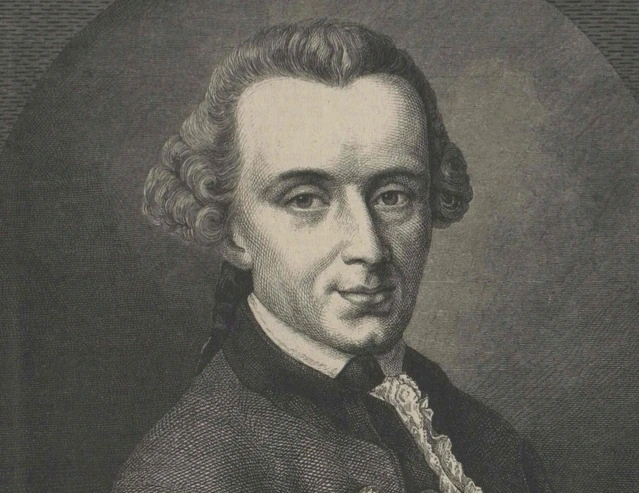

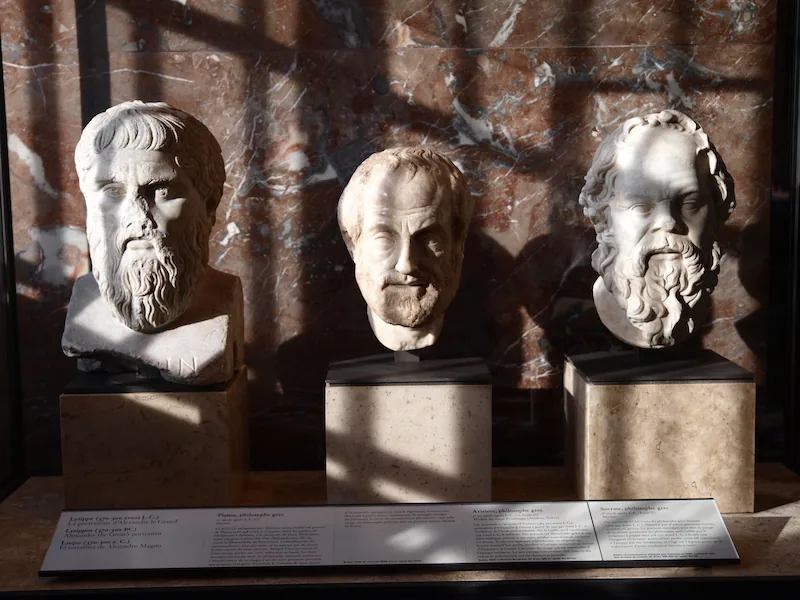

My book introduces contemporary philosophical work on moral judgment originating from France, Germany, and the Anglo-American world. It focuses on thinkers significantly influenced by Kant or Aristotle, with a primary historiographical objective. Specifically, I aim to show that contemporary Kantianism has been profoundly transformed by what I refer to as the neo-Aristotelian critique of Kantian judgment.

Even if we admit that practical identities are a source of reasons for action, this itself does not entail that we cannot rationally prioritize one dimension of our identity over all others.

Additionally, I wanted to assist readers in familiarizing themselves with several French and German philosophical works that have not been extensively examined within Anglo-American philosophy. This includes contributions from Sartre, Merleau-Ponty, Arendt, Rüdiger Bubner, Jürgen Habermas, Vincent Descombes, Alain Renaut, and Souleymane Bachir Diagne, which I put in dialogue with Anglo-American philosophers such as Christine Korsgaard, Barbara Herman, Onora O’Neill, Nancy Sherman, Alastair MacIntyre, Philippa Foot and John McDowell.

The Neo-Aristotelian Critique of Kantian Judgement

The neo-Aristotelian critique of Kantian judgment is based on the belief that moral judgment cannot be accurately described as the application of general principles to specific cases. One of the central claims of Moral Judgment is that this critique parallelly developed in France, Germany, and the Anglo-American world during the 20th and 21st centuries.

In the book’s first part, I divide the neo-Aristotelian critique into three main objections. The first objection states that the moral principles defended by Kantian philosophers are essentially foundationless.

Although they may seem universal or objective, these principles merely reflect the contingent moral views of a historically and geographically situated community. Accordingly, there is no such thing as a standpoint of humanity or pure reason.

The second objection claims that moral principles are too general to guide action effectively. Moral agents can respect these principles in myriad ways, but the difficult task of moral judgment amounts to identifying the best way to do so.

