Exploring Fictional Portrayals of the Haitian Revolution

As a literary and intellectual historian, I have spent a large part of my career focusing on how fictional portrayals affected the way that people living in the 18th and 19th centuries understood the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804).

- Exploring Fictional Portrayals of the Haitian Revolution

- Unveiling Jean-Louis Vastey and Black Atlantic Humanism

- Haiti’s Foundational Role in Anti-Racism and Human Rights

- Re-examining the Life of Henry Christophe

- From Fiction to Reality: Depictions of Christophe

- Honoring a Complex Legacy: Writing Christophe’s Biography

In the pre-twentieth century, for ill or for good, a lot of people learned history from reading historical novels. An analogous example is how people often learn (or at least think they do) about big historical events from watching movies, like Amistad or Saving Private Ryan or Schindler’s List.

Haitians gave us the tools to understand what undergirded both the colonial system and the terrible regime of slavery: racism and white supremacy.

And in my first book, Tropics of Haiti (2015), I tried to identify patterns in fictional writings that led to distinctly traceable (and highly racialized) representations of the Haitian Revolution in historical writings. While I have remained interested in this question—in 2022, I published Haitian Revolutionary Fictions: An Anthology with Grégory Pierrot and Marion Rohrleitner, which is a massive publication containing excerpts of more than 200 fictional writings about the Revolution—I have also always been attracted to studying lives.

Unveiling Jean-Louis Vastey and Black Atlantic Humanism

In my second book, Baron de Vastey and the Origins of Black Atlantic Humanism (2017), I turned to studying one of early nineteenth-century Haiti’s most prolific and understudied authors: Jean-Louis Vastey (1781-1820), who was made a baron in the Kingdom of Haiti in 1814 and served as one of the most prominent secretaries of Haiti’s first and only king, Henry Christophe (1767-1820).

During his life Vastey published at least eleven book-length works within a span of only 6 years (1814-1820). My literary biography of him traces how his oeuvre, which includes the first full-length history of the Haitian Revolution written by a Haitian, contributed to anti-racist, anti-slavery, and anti-colonial thought, leading the way in a tradition of Black Atlantic Humanism that also includes Phillis Wheatley, Maria Stewart, Frederick Douglass, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Aimé Césaire, and Toni Morrison.

The freedom from slavery that Haitians instantiated as a human right still lives on today.

I took up the themes of Haiti’s contributions to anti-racist, anti-slavery, and anti-colonial thought in a more systematic way in Awakening the Ashes: An Intellectual History of the Haitian Revolution (2023).

With this book, I really wanted to show how the Haitian Revolution unfolded through Haitian eyes, on the one hand, and to explore the political logics the revolutionaries developed to drive it forward in their quest for freedom from slavery and independence from France, on the other hand.

The book examines the writings of the revolutionaries themselves like Julien Raimond, Toussaint Louverture, Jean-Jacques Dessalines, and Henry Christophe, but it also looks at how nineteenth-century Haitian historians made sense of the Revolution in the long wake of its aftermath in independent Haiti.

I follow the story of the revolution and independence beginning with the resistance of the indigenous population of 15th-century Ayiti (renamed Hispaniola by Christopher Columbus) and how the freedom-fighters of Saint-Domingue (as Haiti was called under French rule in the 17th and 18th centuries) took inspiration from the struggle of those they called “the first Haitians.”

Haiti’s Foundational Role in Anti-Racism and Human Rights

When Haitians declared their official independence from France on January 1, 1804, they renamed the island Haïti, after its indigenous appellations, Ayiti, and independent Haiti subsequently became the first country to permanently abolish slavery and the slave trade.

What is less well known than even this often-ignored fact is that Haitians banned colonialism and imperialism in their first constitution, and that in 1807, the Haitian government, through the editor of northern Haiti’s official newspaper, Juste Chanlatte, put out the first statements of any country in the world declaring slavery and the slave trade crimes against humanity.

The Haitian writer Baron de Vastey also coined the term white supremacy in 1814, long before it appears in any Spanish, French (from France), or English language text, and the writer and historian Charles Hérard-Dumesle coined the term racism in 1824. The freedom from slavery that Haitians instantiated as a human right still lives on today, when we trace the links between the transatlantic abolitionist movement in the 19th century and modern human rights, for example, but Haitians also gave us the tools to understand what undergirded both the colonial system and the terrible regime of slavery: racism and white supremacy.

Re-examining the Life of Henry Christophe

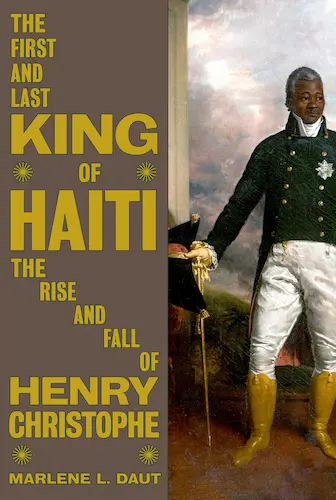

My newest book, a biography called The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe (Knopf, January 2025), might seem like a true divergence from my prior writing.

