Up until the 1990s populism was seen predominantly as a phenomenon of developing regions of the world. But with changes in liberal Western polities in the last few decades, the concept moved from the “periphery” of world politics (such as Latin America and South Asia) to the “core”.

- From the Periphery to the Core of Political Analysis

- Practical Perspectives on Populism

- Populism as Practical and Pragmatic Majoritarianism

- Populism’s Informal Social Contracts and Tactical Governance

- Populism as a Reciprocal Relationship of Power

- The Role of Clientelism in Populist Coalitions

- Populism’s Fragile Relationship with Democracy

- Populism’s Ambivalent Stance on Equality and Hierarchies

- The Mixed Legacy of Populism: Progress and Perils

Researchers started to deploy the concept to analyse the institutionally robust democracies of the West. They used populism to identify radical right and left forces that challenged the liberal arrangements in the West.

Populism is an “informal social contract” in which populist politicians immediately please unprivileged masses in return for electoral support.

Gradual personalization of politics as well as the rising anti-establishment sentiment and discourses have facilitated the deployment of the concept of populism to analyse Western democracies.

From the Periphery to the Core of Political Analysis

When researchers in established liberal democracies started to deploy the concept to study Western politics they focused on discourses in electoral politics. Positivistic methodologies and populism’s peripheral position in remarkably institutionalized liberal democracies led scholars to focus on “words as data”.

Scholars with a less Euro-centric focus tended to underline what populists “do” instead of what they “say”.

This was all too understandable since there was very little opportunity to see populism at work in government in Western political systems. Thus, analyses deploying the concept of populism usually ended up with issues of measurement and operationalization. Scholars confined their examinations to the electoral sphere.

These developments certainly provided researchers with robust and comparative definitional instruments -such as the one proposed by the seminal article of Cas Mudde. However, this same “conceptual sensitivity” usually deprived the researchers of an interpretive perspective. Researchers embracing Euro-centric definitions of populism usually turned a blind-eye on the interplay between populist elites and audiences and the broader power relations that populist incumbents establish among ordinary citizens, local and national economic elites and the political class.

Practical Perspectives on Populism

The analysis of populism in other world regions, however, developed more practical understandings of the phenomenon. Scholars like Laclau, Weyland and Ostiguy have focused on cases of populism in Latin American political systems that are close to power or in office.

This is why these scholars did not limit their examinations with “words” and started to focus on populist ways of mobilization, leadership and socio-cultural praxis. In other words, scholars with a less Euro-centric focus tended to underline what populists “do” instead of what they “say”. Thus, these scholars were more materialistic in certain respects compared to the ideational approaches to the phenomenon which see populism as primarily pertaining to the realm of language.

When viewed from a global perspective, however, populism is always about leadership and the way/style through which politicians appeal to masses. Populism does not only materialize in the “spoken and written words”, but it is something “done”, something fundamentally material and embodied.

Thus, there was a solid point when Weyland strongly emphasized the critical role of leaders in the phenomenon. He was also aware of the practical, material and ocular-centric orientation of populism. Similarly Ostiguy, mainly based on his observations on Argentine Peronism in 1990s, emphasized the socio-culturally relevant styles of populists more than what they talk about in their campaigns.

Populism as Practical and Pragmatic Majoritarianism

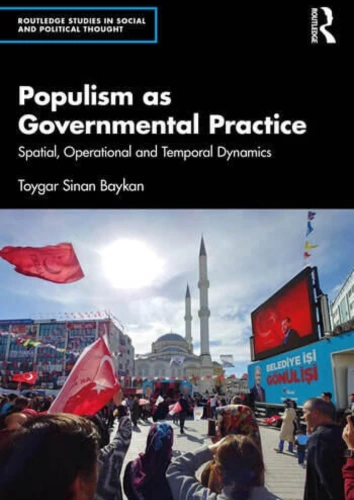

In a recent book titled Populism as Governmental Practice (PGP), by following this practical orientation of the strategic and socio-cultural approaches, I took a further step to understand the praxis of populism. As a multifaceted and multi-layered phenomenon, populism is about ideas and discourses only at the most superficial level.

Populism is a phenomenon of power, and, like the concept of power itself, it always requires a relationship.

But the practical orientation of populism that scholars like Weyland and Ostiguy drew attention to is key if we are going to understand the impact of populism on ordinary people in distinct corners of the world as a phenomenon of power.

In PGP I propose to understand populism as “the practical proclivity of weak authorities and political contenders to personalism, informality, tactics and responsiveness (in spatial, operational and temporal terms) that is appealing to the short-term material and symbolic expectations, interests and tastes of supporting unprivileged majorities” (p. 250). In short, when viewed as a praxis, populism is a practical and pragmatic majoritarianism.

