo Palma

Faitini highlights the multifaceted nature of professions throughout history, from their economic and ethical implications to their cultural and educational aspects. The book explores the interconnection between work ethics and professionalism, underscoring the complex relationship between economic gain and moral obligation in various professions.

In a broader context, Faitini’s study addresses the societal and political dimensions of professionalism. She examines the role of work as a social integrator and profession as its primary agent, discussing the historical evolution of work ethics and the concept of vocation. The study delves into the ethics of idleness and its juxtaposition with the sanctity of work. It explores themes such as the glorification of labor and the bourgeois society’s stigmatization of inactivity. Additionally, the study sheds light on the prehistory of contemporary cognitive capitalism, characterized by the portrayal of the intellectual, often in a precarious state, as an industrious and active “entrepreneur of the self.”

Ultimately, Shaping the Profession is an in-depth exploration of the historical, philosophical, and sociopolitical aspects of professionalism and intellectual work. Faitini’s book offers a nuanced understanding of the role and evolution of professions, inviting readers to reconsider the intersections of work, ethics, and societal norms.