Indigenous Policy and the Strategic Logic of Russian Expansion

Just as Japan and China have both acknowledged the importance of engagement with the Arctic’s indigenous peoples in their respective 2015 and 2018 Arctic policies, indigenous issues also featured prominently in Russia’s updated 2020 Arctic strategy, where they are mentioned at least 17 times as compared to the seven mentions by both Japan and China.

- Indigenous Policy and the Strategic Logic of Russian Expansion

- Frozen Conflict as a Strategy for the Warming Arctic: Hokkaido and the Ainu Homeland as a Contested Military Frontier

- Ainu Recognition and the Geopolitics of the Indigenous Arctic

- Speculation, Historical Claims, and the Doctrinal Framing of Hokkaido

- Russia’s Far East Calculus: Hokkaido, China, and Strategic Vulnerability

- Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

- Bloc Consolidation and Japan’s Strategic Alignment in the Arctic

Intriguingly, Ural Federal University recalls that “[i]n late 2018 the Russian President Vladimir Putin agreed with the proposal to recognize the Ainu as an indigenous people of Russia, which fueled concern among the Ainu living in Hokkaido (because ‘Russians’ might be granted more privileges – for example, group rights to fishing).”

With Moscow’s subsequent commitment to the “preservation of the native lands and traditional ways of life of minority groups” in its 2020 Arctic strategy, and invasion of neighboring Ukraine two years later, one can now reasonably reinterpret Putin’s 2018 recognition of the Ainu as indigenous to Russia as a pretext for yet another territorial expansion – one far from Ukraine, extending Russia’s ongoing eight-decade occupation of the southern Kurils to the island of Hokkaido, with its vast lands, increasingly strategic waters, and seemingly unlimited green energy and data center potential.

Frozen Conflict as a Strategy for the Warming Arctic: Hokkaido and the Ainu Homeland as a Contested Military Frontier

I first learned of Putin’s 2018 Ainu recognition from Jeffry Gayman, an Associate Professor at Hokkaido University on the Research Faculty of Media and Communication and Graduate School of Education (Multicultural Education Course), when visiting Hokkaido to present a guest talk at its Arctic Research Center in 2019 on indigenous foundations of Arctic sovereignty.

After Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, I began to understand Putin’s Ainu recognition through a new, worrisome lens. One that illuminates recent diplomatic and strategic trends – notably Moscow’s diplomatic and strategic alignment with Beijing, and consequent intensification of joint operational activity in and around Japan’s northern territories – in a new and troubling light.

A Russian territorial expansion to Hokkaido could strengthen Moscow’s position relative to both China, should their strategic alignment run its course, and the West.

A war for the eventual “reunification” of the Ainu homeland is thus now easier to envision, much the way the Kremlin perceives its war in Ukraine as a just and necessary war of sovereign restoration, fueling its determination and helping to ameliorate its high toll in losses of troops, equipment, and treasure, much to the surprise of many critics of Putin’s war.

History has shown us time and again that Russia, if anything, can be a determined military opponent, and more than fickler democratic states can stomach steep military losses when the wholeness of mother Russia is perceived to be at stake. Through this lens, a war for the eventual “reunification” of Hokkaido with Russia, and “restoration” of the unity of the Ainu homeland, is not only possible but perhaps even inevitable.

Even if victory seems unlikely in such a war, Russia’s capacity to bog down its opponent in a seemingly forever war of attrition marked by little in the way of battlefield advances at an inexplicably high cost in losses could in fact be Moscow’s end game. Creating a frozen conflict that forever paralyzes Japan and its western allies while holding the line of contact well within a militarily contested island of Hokkaido – and thereby keeping the Northern Sea Route (NSR) open for business as Japan fights for its national survival – could be a logical expansion of Russia’s current war in Ukraine.

With the historic deployment of North Korean troops to the conflict earlier this year, and the expansion of Ukraine’s retaliatory deep strikes to targets in the Russian Far East, such an expansion of Putin’s war to Northeast Asia has in significant ways already begun.

Ainu Recognition and the Geopolitics of the Indigenous Arctic

Is such a scenario imminent? No. But could it nonetheless become inevitable? Perhaps so. At the very least it is something to worry about, and to plan to forestall.