Populism’s Informal Social Contracts and Tactical Governance

Despite all the rhetorical bravado that populism engaged in opposition (like their so-called adversity to corruption and immigration), once in power, populist incumbents are usually in loose control over time and space. They are in fact “weak authorities” trying to respond to multiple problems and powerful elite opposition with limited financial, organizational and human resources.

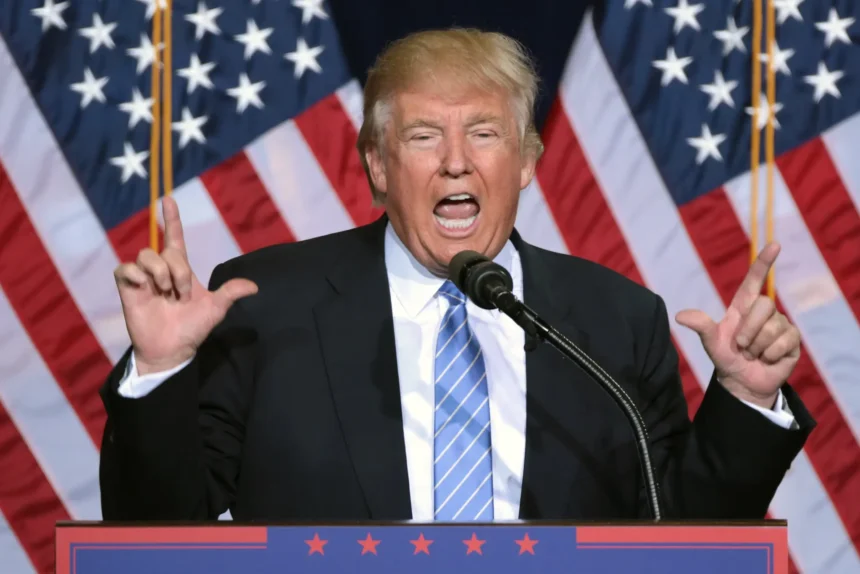

This results in their engagement with short-term, informal, and often tactical policy decisions and implementations. This practicality, in fact, amounts to an “informal social contract” between populists and their supporters when it comes to make critical policy decisions and implement them. I demonstrate many examples in the book but just to show the relevance of “pragmatism” of populism with an up-to-date example it suffices to look at Donald Trump’s recent manoeuvres regarding immigration.

Following Musk’s sensitivity regarding the highly skilled immigrants, Trump declared that he “has always liked the visas, […] have always been in favour of the visas”. Thus, populism is not racism or a strictly xenophobic ideology. It is unprincipled hegemony based on informal consensuses among politicians, parts of the supporting business class and unprivileged majorities.

Populism as a Reciprocal Relationship of Power

In PGP I also show that, as a governmental and political practice, populism is always a game of two (or more). Populism is a phenomenon of power, and, like the concept of power itself, it always requires a relationship. Thus, there is no point in talking about populism if there is no meaningful connection between political elites and their supporters (from rich and poor segments of population) based on material and symbolic reciprocity.

From this perspective, a furious speech on TV based on the separation between “pure people” and “corrupt elite” is far less populist (or only superficially populist) compared to a government that is turning a blind eye to the makeshift residences of urban poor constructed on public land (examples of which can be seen in settings as different as Brazil, Turkey and India).

Supporters of populism tolerate the concentration of power at the top which even borders autocratic rule.

Or, from the perspective developed in the PGP, what is more populist than a transgressive style of a particular politician is the expansion of higher education to such an extent that unprecedented numbers of poor people can get higher education, although in mediocre quality. The exchange here is clear: populism is an “informal social contract” in which populist politicians immediately please unprivileged masses in return for electoral support.

Even under the impact of neoliberalism, alongside satisfying symbolic needs through populist discourses and styles, populists do not shy away from quickly satisfying the material needs of large sectors of their society too through imprudent official social policies as well as via more informal methods, mostly at the expense of long-term costs.

The Role of Clientelism in Populist Coalitions

This is usually done through the participation of a third party in populist “informal contracts”. Supportive businesspeople with vested interests in politics and with populist ideational proclivities support populist politicians’ struggle to satisfy the needs of large majorities: privileges provided to these businesspeople turn into clientelistic benefits for masses and clientelistic benefits for masses turn into votes for populists even under the impact of neoliberalism.

And of course, votes for populists turn again into further privileges for supportive businesspeople. While such mutual relationships of convenience may be perceived with an understandable scepticism, from a broader perspective, this is what makes populism counterintuitively a coalitional, and ultimately, a pluralist phenomenon. At least this is what we see in the Global South.

