Shortly after the recent election, the New York Times reported the results of a new study documenting a deep and pervasive pessimism among the American public, cutting across ideological lines. Only a quarter of Americans think the country’s best days are ahead, only one in ten thinks the government represents them well. This is broadly true both of Trump supporters and of the half of the country that voted against him. “In a sense,” the report concludes, “it is in the deep chords of distrust where Americans seem most united.”

Serge Schmemann, the Times editorial board member who wrote about the study, lamented that it “left unanswered the wrenching question that we must answer if things are to improve: Why? Why has America fallen into the deep malaise quantified by this study? Why are we so down on our country, our government, our prospects? Why is there so much hatred in our civil discourse?”

It’s hard to think of an area of domestic policy other than criminal justice where American democracy has failed as spectacularly over the past several decades, or with worse consequences.

I offer a partial answer in my new book, Criminal Justice in Divided America: Police, Punishment, and the Future of Our Democracy. Failures of the criminal legal system helped to drive American politics toward populism, polarization, and pessimism. By the same token, the right kinds of reforms can not only make policing, prosecution, and punishment fairer and more effective; they can assist in rebuilding American democracy.

Crime Politics from Goldwater to Trump

It’s hard to think of an area of domestic policy other than criminal justice where American democracy has failed as spectacularly over the past several decades, or with worse consequences. It is hard to be upbeat about the country when you lack confidence that government’s bluntest tools—the police and prisons—will be used fairly and in a way that keeps you safe.

When the Republic party began its long journey toward right-wing populism in the late 1960s, no issue fueled conservative discontent more than the failure of government to provide “law and order.” The politics of crime were the heart of Barry Goldwater’s unsuccessful campaign for president in 1964, and they helped fuel the later victories of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan. By the 1980s, Democrats were competing with Republicans to propose the harshest anti-crime policies, and the eventual results were the disasters of mass incarceration and hypermilitarized policing.

The politics of crime have always been, in part, a way of talking about race.

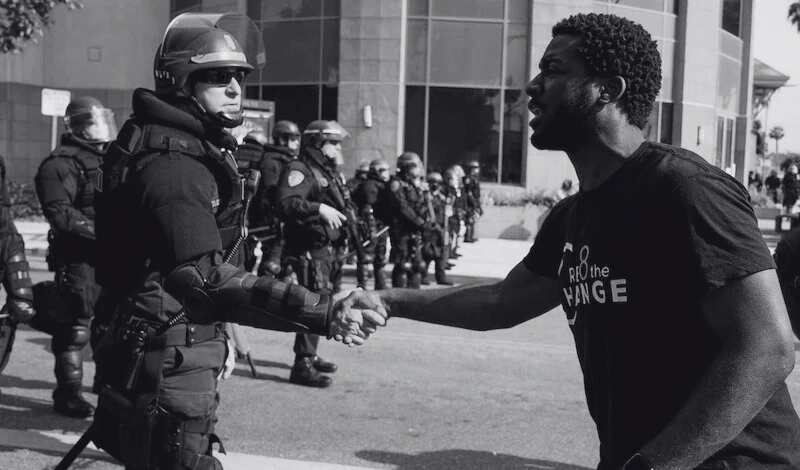

Those developments, in turn, led in the summer of 2020—during a pandemic, no less—to the most widespread protests and civic disturbances the country had seen in decades. They led, as well, to the wholesale discrediting of what had been an extraordinarily promising program of police reform—the community policing movement. Bridges that had taken a quarter-century to build between police departments and minority neighborhoods suddenly collapsed.

The level of trust in law enforcement reached historic lows from which it is just beginning to recover. At the same time, attacks on the police have felt to many Americans like reckless attacks on safety and morality. Voters angered by crime and public disorder have ousted “progressive prosecutors” seen as too lenient or too anti-police, often a few short years after those very prosecutors were elected precisely because they had promised less sever sentences and more scrutiny of law enforcement.

The politics of crime have always been, in part, a way of talking about race. But crime rates really did skyrocket in the 1960s and early 1970s, and fear of crime spanned racial divides—just as it does today. This is one reason the GOP, and Trump in particular, gained significant support among Black Americans and Latinos between his first election as president in 2016 and his second in 2024.

In the runup to the 2024 presidential race, Republican voters told pollsters they cared more about “law and order” than about battling “wokeness.” And even in California, where Latinos outnumber whites and the Democratic Party has a virtual lock on statewide elected offices, voters in 2024 approved an initiative raising criminal sentences for theft and drug possession, rejected a state constitutional amendment banning forced labor in prisons, and recalled two “progressive prosecutors,” one in deep blue Los Angeles, and a second in deeper blue Alameda County.

