- The Historical Importance of a Taiwan-Centred Perspective

- Identity and the Politics of Representation

- The Implications of Neglecting a Taiwan-Centred Approach

- The Role of Taiwan Studies

- Reflections on Taiwan Lives: A Social and Political History

- The Title: Lives and Lives

- A Liminal Narrative Structure

- Colonial Histories and Settler Colonialism

- The Question of Postcoloniality

- Taiwan in the World

- Discover Books Featured by Our Authors

- References

Taiwan is a vibrant democracy, an economic powerhouse, and a culturally rich society with deep historical roots (Rigger, 2011). Yet, the study of Taiwan has often been filtered through external perspectives—whether Chinese, Japanese, or Western—rather than from Taiwan itself.

The emergence of civic nationalism, as opposed to ethnically driven nationalism, underscores Taiwan’s unique identity within the global order.

This has profound consequences for academic discourse, policymaking, and global awareness. To study Taiwan on its own terms, rather than as a derivative of another entity, is to engage with its unique history, identity, and sociopolitical trajectories. Ignoring this perspective not only distorts Taiwan’s reality but also contributes to broader misunderstandings in international relations and regional dynamics.

The Historical Importance of a Taiwan-Centred Perspective

The history of Taiwan is layered with colonial encounters, Indigenous narratives, and self-determined politics. From the Dutch and Spanish colonial enterprises of the seventeenth century to Japanese rule (1895–1945) and the postwar Kuomintang (KMT) government-in-exile, Taiwan has been subject to multiple foreign administrations.

Each of these regimes has sought to impose its own version of history and historical development, often marginalising local voices in the process.

A Taiwan-centred perspective acknowledges this complex history while resisting reductionist narratives that frame Taiwan merely as a peripheral extension of China.

As highlighted in my recent book Taiwan Lives (University of Washington Press, 2024) the development of a distinctive Taiwanese consciousness, particularly following the 228 Incident and the lifting of martial law in 1987, demonstrates the island’s capacity for self-determination and nation-building.

The emergence of civic nationalism, as opposed to ethnically driven nationalism, further underscores Taiwan’s unique identity within the global order.

Identity and the Politics of Representation

Studying Taiwan from within Taiwan allows for a more nuanced understanding of its national identity. External interpretations often impose an artificial binary between “Chinese” and “Taiwanese” identity, ignoring the island’s Indigenous communities and its Austronesian heritage.

Taiwan’s identity is not simply a reaction to China; it is a dynamic construct shaped by local agency, migration patterns, and regional interactions.

Studying Taiwan on its own terms highlights the ways in which it has navigated democratic consolidation despite external pressures.

If Taiwan continues to be studied only through a Sinocentric lens, key aspects of its identity—such as linguistic diversity, and postcolonial narratives—will remain underrepresented.

As Taiwan Lives notes, the “start-again nationalism” of the postwar period was not an imitation of Western nation-building but a response to Taiwan’s unique historical conditions.

Su Beng’s Taiwan’s 400-Year History (1986) was one of the first works to challenge the idea that Taiwan’s identity must be exclusively Chinese, instead framing it within broader anti-colonial struggles.

The Implications of Neglecting a Taiwan-Centred Approach

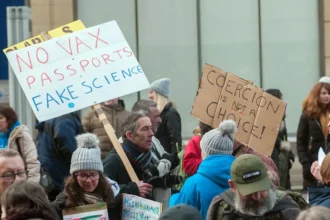

If Taiwan is continuously framed as a product of China, it affects how international bodies, such as the United Nations and the World Health Organisation, interact with it. As demonstrated by Taiwan’s exclusion from the WHO, global institutions often sideline Taiwan’s contributions because they fail to see it as a distinct entity.

This not only undermines Taiwan’s international agency but also hampers global cooperation on pressing issues such as public health and climate change. Similarly, Taiwan’s democratic evolution is often overlooked in discussions that focus solely on its relationship with China.

The Indigenous position in Taiwan’s history has often been neglected in favour of settler-colonial narratives.