I pursue what is in some ways a fairly traditional cradle to grave biography, but one that also has implications for how biographies are written: I take the reader behind the scenes and let them know what all the conflicting accounts say, holding back judgment, since in many cases it is impossible to make an objective decision about who was right.

I also further elaborate on Christophe’s radical influence over Haitian revolutionary and post-revolutionary political ideas— indeed, both Chanlatte and Vastey published under the state press created by Christophe to combat racist and stereotypical portrayals of Haiti, on the one hand, and to spread anti-slavery, anti-racist, and anti-colonial ideals across the world, on the other.

Instead of focusing on his life, I could have turned to discussing fictional representations of Christophe, which are legion and mostly reflect demonization of him.

From Fiction to Reality: Depictions of Christophe

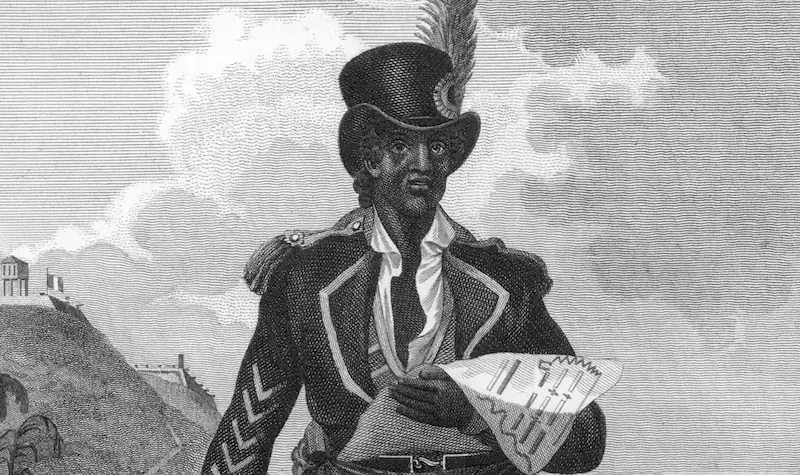

In fact, I begin the biography with a prologue that has a highly literary quality to it, in that I discuss the many, many attempts to portray Christophe’s life on the page and the stage from the nineteenth-century to the present.

I take readers from British author J.H. Amherst’s Christophe, King of Hayti, staged in London’s Coburg Theatre throughout the 1820s, to the Black playwright William Edgar Easton’s Christophe, a Tragedy (1911), which starred Henrietta Vinton Davis, to Rex Ingram’s portrayal of the Haitian king in William Dubois’s Haiti: A Drama of the Black Napoleon, to Orson Welles’s 1936 staging of Macbeth with an all-Black cast that Welles says was inspired by Christophe’s life and which earned the production the nickname “Voodoo Macbeth,” to more recent attempts to stage his life by Derek Walcott (1950) and Aimé Césaire (1963).

If we hope to understand Christophe’s life and death, we must ultimately turn away from the fictional portrayals.

Of course, the author who most infamously tried to fictionalize Christophe’s life was the Swiss-born Cuban author Alejo Carpentier, whose highly popular novel The Kingdom of this World (originally published in Spanish in 1949) has led to a generation of people who continue to encounter Christophe’s story, but who often seem to confuse fiction for history after reading Carpentier’s completely invented portrait of the Haitian king.

But what I try to make clear to readers at the outset of the book by first introducing them to the vast fictional corpus of representations of Christophe—one that also includes John Vandercook’s Black Majesty (1928) and a 1983 Mexican comic book inspired by it called Fuego: Majestad negra, distributed all over Latin America— is that if we hope to understand Christophe’s life and death, we must ultimately turn away from the fictional portrayals.

Honoring a Complex Legacy: Writing Christophe’s Biography

Honoring the story of someone’s life by writing their biography is not just about describing what they did, where they went, where they came from and who they knew, and calling it the truth.

It also means trying to figure out what motivated that person; it means trying to locate what they hoped and dreamed for; it means trying to understand what caused them pain and what caused them joy; it means describing both their successes and their failures. Influenced by the ideas of Arlette Farge in The Allure of the Archives, I felt a responsibility to try to understand Christophe beyond caricature and cliché, as a real human person, who was not larger than life.

I wanted to get to the heart of his experiences as a child and as a revolutionary, to his role as a father, a husband, and a friend, and ultimately, to the complicated story of how he became king. This meant consulting the numerous forms of writing he left behind and those of his family, his friends, and even his enemies and political rivals.

Neither hagiography nor villainization, neither lionization nor an apology, I take readers through the twisting and winding fate of a man most likely enslaved at birth, separated from his mother at a young age, who participated in two revolutions —the American Revolution at the Battle of Savannah at age twelve and the Haitian Revolution— and whose wholly unlikely path to leadership led him to have it all and then lose it all.

A lot of things had to happen to create the circumstances for Christophe to become Haiti’s first and last king —the man who oversaw construction of Haiti’s famous Citadelle Laferrière, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the largest fortress in North America, which has been widely hailed “the eighth wonder of the world”— but to get to those stories, you’ll have to read the book.