Illiberalism is defined by both its opposition to and dependence on liberalism—understood as an ideology and as a democratic system. Its meaning remains contested, partly due to the inherent ambiguity of liberalism itself. Kauth and King distinguish between ideological illiberalism, which seeks to restrict group rights, and disruptive illiberalism, which challenges democratic procedures. These forms converge around two key traits: an exclusionary ideology and rejection of liberal pluralism.

- Illiberalism’s Core Logic: Collective Identity and Institutional Tensions

- Conceptual Struggles: Framing Illiberalism in Political Discourse

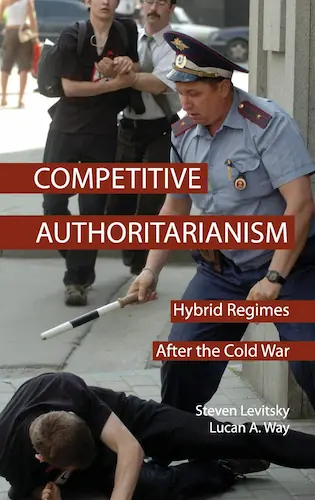

- Competitive Authoritarianism: Institutional Manipulation in Semi-Free Systems

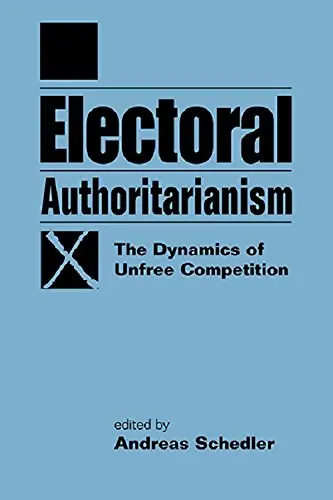

- Electoral Authoritarianism: Power Retention Behind a Democratic Façade

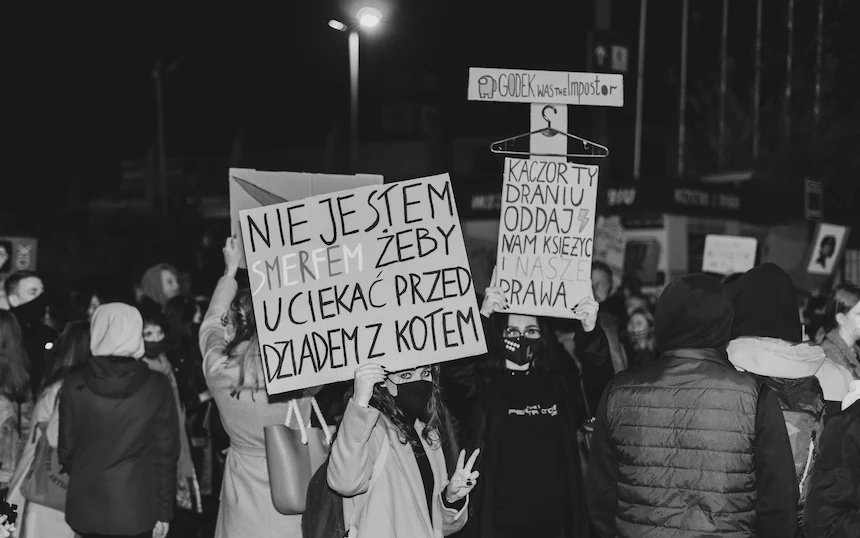

- Autocratic Legalism: Institutionalising Authoritarian Power

- Democratic Backsliding: Incremental Routes to Institutional Decline

- The Ideological Engine: What Drives Hybrid Regime Dynamics

- Recognising the Stakes: Illiberalism as a Coherent Political Force

- Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

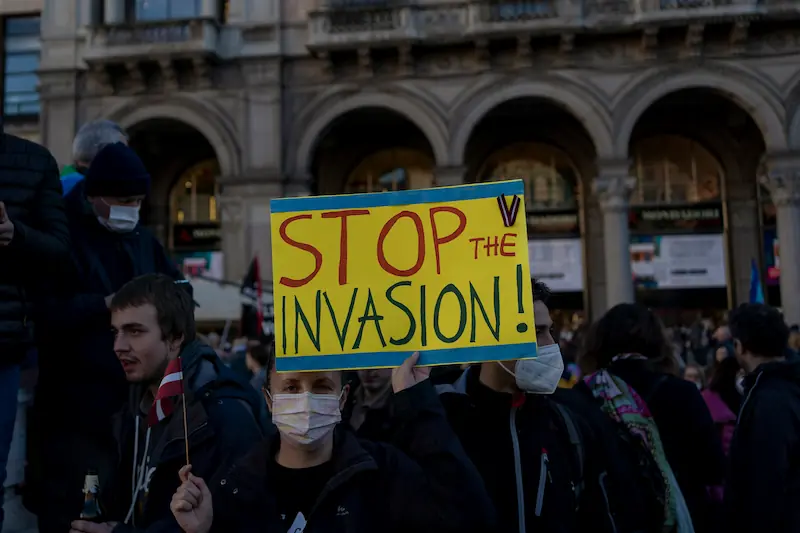

- Global Footprint: Mapping Illiberal Practices and Narratives

With Pablo Baez Guersi (Moncada and Baez Guersi, in review), we build on this definition. First, illiberal discourse elevates the collective over the individual, framing society as a binary: a homogeneous national majority versus a minority cast as culturally, demographically, economically, or security-threatening.

In light of recent efforts to harmonise definitions of illiberalism, it is no longer tenable to claim that the concept is vague or analytically useless in understanding the contemporary world.

Second, illiberalism sustains a paradoxical relationship with liberal democracy—condemning liberal institutions for empowering minorities, while invoking their defence to justify exclusionary policies, arguing that minorities themselves are hostile to liberal values and institutions.

Illiberalism’s Core Logic: Collective Identity and Institutional Tensions

In his doctoral thesis, Demias Morisset offers a more nuanced conceptualisation of illiberalism, distilled into five core components: the nation, religion, the family, decisionism, and the market. Among these, the first three are, in his view, the most consistently present across illiberal discourses. The nation is framed in nativist and xenophobic terms, as a culturally and ethnically homogeneous entity.