The island’s journey from martial law to a thriving democracy is one of the most significant political transformations in modern history. Studying Taiwan on its own terms highlights the ways in which it has navigated democratic consolidation despite external pressures.

The Sunflower Movement, for instance, was not merely an anti-China protest but an assertion of Taiwan’s democratic agency. Taiwan’s economic achievements—particularly its dominance in the semiconductor industry—are frequently discussed in geopolitical terms rather than as a result of Taiwan’s own innovation and policy choices.

The framing of Taiwan as a geopolitical pawn rather than an economic leader distorts the reality of its contributions to global technology and trade. Additionally, a failure to study Taiwan from within results in the marginalisation of Indigenous histories and contemporary struggles.

As Taiwan Lives points out, the Indigenous position in Taiwan’s history has often been neglected in favour of settler-colonial narratives. The process of decolonisation is ongoing, and a Taiwan-centred approach allows for the proper inclusion of these voices in national and academic discourse.

The Role of Taiwan Studies

Taiwan Studies as an academic discipline is crucial for rectifying these imbalances. Unlike traditional Sinology or East Asian Studies, which often subsume Taiwan into broader narratives of China, Taiwan Studies provides a framework that acknowledges Taiwan’s specificity. Institutions that incorporate Taiwan into their curricula without conflating it with China contribute to a more accurate global understanding of the region.

This is particularly important in the social sciences and humanities, where Taiwan serves as a case study for issues ranging from democratic transitions to identity politics. For instance, Taiwan’s Indigenous groups offer key insights into Austronesian migration and cultural continuity. Moreover, Taiwan’s response to authoritarian legacies provides comparative lessons for other post-authoritarian societies. As such, Studying Taiwan from Taiwan’s perspective is not an act of isolationism; it is an act of intellectual integrity.

It acknowledges Taiwan’s complexity and resists the imposition of external narratives that diminish its agency. Without this approach, Taiwan will continue to be misrepresented in international affairs, its democratic achievements will be overshadowed, and its rich cultural landscape will remain underexplored.

To truly understand Taiwan, we must move beyond the constraints of Sinocentric and geopolitically driven narratives. Taiwan is not merely a pawn in global politics; it is a society with its own history, aspirations, and contributions to the world. Recognising this is essential not only for Taiwan but for the broader academic and diplomatic communities that seek to engage with it meaningfully.

Reflections on Taiwan Lives: A Social and Political History

Writing Taiwan Lives: A Social and Political History was an intensely personal and reflective journey. As I explored Taiwan’s colonial, social, and political histories, I found myself drawn to the power of individual narratives in shaping broader historical discourses.

My aim was to present a people’s history, shifting the focus away from top-down state-driven accounts to the lived experiences of those who made, and were shaped by, Taiwan’s historical trajectory. Through these stories, I sought to reflect on Taiwan’s layered colonial past, its movement toward democratisation, and the ongoing complexities of self-determination.

The Title: Lives and Lives

The title Taiwan Lives can be read in two ways: as lives, meaning the life stories of those who have shaped Taiwan, and as lives, signifying the island’s endurance, persistence, and continual reinvention.

Of what layer of colonisation is Taiwan now postcolonial?

This dual meaning was intentional. Taiwan’s history is not static; it is lived, experienced, and constantly evolving.

The stories in this book illustrate how Taiwan continues to live, despite external pressures, colonial legacies, and shifting political landscapes.

A Liminal Narrative Structure

One of the most compelling aspects of my approach in Taiwan Lives was structuring it as a series of interconnected narratives, much like The Canterbury Tales. The book is divided into three thematic sections: A Social History, Pivotal Events, and Being Taiwan.

Each chapter tells the story of a key figure, spanning merchants, diplomats, activists, pop stars, and Indigenous leaders. By using a biographical approach, I wanted to demonstrate how Taiwan’s history is multifaceted, and how identity, politics, and social change intersect in deeply personal ways.

This format reinforces my belief that Taiwan’s history is not a monolithic narrative but rather a collection of multiple, often conflicting stories. Colonial rule, for example, was experienced differently by different communities, and I aimed to reflect this complexity.