That Russian president Vladimir Putin described the Ainu as an indigenous people of Russia further reinforces Hokkaido’s (and therefore Japan’s) Arcticness, much the way the long presence of indigenous Unangan (Aleut) reinforces the Aleutians’ (and by extension, America’s) Arcticness, and the long presence of Inuit reinforces Canada’s own Arcticness.

This leads us to a necessary reconceptualization of Arctic sovereignty through a converged lens blending Westphalian and “post-Westphalian” precepts (borrowing a term coined by Jessica Shadian on the emergence of a distinctively Inuit polity in the Arctic that possesses traits of both a sovereign and transnational nature, and which I have discussed elsewhere at length.)

Japan does not stand alone, and has its own hand to play, evident in its alignment with the democratic Arctic Council members on indigenous issues, and in its own distinctive whaling diplomacy.

These interesting but much overlooked pronouncements recognizing the Ainu people – whose homeland, since World War II’s end, has been partitioned by Russia and Japan – as indigenous to Russia, certainly caught the attention of Tokyo, and may well have accelerated its pace recognizing Ainu as an indigenous people of Japan, which had been incrementally advancing since 1997.

This left Japan vulnerable to a more pro-active (and, one can argue, more Machiavellian) approach by Moscow on Ainu rights issues, potentially planting a seed for an eventual sovereign claim by Russia over Hokkaido as part of “Russia’s” Ainu homeland, and thereby providing a possible pretext for a subsequent war of “reunification” and “sovereign restoration” with the Ainu conveniently portrayed by Putin as indigenous to, and thus an historical part of, Russia.

Speculation, Historical Claims, and the Doctrinal Framing of Hokkaido

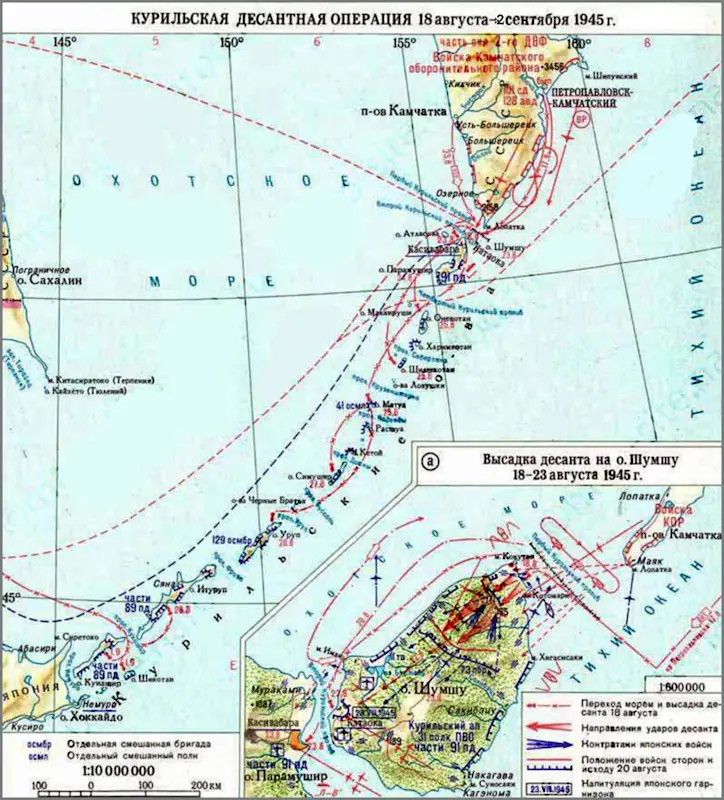

Some have speculated that Putin had been considering Hokkaido for just such a war before selecting Ukraine as his initial target for imperial re-expansion, leaving Hokkaido as a potential second front, with a dusty, unimplemented Soviet-era war plan from the waning days of World War II ready to go.