This national narrative is reinforced by anti-individualist rhetoric, privileging the collective over individual rights, and by a dualistic conception of the state, which allocates distinct rights to nationals and non-nationals. These principles manifest in anti-immigration laws, the rejection of international agreements, resistance to supranational court rulings, and restrictions on human rights NGOs.

Religion is positioned in opposition to both universalist rationalism and secularism, understood as the strict separation of church and state. It advocates for the integration of spiritual values into public and private life and sustains a patriarchal vision of the family as the antithesis of liberal individualism.

In this framework, the family is defined by heterosexual marriage, gender binarism, and intrafamilial solidarity, and is mobilised against feminism, gender theory, and the welfare state. This justifies restrictive policies on divorce, abortion, homosexuality, non-reproductive sexuality, and the visibility of LGBTQ+ identities in the public sphere.

The concept of decisionism, drawn from Carl Schmitt, centres on strong, centralised executive power, exercised by a sovereign figure capable of declaring exceptions and acting beyond abstract legal norms. This challenges liberal constitutionalism and the separation of powers, and, as Demias Morisset argues, often contributes to the blurring of illiberalism with authoritarianism.

Finally, the market holds an ambivalent place. It may serve the illiberal agenda through neoliberal, anti-interventionist policies, or as an instrument of national sovereignty through protectionism. In both cases, it underwrites a rejection of redistributive welfare measures and supports fiscal advantages for corporations and economic elites.

Conceptual Struggles: Framing Illiberalism in Political Discourse

Decisionism has arguably prompted one of the most significant critiques of illiberalism. Many scholars contend that the term “illiberal democracy” is inherently contradictory: describing such regimes as democratic confers undue legitimacy on systems that systematically erode democratic principles.

One body of research therefore favours the term authoritarianism to capture these transformations, drawing on frameworks such as competitive authoritarianism, electoral authoritarianism, and autocratic legalism.

By contrast, a second strand of scholarship retains the language of democracy to emphasise the gradual erosion of democratic norms, as encapsulated in concepts like democratic backsliding. Scholars of hybrid regimes within this tradition generally argue that liberal democracy is experiencing a global regression worldwide, even as strictly authoritarian models are also receding.