The Poison of Abusive Policing

Crime rates are influenced by many things beyond law enforcement. In fact, the conventional wisdom among scholars and even many police executives by the late twentieth century was that law enforcement was not an influence at all; neither varying the number of officers nor changing their policing strategies and tactics seemed to have any effect on crime rates.

![Detroit police officers clash with African-American residents during the 1967 riots, a pivotal moment in the city's history of racial tension and criminal justice disparities. [Photo: Lee Balterman]](https://politicsrights.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Criminal-justice-in-the-1960.webp)

But there’s good evidence now that crime can reduced by the right kind of policing—policing that relies on extensive consultation and trust-building with a broad cross-section of the public. This is pretty much the opposite of the kind of “professional” policing that had become standard in the United States by the 1960s and 1970s.

Much of the impetus for the riots of the 1960s and 1970s came from the policies and practices of criminal justice institutions.

Obviously, bad policing can’t take all the blame for the high crime rates of the late 1960s and the 1970s, let alone for the rightward shift of the Republican Party, the eventual rise of divisive forms of populism in the United States, or the extreme polarization that now plagues our politics. But it contributed to all of these problems, and not just by its ineffectiveness.

The biggest problem with the police in the 1960s and the 1970s wasn’t their failure to keep crime down, it was their abusive and frequently brutal treatment of African Americans, members of other racial minorities, and political protesters. The widespread urban riots of the 1960s and 1970s were almost all triggered by a confrontation between officers and a Black motorist, a Black suspect, or a Black crowd. And very often it was a confrontation involving police violence.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

But it wasn’t just policing that sparked the riots of the 1960s and 1970s. It was the criminal legal system as a whole: abusive policing; plus the failure of law enforcement agencies, prosecutors, and courts to hold the offending officers accountable; plus the legal system’s broader failure to act, as a later generation of activists would put it, as though Black lives mattered.

Much of the impetus for the riots of the 1960s and 1970s thus came from the policies and practices of criminal justice institutions: the police in particular, but also prosecutors, judges, and juries. And it is hard to overstate the political consequences of the riots of the 1960s and 1970s, in the short term and over the succeeding decades. More than any other events, it may have been the riots that galvanized conservative politics in the 1960s and allowed crime and policing to become the leading domestic issue as the decade drew to a close.

The Spiral of Fear

Crime, riots, and the politics of law and order in the 1960s and 1970s did not just jumpstart the modern conservative movement; they also drove the adoption of punitive policies that themselves, over the long term, helped to split the country apart and lay the groundwork for the rise of right-wing populism.

Ironically, much of the legislation responsible for the militarization of policing and the explosive growth of prison populations in the closing decades of the twentieth century was proposed not by Republicans but by Democrats, who were determined not to be seen as soft on crime. But although longer sentences and more aggressive policing were supposed to allow Americans to live less fearfully, they had the opposite effect, partly because for most part they did not reduce crime, and partly because the new policies, and the rhetoric surrounding their adoption, changed how Americans thought about risk, safety, and the role of government.

We need to replace a commitment to popular sovereignty with a commitment to democratic pluralism.

The war on crime helped to inculcate a new, heightened concern for safety, a pervasive fear of victimization, and the view that a central job of government was to keep good people separated from and protected against bad people.

The sociologist David Garland has called this the “culture of control.” When Donald Trump launched his long-shot presidential campaign in 2016 by railing against the “rapists” and drug dealers he said were coming into the United States illegally, when he anchored his campaign on a promise to build a “big, beautiful wall” all along the Mexican border, when he called himself “the law and order candidate” and later “your president of law and order,” he was presenting himself as the apotheosis of the culture of control, and a direct if delayed product of the crime politics of the 1960s and 1970s.

The venomous polarization in the United States today and the continuing threat of authoritarian populism can’t be blamed just on the politics of crime over the past half century, or on the failures and pathologies of policing, prosecution, and punishment. But it is difficult to identify any other set of issues that contributed so strongly and continuously to the rightward shift of the Republican Party in the closing decades of the twentieth century, the subsequent rise of Trump and his MAGA movement, and the division and enmity that have to come to characterize our national discourse.

For criminal justice reforms to succeed they need to take seriously the complexity of American society.

Policing, prosecution, and punishment didn’t break American democracy all by themselves, but they did a lot of the damage, first by failing to provide adequate protection against crime and abusive policing, and then by doubling down on severity for the sake of severity.