Indeed, according to a March 1, 2023 article from the International Research Institute on Controversial Histories (“Leave the Ainu issue unattended and Hokkaido will become a second Ukraine”):

“In December 2018, it was reported that Russia’s President Putin intended to acknowledge the Ainu people as indigenous Russians. Furthermore, in April 2022, vice-chairman of the State Duma, the lower house of the Russian Parliament, Sergei Mironov reportedly stated, ‘to certain experts, Russia owns all rights in Hokkaido.’ Also in April 2022, ‘According to Regunam News, political scientist Sergei Chernyakhovsky maintained that ‘Tokyo improperly retains Hokkaido, which was politically Russian territory.’ Referring to the assertion made in the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation between Japan and Russia concluded in 1855, the report stated: ‘There the Ainu people lived. They are the same people that live in Sakhalin, in the suburbs of Vladivostok and in the south of the Kamchatka Peninsula and are one of the peoples of Russia.’ Let us put President Putin’s assertion in the current context. In September 2022, he stated a new diplomatic policy, called ‘Russia’s World’ and stipulated that Russia will intervene in countries in support of Russian inhabitants. And according to another report, Russia planned to militarily intervene in Hokkaido before it invaded Ukraine.”

Amidst the present circumstances in Ukraine, and with Russia’s continued occupation of the entire Kuril Island chain since the final hours of World War II, even if these are not mainstream views, they may nonetheless serve as a harbinger for future concern and consideration. After all, Putin’s interest in conquering Ukraine by force also likely had origins well outside of the mainstream of political, diplomatic and strategic thought before becoming state policy.

Russia’s Far East Calculus: Hokkaido, China, and Strategic Vulnerability

Should Russia turn its attention next to Hokkaido, it will be driven in large part by Russia’s concerns over China’s military rise and the threat Beijing could ultimately present to Russian sovereignty in its vulnerable Far East. While Moscow and Beijing are now closely aligned, it would be shortsighted to presume this alignment will remain enduring given their past enmity and the potential for a future breakup. According to the New York Times, recently acquired and independently authenticated intelligence documents from Russia reveal deep concerns in its FSB counterintelligence community about Moscow’s alignment with Beijing.

These documents also describe Russia’s efforts to counter the many emergent long-term threats China could pose against to Russian interests, including future assertions by China of territorial claims intent on redressing unjust historical treaties that codified imperial Russia’s 19th century expansion onto Chinese-controlled territories: “Mr. Putin and Xi Jinping, China’s leader, are doggedly pursuing what they call a partnership with ‘no limits’. But the top-secret FSB memo shows there are, in fact, limits. … In public, President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia says his country’s growing friendship with China is unshakable — a strategic military and economic collaboration that has entered a golden era. But in the corridors of Lubyanka, the headquarters of Russia’s domestic security agency, known as the FSB, a secretive intelligence unit refers to the Chinese as ‘the enemy’.”

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

As the New York Times further describes: “China is searching for traces of ‘ancient Chinese peoples’ in the Russian Far East, possibly to influence local opinion that is favorable to Chinese claims, the document says. In 2023, China published an official map that included historical Chinese names for cities and areas within Russia. … Russia has long feared encroachment by China along their shared 2,615-mile border. And Chinese nationalists for years have taken issue with 19th-century treaties in which Russia annexed large portions of land, including modern-day Vladivostok. That issue is now of key concern, with Russia weakened by the war and economic sanctions and less able than ever to push back against Beijing.”

Bloc Consolidation and Japan’s Strategic Alignment in the Arctic

A Russian territorial expansion to Hokkaido could strengthen Moscow’s position relative to both China, should their strategic alignment run its course, and the West. But the West has not sat idly by, fearful that Eurasia could consolidate into an increasingly unified regional bloc. In lockstep with its perceptions of a tightening Beijing-Moscow alignment, NATO has expanded rapidly to now include the formerly neutral Nordic states, Finland and Sweden.

And while Arctic North America has experienced new tensions since President Trump’s return to the White House in 2025 – owing to his openly expressed ambition to gain sovereign possession of Greenland (and, at times, Canada as well, in whole or in part) – even this can be seen as a hemispheric consolidation into a singular bloc (formally codified as policy in America’s newly released 2025 National Security Strategy), mirroring the diplomatic and strategic alignment under way in Northeast Asia.

But Japan does not stand alone, and has its own hand to play, evident in its alignment with the democratic Arctic Council members on indigenous issues, and in its own distinctive whaling diplomacy. This diplomacy unites Japan’s whaling heritage and commitment to its preservation with both the commercial whaling states of Iceland and Norway, and the subsistence/indigenous whaling nations of Arctic North America, the United States, Canada and Greenland, finding principles in common beyond their parallel structures of constitutional democracy and commitments to the rule of law to help forge a united front with likeminded nations to its north.

This article is part of a series. Read Part I and Part II for the full analysis.