Competitive Authoritarianism: Institutional Manipulation in Semi-Free Systems

In competitive authoritarian regimes, formal democratic institutions exist, and elections are regularly held and generally free from overt fraud.

However, incumbents routinely violate democratic norms, preventing these systems from meeting the minimum standards of democracy.

While not fully autocratic, such regimes exploit state resources, media control, legal harassment, and selective repression to weaken the opposition.

Unlike other hybrid regimes, competitive authoritarianism is defined by genuine but systematically unfair competition.

Examples include Croatia under Franjo Tuđman, Serbia under Slobodan Milošević, Russia under Vladimir Putin (pre-2012), Ukraine under Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma, Peru under Alberto Fujimori, post-1995 Haiti, and Albania, Armenia, Ghana, Kenya, Malaysia, Mexico, and Zambia during the 1990s.

In these contexts, the opposition retains the capacity to challenge incumbents—and occasionally even win elections.

Electoral Authoritarianism: Power Retention Behind a Democratic Façade

Electoral authoritarianism describes regimes where multiparty elections occur regularly, but are structurally biased and lack real competitiveness.

Opposition parties and institutions exist in form, but incumbents manipulate media, undermine judicial independence, and exploit state resources to retain power.

These regimes maintain a democratic façade while exercising authoritarian control, using elections and fraud as instruments of domination rather than accountability.

In some cases—such as Nursultan Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan, Alyaksandr Lukashenka in Belarus, Ilham Aliyev in Azerbaijan, and Russia under Vladimir Putin (post-2012)—this model has evolved into hegemonic personalist regimes.

These are more deeply authoritarian than competitive authoritarian regimes: elections are symbolic, with marginalised opposition and no genuine prospect of power transfer.

Autocratic Legalism: Institutionalising Authoritarian Power

Autocratic legalism refers to a mode of governance in which elected leaders use legal and constitutional tools to entrench authoritarian power. Legal autocrats win elections and then manipulate laws to weaken opposition, control the media, and rewrite constitutions, turning previously unconstitutional practices into legal norms.

This strategy preserves a veneer of democratic legitimacy while eroding checks on executive authority. Once public support declines, the legal system has already been rigged, rendering democracy hollow and eliminating meaningful avenues for citizens to challenge power. In Hungary, Viktor Orbán’s government rewrote the Constitution in 2011 after securing a two-thirds majority, allowing the adoption of cardinal laws to entrench Fidesz’s agenda.

Judicial reforms included lowering the retirement age to replace senior judges with loyalists and creating a party-controlled National Judicial Office, centralising authority and undermining judicial independence.

In Poland, the Law and Justice Party (PiS) implemented similar changes—lowering the retirement age of Supreme Court judges, weakening the Constitutional Tribunal and the National Council of the Judiciary—to consolidate executive control. Autocratic legalism is not a regime type, but a process by which a regime becomes less democratic. It can emerge within competitive authoritarianism and evolve into electoral authoritarianism.

Democratic Backsliding: Incremental Routes to Institutional Decline

Democratic backsliding is a shift from dramatic regime breakdowns to the gradual, legal, and often subtle erosion of democratic institutions.

Instead of military coups or blatant electoral fraud, backsliding today typically occurs through promissory coups, executive aggrandisement, and strategic electoral manipulation. In promissory coups, actors justify the ousting of elected leaders as a temporary measure to restore democracy—though such promises are rarely fulfilled.

Illiberalism constitutes a structured, coherent, and dangerous ideology.

For example, Honduras (2009) saw the removal of President Manuel Zelaya, followed by elections favouring the coup coalition.

Similar patterns emerged in Fiji (2006) under Frank Bainimarama, who ruled by decree until 2014; Gambia (1994, Yahya Jammeh); Pakistan (1999, Pervez Musharraf); Madagascar (2009, Andry Rajoelina); and Haiti (1991, Jean-Bertrand Aristide), where formal electoral returns masked democratic decline.

