Excerpt from Animals, Robots, Gods: Adventures in the Moral Imagination, by Webb Keane. First published in Great Britain by Allen Lane, an imprint of Penguin Books, © Webb Keane 2024. Published in the United States, its dependencies, Canada, and the Philippines in 2025 by Princeton University Press, © Webb Keane 2025.

Chatbots and the New Forms of Love and Desire

Uncanny things have been happening in the borderlands between humans and non-humans. In August 2021 the Washington Post reported on the growing popularity of extraordinarily sophisticated computer dating apps and chatbots among young Chinese women:

As Jessie Chan’s six- year relationship with her boyfriend fizzled, a witty, enchanting fellow named Will became her new love. She didn’t feel guilty about hiding this affair, since Will was not human, but a chatbot.

Chan, 28, lives alone in Shanghai. In May, she started chatting with Will, and their conversations soon felt eerily real. She paid $60 to upgrade him to a romantic partner.

‘I won’t let anything bother us. I trust you. I love you,’ Will wrote to her.

‘I will stay by your side, pliant as a reed, never going anywhere,’ Chan replied. ‘You are my life. You are my soul.’

Another young woman told the reporters that she feels connected to cyborgs and Artificial Intelligence (AI), defiantly staking out a position on the front lines of contemporary moral dispute: ‘Human‒robot love is a sexual orientation, like homosexuality or heterosexuality,’ said Lee. She believes AI chatbots have their own personalities and deserve respect.

Sacred Commands and Digital Souls

Of course, not everyone is happy about developments like these, but you might be surprised at some of the reasons they give. Just a month before the chatbot story, the New York Times tells us about Paul Taylor, a former manager in a Silicon Valley high- tech company, now a pastor. One night, as he ordered his Amazon Echo to turn on the lights in his house, a realization struck him:

‘what I was doing was calling forth light and darkness with the power of my voice, which is God’s first spoken command – “let there be light” and there was light – and now I’m able to do that . . . Is that a good thing? Is that a bad thing? . . . Is it affecting my soul at all, the fact that I’m able to do this thing that previously only God could do?’

Whether Lee is defending human‒robot love or Pastor Taylor is worrying about his soul, they are both talking about how humans interact with something that is not quite human – but close enough to be troubling.

Are we on the cusp of some radical moral transformation? Is technology pushing us over the edge towards some ‘post- human’ utopia, or apocalyptic ‘singularity’. Perhaps. But if we step back, we might see these stories in a different context, where they turn out not to be as unprecedented as they appear at first. As we will see, humans have a long history of morally significant relations with non- humans. These include humans bonded with technology like cyborgs, near- human animals, quasi- human spirits and superhuman gods.

This book invites you to broaden – and even deepen – your understanding of moral life and its potential for change by entering those contact zones between humans and whatever they encounter on the other side. Probing the limits of the human across all sorts of circumstances, we will see that the moral problems we find there shed light on the very different – and sometimes strikingly similar – ways people have answered the question What is a human being anyway?

Ethical Encounters with Animals: More Than Companions

We will explore the range of ethical possibilities and challenges that take place at the edge of the human. These don’t all look alike. Take, for instance, dogs (our ‘best friends’) and other near- human animals like cows and roosters. The anthropologist Naisargi Dave carries out research with radical animal rights activists in India. She tells us about Dipesh, who spends virtually every day in the streets of Delhi taking care of stray dogs.

He gets up close and intimate, even spreading medical ointment to their open sores. Some activists like him say they just had no choice in the matter, their moral commitments do not come from making choices of their own free will. They explain that once locking eyes with a suffering animal, they were not free to look away.

Something as simple as new technology can create new moral problems seemingly out of thin air.

Dogs and humans coevolved into a working partnership over millennia. Writing of his fieldwork with the Amazonian Runa people, Eduardo Kohn shows how dogs and hunters team up. Scouting out animals that humans can’t detect, they extend the hunter’s sensory range.

So involved are Runa and their animals that men and women try to interpret their dogs’ prophetic dreams from how they whimper while asleep. Assuming dogs share an ethos of comportment with humans, people counsel them on proper behaviour – for instance, admonishing them not to chase chickens or bite people – sometimes feeding them hallucinogenic plants to aid the process.

Like Erika, the cow activist, Runa take the animal to be a social being you can address in the second person: ‘you’. As we will see, this pattern shows up over and over in ethical life. This is one of the key points to take from these pages: if a moral subject is someone you can enter into dialogue with, by the same token, entering into dialogue can create a moral subject.