Thus, despite warnings in the contemporary scholarship, in PGP, many examples testify to the fact that the boundary between populism and especially -what I call in the book-“systematic mass clientelism” is, to say the least, highly porous. Clientelism at a mass level under competitive politics becomes a natural extension of populist politics, especially under the circumstances of neoliberalism in the Global South.

Populism’s Fragile Relationship with Democracy

This inevitably brings us to the relationship between populism and democracy. Alongside its deteriorating impact on institutions and liberal component of “liberal democracies”, especially in power, populism’s proclivity towards clientelism too may undermine democracy. When clientelistic implementation of a populist ruling party surpasses a level that transforms clientelistic operations into coercion this usually marks the end of democracy.

The story ends up with a transition to a hegemonic party autocracy. But this also means that populism disappears since it is the child of competitive politics. When clientelism turns into coercion and effectively eliminates alternative choices for the citizenry there is no need to engage in the niceties of populism that is appealing to the majorities. Populism disappears completely when clientelism starts to complement more overt forms of coercion.

Populism’s Ambivalent Stance on Equality and Hierarchies

Today there is a consensus on the fact that populism is independent from the left-right divide. This raises the question of the position of equality within the context of populism. While the populist discourses in fact adhere to a fictive equality because of populists’ belief in the “volonté générale” as the basis of legitimate politics, from a more practical point of view that is considerate to the dynamics of leadership and governance, it is hard to say that populism is uncompromisingly pro-equality.

When it comes to the procedural aspects of democracy, no populist would object to political equalities. But the role of leadership, populists’ tendency towards immediacy and speed usually leads populist politicians and supporters to embrace personalistic modes of leadership. Thus, supporters of populism tolerate the concentration of power at the top which even borders autocratic rule. It can even be argued that, in many contexts, populists do not have any problem with economic inequalities either if they view them as legitimate. For example, an American populist in 1890s would not object to a fortune made in a “productive” industrial business.

Thus, instead of being a “visionary” worldview that aims for absolute equality through systematic intervention, populist politics “in practice” usually has no problem with given economic, social and political hierarchies as long as they are viewed fair through common sense judgements. Masses supporting populism have no problem with the fact that their representatives come from the richest strata of their societies.

Examples like Silvio Berlusconi, Thaksin Shinawatra and Donald Trump are sufficient for confidently making such a point. Thus, as Paul Taggart emphasizes, populism is a phenomenon in which the most ordinary people are led by the most extraordinary leaders. In short, supporters of populism are not categorically against inequalities and hierarchies: they are only against what they perceive as unjust hierarchies. I would even dare to say that despite being orthogonal to the left-right distinction, due to its proclivity to strong leadership and traditional hierarchies and culture that are deemed as “fair” and “native”, populism always has a slightly right-wing inclination.

The Mixed Legacy of Populism: Progress and Perils

Ultimately populism leaves a mixed record behind where it prevails. On the one hand, especially in deeply elitist, oligarchic and exclusionary political systems, it incorporates the previously excluded and belittled sectors of population to national politics. This also means that populism, to a certain extent, amends material inequalities stemming from elitist political and economic arrangements.

And populism does this quickly through formal and imprudent social policies (as Weyland notes) as well as through systematic informal redistribution based on mass clientelism. Nevertheless, all these processes run by populism in power have their dark sides. When dealing with oligarchic and elitist arrangements to “give the control back to the people” populism usually throws the baby out with the bathwater. Populism’s attempt to incorporate popular sectors to national politics usually results in further decline of institutions in settings which are already institutionally weak.

Thus, when facilitating a sense of participation among the populace, populism effectively undermines check and balance mechanisms. More importantly, when satisfying the material and symbolic needs of majorities with speed and will, inevitable short sightedness of populism results in many long-term problems in different realms of policy. Poorly thought redistribution and clientelism ironically results in poverty; penal populism that satisfy the urgent expectations of law and order results in injustice and chaos; rapid expansion of higher education ends up with large populations with mediocre education and deep sense of deprivation etc..

Yet, despite all of these drawbacks, from a global perspective, as a sort of democratic “emergency rule”, populism helped many nations across the globe to swim on the surface of a sea of multiple crises such as poverty, lack of education, lack of order, security and political legitimacy, ethnic and sectarian divisions etc. Ultimately, maybe it is time for researchers and analysts to take populist forms of democracy and governance as the “global rule” with its darker and brighter consequences while thinking about liberal democratic Western experience as a valuable historical “exception”.