Executive aggrandisement, a more widespread form, involves legally expanding executive power and weakening institutional checks. Leaders like Recep Tayyip Erdoğan (Turkey), Rafael Correa (Ecuador), Abdoulaye Wade (Senegal), and Viktor Yanukovych (Ukraine) used constitutional reforms, judicial restructuring, and media control to entrench power while maintaining a democratic façade. This form is closely related to autocratic legalism.

A third mechanism, strategic electoral manipulation, subtly tilts the playing field in favour of incumbents—through legal adjustments to media regulations, candidate restrictions, and state resource misuse—without overt fraud. These practices are central to how regimes become or operate as competitive authoritarian systems. In Turkey and Ecuador, such strategies reinforced executive aggrandisement, sustaining electoral legitimacy while eroding genuine competition.

The Ideological Engine: What Drives Hybrid Regime Dynamics

We observe notable overlaps between these concepts: autocratic legalism may evolve into competitive or electoral authoritarianism; executive aggrandisement and autocratic legalism are closely related; and strategic electoral manipulation mirrors features of competitive authoritarianism.

Some terms are synchronic or cross-sectional, identifying a continuum that classifies hybrid regimes along a spectrum of authoritarianism (e.g. competitive vs. electoral authoritarianism). Others are diachronic or longitudinal, emphasising a process of autocratic consolidation (autocratic legalism) or democratic decline (democratic backsliding). Despite these differences, these concepts are often used interchangeably.

Illiberalism is a key concept for understanding ongoing transformations in both democratic and authoritarian regimes.

Crucially, by focusing solely on regime type, these four concepts tend to neglect ideology, which may in fact be the driving force behind their hybrid nature. The hybrid regime framed by illiberalism is deliberately vague, allowing it to span a broad range from competitive to electoral authoritarianism. Illiberalism is conceived both as a regime type, observable at a particular moment, and as a process of hybridisation.

Its key contribution lies in its ability to articulate a “thick” ideology, borrowing from debates on populism. A thick ideology refers to a broad, coherent belief system that offers a comprehensive moral and political vision of society. It includes core beliefs about justice, power, human nature, and governance, shaping both political behaviour and public policy.

Recognising the Stakes: Illiberalism as a Coherent Political Force

Illiberalism is a key concept for understanding ongoing transformations in both democratic and authoritarian regimes. A recent study has developed a method to measure the extent of illiberal ideology in around sixty European political parties, based on their explicit positions on gender and immigration.

More broadly, the repeated targeting of specific groups—including women, LGBT+ individuals, ethnic and religious minorities, people with immigrant backgrounds, persons with disabilities, working-class communities, journalists, NGOs, and intellectuals—is best understood in relation to an underlying nativist and patriarchal ideology. This worldview opposes secularism and the welfare state, while promoting a strong state and an economic model that privileges corporate and elite interests.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

In light of recent efforts to harmonise definitions of illiberalism, it is no longer tenable to claim that the concept is vague or analytically useless in understanding the contemporary world. Illiberalism constitutes a structured, coherent, and dangerous ideology. While it may be more accurate to associate it with a regime type rather than democracy itself, dismissing it as a mere euphemism for autocracy is misleading.

An illiberal regime is a hybrid form—which may appear as competitive or electoral authoritarianism, and may evolve through processes such as autocratic legalism or democratic backsliding. Crucially, a regime is considered illiberal only when it draws upon all or part of the five ideological pillars identified by Demias Morisset : the nation, religion, the family, decisionism, and the market.

Global Footprint: Mapping Illiberal Practices and Narratives

Building on the work of Schafer, Wagner, and Yavuz (2025) on political parties, it is important to extend the identification of illiberal thought beyond executive branches, exploring its presence in public administrations and private entities. Academic research has examined the diffusion of illiberal ideas in European media, as well as in non-European contexts. However, some countries—notably France—remain understudied in this regard.

Conversely, to better understand the practices and discourses of illiberal regimes, it would be useful to shift attention to countries beyond those already extensively examined such as Hungary and Poland. Other relevant cases include Romania, Russia, Israel, China, India, Singapore and the Philippines as well as several countries in the Global South, and the United States. For instance, Africa and South America remain underexplored continents.