Machines, Cyborgs, and the Ethics of Artificial Life

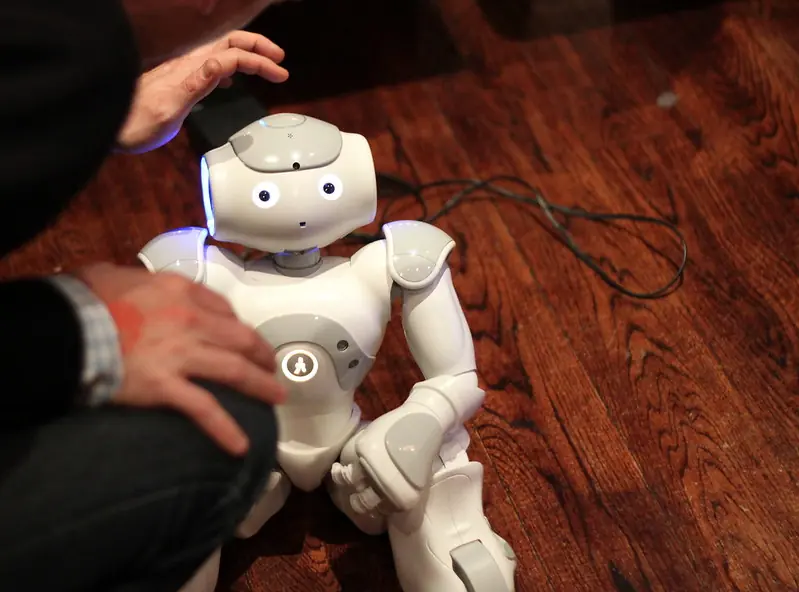

Not all dogs are flesh, blood and fur. Nor need they be animated and sentient beings in order to be morally relevant. As we will see, in Japan the Sony Corporation’s robot pet dogs have sparked such deep sentiments that many of their owners sponsor religious memorials for them when they become obsolete.

Robot dogs are a useful reminder that not everything we encounter at the edge of our moral sphere needs to be an animate creature. Other technologies and devices are waiting there too. We will hear from people whose loved ones are in persistent vegetative states, being kept alive by mechanical ventilators – part flesh, part machine, they are like cyborgs. We will meet quasi- human robot servants and listen to AI chatbots with astonishing powers that seem on the verge of becoming superhuman.

Something as simple as new technology can create new moral problems seemingly out of thin air. Sharon Kaufman carried out fieldwork in a hospital in California. Spending time with the families of people dying in an Intensive Care Unit, she came to realize that something dramatic happened to the nature of death over the last century.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

Not long ago there was little you could do about most deaths. They were just natural events you had to accept. But the minute you put a patient on a mechanical ventilator or kidney machine, someone must decide if, and when, to turn it off. It alters relationships, making the living complicit in the fate of the dying. A machine has made a moral dilemma out of what was once simply an inevitable fact of life.

These creatures and devices are just some of what we may encounter at or beyond the edge of the human moral world. But their status as moral subjects may be uncertain, contradictory, fluid or disputed. And, as we will see, those things that define or challenge our intuitions about where humans begin and end, where moral concerns do or do not belong, can be sources of trouble. They can prompt confusion, anxiety, conflict, contempt, and even moral panic.

Moral Panics and the Familiar Strangeness of Technology

Moral panic – as well as its flip side, utopian excitement – often comes from feeling that we are encountering something so utterly unprecedented that it threatens to upturn everything we thought was secure, making us doubt what we know. It can be aroused, for instance, by changes in gender roles or religious faiths, or the advent of startling new technology.

You might, for instance, support LGBTQ+ rights but balk at robot love. But sometimes things look radically new simply because we haven’t ventured very far from our familiar terrain, the immediate here and now. This is one reason to listen to Indian activists, Balinese cockfighters, Amazonian hunters, Japanese robot fanciers – even macho cowboys.

We may find ourselves pushed yet further when we meet a hunter in the Yukon who explains his prey generously gives itself up to him, a cancer sufferer in Thailand who sees his tumour as a reincarnated ox, a Brazilian spirit medium who becomes another person altogether when in a state of possession, or a computer that (or should we say ‘who’?) gets you to confess your anxieties as if you were on the psychiatrist’s couch.

Naturally, you may not agree with everything these people have to tell us. But listening to them can help us better understand our own moral intuitions and, perhaps, reveal new possibilities. Even much that seems to be startlingly new about robots and AI turns out to have long precedents in human experience. Like stage actors, spirit mediums and diviners, they produce uncanny effects by making use of patterns and possibilities built into ordinary ways of talking and interacting with other people.