There was one bright spot in criminal justice policies in the 1980s and 1990s. New approaches to law enforcement, generally grouped together under the label “community policing,” reoriented officers away from a warrior mentality and toward a guardian mentality, and encouraged them to work with their local communities and respond to their concerns. Unlike the draconian prison sentences adopted in this era, and unlike the militarized tactics and equipment that police departments often adopted at the same time they were pursuing community policing, community policing really did help to reduce crime and the fear of crime.

But community policing was critically undermined by a naïve assumption that the “community” could be trusted to speak with one voice, and consulting with the community too often meant consulting just with business owners, property owners, and older residents. One consequence was that community policing programs rarely addressed the problem of police violence, which was disproportionately experienced by young people. And the tragic blindness to police violence is a large part of why community policing eventually lost most of its support among leftwing activists.

Police and Punishment in a Divided Country

There is an important lesson here. For criminal justice reforms to succeed—especially in a country as polarized as the United States today—they need to take seriously the complexity of American society. They can’t rely on the idea of a unified “community”—or, at the national level, a unified “people.” That means that in thinking about the connections between criminal justice and democracy, we can’t understand democracy as a matter of putting the “people” or the “community” in charge.

There’s another reason to reject that understanding of democracy: it is ill-suited to our current political moment. The rise of polarization has made the myth of a unified “people” look increasingly threadbare, and the dangers of that myth have been underscored by the rise of forms of populism that emphasize the protection of “true” Americans against outsiders and elites.

We need to replace a commitment to popular sovereignty with a commitment to democratic pluralism—the idea that democracy is at bottom a set of procedures for allowing people with conflicting views and commitments to make collective decisions in a fair and peaceful manner, leaving space for dissenters.

Here is some of what that means.

First, to make the criminal legal system safe for democracy—to prevent it from endangering democracy as it has over the past half-century—we need to make it more effective, but also fairer and more humane. This means, for example, recommitting to the agenda of community-based policing, but without the narrow, naïve conception of “community” that limited the ambitions of those programs and blinded them, far too often, to the scale of police violence and the toxicity of police racism.

Second, because processes are at the heart of democratic pluralism, the processes of criminal justice—including criminal trials, sentencing hearings, and procedures governing probation, parole, and clemency—should be assessed by asking whether they help to advance, or instead undermine, democratic pluralism’s twin goals of political equality and social peace. This means, for example, taking greater advantage of the ability of criminal juries to develop habits and skills of democratic citizenship, in part by making jury pools more representative, and by increasing the number of jury trials by cutting back on plea bargaining.

It also means attending to the toll that mass incarceration takes on social equality and social peace, and therefore on the prospects for democracy in a diverse society. Similarly, the health of American democracy also requires reducing the crushing burdens that non-carceral sanctions—financial penalties and civil disabilities—can impose on people convicted of crimes, burdens that often keep them permanently exiled from full civic participation, and trap them in an escalating cycle of sanctions for failure to pay earlier sanctions.

Third, we should want the criminal justice system to promote, or at least not to eat away at, the values that support democratic pluralism, including the rule of law and objective truth. We should also want the criminal legal system to help sustain, or at a minimum avoid undermining, the institutions that support these norms, such as independent courts and a responsible legal profession.

This means, among other things, rethinking the way the United States picks judges. It also means de-personalizing clemency: pardons and commutations should not be matters of presidential or gubernatorial whim. And it means addressing the excessive power of American prosecutors—something the “progressive prosecutor” movement has largely failed to do, but which the present political moment may allow us to pursue in ways that can draw support from across the ideological spectrum.

A better understanding of democracy can help us make policing, prosecution, and punishment more effective, more equitable, and more humane.

Fourth, promising reforms in criminal justice have often been abandoned before having had the chance to succeed, or even just as they were beginning to succeed. Particularly in times of deep social division, therefore, we should look for potential reforms which can garner support across lines of race, class, and ideology. Fortunately, the approaches to criminal justice reform must likely to succeed if given a chance—such as a revived and reinvigorated commitment to community policing, an expansion and strengthening of the jury system, reasonable restrictions on prosecutorial power, and efforts to avoid both excessive severity and excessive lenience in punishment—will often also be the ones for which it will be easiest to build political consensus.

The failures of American criminal justice are not the only reason for the poisonous condition of politics in the United States. But policing, prosecution, and punishment played a large role in creating those politics. So rebuilding American democracy will require new approaches to criminal justice. And it works the other way, too.

We can’t solve the crisis of criminal justice without taking account of the crisis of American democracy. A better understanding of democracy—one rooted in democratic pluralism rather than the myth of the “people”—can help us make policing, prosecution, and punishment more effective, more equitable, and more humane. And those reforms, in turn, can help us make American society more truly and resiliently democratic.