Religion has returned to the global stage—not just as a source of identity or mobilization, but increasingly as a tool of statecraft. As emerging powers and established states alike seek new ways to advance their geopolitical agendas, religious soft power has become a vital, if understudied, component of international relations.

- Religion as a Source of Legitimacy and Identity

- Exporting Faith: Institutions, Networks, and Cultural Centers

- Contested Authority: Competing Religious Narratives

- Domestic Drivers of Religious Diplomacy

- When Soft Power Turns Sharp

- Religion and World Order in Transition

- Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

- Conclusion: Taking Religion Seriously in Global Affairs

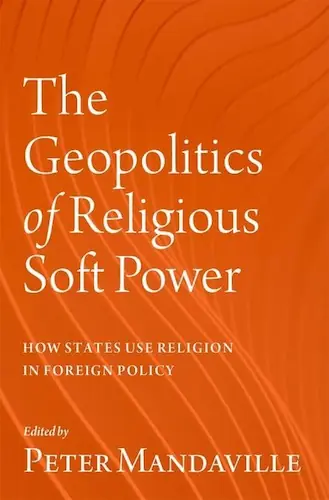

In our edited volume, The Geopolitics of Religious Soft Power: How States Use Religion in Foreign Policy (Oxford University Press, 2023), contributors examine how governments deploy religious symbols, institutions, and narratives to legitimize their authority, shape perceptions abroad, and compete for influence. This article draws out key thematic insights from the volume, showcasing how religion is used across world regions—from strategic messaging in Russia and India to nation-branding in Jordan and Indonesia.

The contributors to The Geopolitics of Religious Soft Power collectively argue that it is time to take religion seriously as a tool of statecraft.

The strategic deployment of religion or religious discourse by states in the realm of world affairs is by no means a new phenomenon. For example, during the Cold War the United States government found geopolitical utility in supporting religious causes and partnering with religious institutions (such as the Catholic church) to counterbalance Soviet influence in multiple world regions. So while not entirely nouveau, the trend we see today represents a significant shift in the range of world powers partaking in the geopolitics of religion. A number of patterns have begun to emerge that allow us to understand the key dimensions of religious soft power.

Religion as a Source of Legitimacy and Identity

Across multiple cases, religion emerges as a powerful vehicle for legitimacy and identity construction. In Russia, President Vladimir Putin has cultivated a close relationship with the Russian Orthodox Church, leveraging its symbolism and messaging to project Russia as a defender of traditional values and a civilizational alternative to the West.

This effort can be viewed as an expansion of Putin’s “Russian World” (Russkiy Mir) project beyond the ethnolinguistic and cultural borders of Russia, Slavic society, or Orthodox Christianity. Religious soft power provides the Kremlin with a platform for building solidarity on the basis of purportedly shared “family” and conservative values, and to position Russia geopolitically as their champion. Similarly, the Modi government in India has infused Hindu nationalist narratives into its foreign policy, advancing a vision of India as a culturally distinct and spiritually rich global actor.

Even secular democracies such as Brazil have seen the instrumentalization of religion. Under Jair Bolsonaro, Christian nationalist rhetoric became central to the articulation of Brazil’s national identity and its engagement with conservative networks abroad—particularly evangelical and Pentecostal communities in lusophone Africa. These examples suggest that religion is not merely a residual or reactive element of state identity, but an increasingly proactive dimension of nation-building and geopolitical signaling.

Exporting Faith: Institutions, Networks, and Cultural Centers

Religious soft power is frequently operationalized through the export of institutions and networks. Türkiye’s Directorate of Religious Affairs, or Diyanet, for example, has emerged as one of the world’s most active state-backed religious bureaucracies, building mosques, training imams, and disseminating religious education across Europe, Africa, and Central Asia. Morocco has adopted a similar model, establishing religious training centers for West African clerics in Rabat and Fez as part of its Africa strategy.

Religious diplomacy is often an extension of domestic governance.

Given the Chinese Communist Party’s traditional antipathy towards religion, Beijing’s promotion of Buddhism—particularly in the Xi Jinping era—seems deeply counterintuitive.