Whether through the tale of John Dodd, a British tea merchant in the late nineteenth century, or Fan Yun, a contemporary activist fighting for social justice, I wanted to illustrate that Taiwan’s history is not just a timeline of events—it is a living, evolving experience.

Colonial Histories and Settler Colonialism

In Taiwan Lives, I explore Taiwan’s history within the broader framework of settler colonialism, tracing the island’s multiple colonial layers from the Dutch in the seventeenth century, through Qing expansionism, to Japanese imperial rule, and the postwar period of Nationalist governance.

I make a distinction between Taiwan’s settler colonial history and traditional metropole-colony relationships. Unlike European colonial outposts where settlers often returned home, Taiwan’s colonisation was structural and ongoing. The arrival of Chinese settlers under Qing rule, followed by Japanese imperial strategies of ethnic division, produced complex and enduring power dynamics that continue to influence Taiwan’s political discourse today.

One of my primary goals was to challenge the notion of a singular Taiwanese identity. I wanted to illustrate how the experience of being “Taiwanese” has evolved in response to shifting colonial frameworks. My discussion of Indigenous communities, often sidelined in mainstream histories of Taiwan, was particularly important in revealing how Indigenous identity has been both marginalised and politicised within Taiwan’s nation-building process.

The Question of Postcoloniality

A central question running through Taiwan Lives is whether Taiwan can be considered a postcolonial society. I ask, “Of what layer of colonisation is Taiwan now postcolonial?” This question underscores the island’s continued geopolitical ambiguity, particularly in relation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Unlike Korea, which was able to construct a national identity following Japanese colonial rule, Taiwan was placed under the governance of the Republic of China (ROC) after 1945, a regime that would within a few years find itself in exile. The White Terror period (1947–1987) marked another form of colonisation, this time from within, as the KMT sought to suppress local identity in favour of Chinese nationalism.

By incorporating personal narratives from the White Terror period, including those of Su Beng, a Marxist revolutionary, and Chen Chu, a political prisoner turned Kaohsiung mayor, I aimed to illustrate how authoritarian rule shaped Taiwan’s political consciousness.

The transition to democracy in the late twentieth century is explored as both a rupture and a continuation of previous struggles for autonomy. The Sunflower Movement (2014) further situates contemporary Taiwanese nationalism within the broader historical context of resistance against external control.

Taiwan in the World

One of my aims in writing this book was to challenge the oft-repeated metaphor of Taiwan as a “shrimp between two whales” (China and the United States). Instead, I argue that Taiwan’s significance must be understood on its own terms. By tracing Taiwan’s integration into global trade networks from the Qing period through the twenty-first century, I sought to position the island as a central player in regional and global economies. This perspective is crucial in countering narratives that reduce Taiwan to a pawn in US-China relations.

Discover Books Featured by Our Authors

Moreover, Taiwan Lives interrogates the limitations of existing academic frameworks in studying Taiwan. I critique the tendency to place Taiwan within Sinological studies, arguing that such an approach fails to account for the island’s unique colonial history and Austronesian heritage. Instead, I advocate for an interdisciplinary approach that engages with Taiwan’s Pacific and Austronesian connections, broadening the scope of Taiwan Studies beyond its historical ties to China.

Taiwan Lives is, at its core, a deeply personal reflection on Taiwan’s past and present. By foregrounding individual narratives within broader historical structures, I sought to convey the complexity of Taiwanese identity and its contested histories.

My research, combined with an engaging storytelling approach, makes this book not just an academic contribution but also a statement—to borrow from Shelly Rigger—about why Taiwan matters. What sets Taiwan Lives apart is its refusal to offer a singular conclusion. Instead, it embraces Taiwan’s historical ambiguities, allowing readers to grapple with the island’s contested past and uncertain future.

References

Alsford, N.J.P. (2024) Taiwan Lives: A Social and Political History. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

Rigger, S. (2011) Why Taiwan Matters: Small Island, Global Powerhouse. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Su Beng (1986) Taiwan’s 400 Year History: The Origins and Continuing Development of the Taiwanese Society and People. Washington: Taiwanese Cultural Grassroots Association