This effort has involved not only investment in domestic religious revival but also targeted outreach to Buddhist communities in Sri Lanka, Nepal, and Southeast Asia, framed as part of its Belt and Road Initiative. These initiatives reflect a growing awareness among policymakers that religious institutions can serve as vectors of cultural affinity, ideological influence, and political alignment.

Contested Authority: Competing Religious Narratives

Religious soft power is often adversarial, as states seek to assert their preferred interpretations and marginalize rivals. Iran’s use of Shi‘i theology in its foreign policy places it in direct competition with Sunni-led narratives emanating from Saudi Arabia and Egypt, as well as with alternative Shi’i authorities in Iraq.

But notably, Tehran is also able to draw on historical Shi’i experiences and symbols of oppression to build ties with non-Muslim (and non-religious) social movements focused on countering neoliberal hegemony in countries as diverse as Venezuela and Thailand. Jordan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia have each promoted themselves as champions of ‘moderate Islam,’ yet their respective interpretations differ in content and intent.

In the Buddhist sphere, China’s state-led appropriation of religious heritage frequently clashes with India’s framing of itself as the historical home of the Buddha. What emerges is a global contest not only over religious symbols, but over who gets to define authenticity and orthodoxy in a pluralistic religious landscape.

Following international relations scholar Gregorio Bettiza, we might think of this as competition for what he terms “sacred capital,” namely the capacity some countries have to leverage their historical ties to particular faith traditions to support their geopolitical goals.

Domestic Drivers of Religious Diplomacy

Many cases in the volume show that religious soft power begins at home. Domestic religious politics—whether aimed at regime consolidation, elite consensus, or societal control—often shape the nature and scope of international religious outreach.

Indonesia’s promotion of ‘moderate Islam’ on the world stage reflects ongoing tensions between its traditionalist Islamic networks and more conservative movements. Similarly, Morocco’s export of Maliki Sunni Islam is closely tied to the monarchy’s effort to preserve religious authority under the king.

These examples demonstrate that religious diplomacy is often an extension of domestic governance, where national religious hierarchies are projected abroad as a means of stabilizing internal political order.

When Soft Power Turns Sharp

While religious soft power is often framed in terms of cultural diplomacy and constructive engagement, several contributions warn of a darker undercurrent.

What some describe as ‘religious sharp power‘ involves using religious narratives and networks to foment division, undermine pluralism, or spread disinformation. Russian support for Orthodox-aligned groups in Eastern Europe, its ties to right-wing Christian actors in the U.S., and its mobilization of ‘traditional values’ rhetoric are all examples of this phenomenon.

Similarly, efforts to instrumentalize religion in Myanmar, Sri Lanka, and parts of South Asia have been implicated in communal violence. These cases show how religion can become a powerful instrument not just of attraction, but of coercion and control—particularly when deployed with nationalist or authoritarian intent.

Religion and World Order in Transition

In a world increasingly defined by multipolarity, normative pluralism, and ideological flux, religion is poised to play an even greater role in shaping international alignments. The Abraham Accords, while framed in secular diplomatic terms, carried implicit religious messaging about interfaith cooperation.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

In other arenas, shared religious values have facilitated transnational alliances across regions—for example, conservative Evangelical groups in the U.S. and Latin America partnering with Orthodox actors in Eastern Europe.

These emerging alliances challenge older models of civilizational conflict by showing that religious affinity may now be operating across, rather than within, traditional blocs. This evolution suggests that future analyses of global order must pay closer attention to the religious dimension—not only as an identity marker, but as an active axis of power.

Conclusion: Taking Religion Seriously in Global Affairs

The contributors to The Geopolitics of Religious Soft Power collectively argue that it is time to take religion seriously as a tool of statecraft. Whether viewed through the lens of legitimacy, diplomacy, competition, or disruption, religion is increasingly central to how states define their interests and pursue their goals.

As we move further into an era where identity and values rival economics and security as pillars of foreign policy, understanding religious soft power will be essential for scholars, practitioners, and the broader public. This volume is a call to incorporate religion more fully into our analytical toolkit—and to do so with both nuance and rigor.