Lastly, the third objection builds on the second: to determine the best course of action, agents cannot solely rely on principles but must acquire moral and intellectual virtues.

In the book’s second part, I turn my attention to various Kantian responses to the first objection. Specifically, I examine recent attempts to provide a foundation for moral principles by engaging with the work of Christine Korsgaard, Jürgen Habermas, Alain Renaut, Philippa Foot, and John McDowell.

Finally, in the book’s third part, I argue that many contemporary Kantians, such as Hannah Arendt, Nancy Sherman, Barbara Herman, and Onora O’Neill, agree that moral judgment involves an element of skill and that general principles alone cannot guide action.

A Teleological Conception of Practical Identities

For reasons of space, I cannot assess the strength of all the abovementioned objections and responses here. Instead, I propose to discuss a philosophical problem at the core of Moral Judgement to illustrate the methodology I use in my book.

The starting point of this discussion is an essay by French Aristotelian Vincent Descombes titled “Philosophie du jugement politique” (1994). In this essay, Descombes attempts to ground moral judgment in a teleological conception of practical identities, a concept which refers to our social roles (in my case, for instance, father, spouse, friend, and philosophy professor).

Like other contemporary Aristotelians, Descombes suggests that practical ends are intrinsically connected to these identities. For example, we can say that “teaching well” is an end that belongs to my identity as a philosophy professor, as it generally befits professors to teach effectively.

Descombes essentially portrays moral judgment as the task of identifying the means that best allow us to achieve the ends associated with our practical identities. His remarks echo Nicomachean Ethics 1112b (1984), where Aristotle contends that we do not deliberate about ends but about means.

As Aristotle notes, doctors do not deliberate about whether they should cure, orators about whether they should convince, or legislators about whether they should make good laws. Like it befits a professor to teach well, it befits a doctor to cure patients or a legislator to make good laws. In all those cases, not pursuing these ends would amount to an error in judgment.

As reflective beings, we are endowed with the capacity to question the value of any dimension of our identity.

Famously, however, Elizabeth Anscombe identified a problem with the conception of moral judgment proposed by Descombes. Simply put, some practical identities are tied to immoral ends. Forcefully illustrating this point, Anscombe writes in Intention (1957), “It befits a Nazi, if he must die, to spend his last hour exterminating Jews.”

Here, Anscombe’s point is not that said Nazi ought to act in this way all things considered, but precisely the opposite. In other words, she offers a reductio of the teleological conception of practical identities discussed above. In the same sense as good doctors seek to cure their patients, “good” Nazis seek to perform horrible actions. But if the teleological conception of moral judgment forces us to condone horrible actions, it should be rejected.

Descombes is fully aware of Anscombe’s objection and seeks to refute it. In his view, our practical identity is multidimensional. If this is the case, then the ends belonging to the multiple dimensions of our identities may conflict. For example, imagine that Anscombe’s Nazi is not only a member of the NSDAP but also the rector of a research university. Arguably, it befits rectors to pursue certain ends, such as promoting science, truth and research.

Is there a way to determine which dimension of my identity should take priority?

According to Descombes, what it befits members of the NSDAP to do – such as showing unconditional deference to the Leader – is likely to conflict with the ends it befits a rector to pursue. For example, it might be impossible to show unconditional deference to the Leader while promoting science, truth and research, especially if he uses pseudoscience to justify his political objectives.

In other words, Descombes hopes that practical identities tied to immoral ends will eventually conflict with those tied to good ends. When this is so, moral agents will either have to abandon some dimensions of their practical identities or act irrationally by engaging in what he dubs monomaniacal reasoning. Monomaniacal reasoners are those that impose ends on practical identities to which they do not belong.

Imagine, for instance, that the Nazi rector argues that it befits rectors to show unconditional deference to the Leader regardless of how this impacts science, truth and research. Here, the rector makes a moral mistake by conflating the ends that belong to the practical identities “rector” and “member of the NSDAP.”

The Problem of Reflexivity

In Moral Judgement, I contend that Descombes’s solution is flawed. The problem is that we can easily picture a Nazi rector who knows very well that he is a lousy rector, but reflectively decides to prioritize his identity qua member of the NSDAP. Differently put, Descombes’s argument does not entail that this sort of reflective endorsement qualifies as a failure of moral judgment or rationality.

Even if we admit that practical identities are a source of reasons for action, this itself does not entail that we cannot rationally prioritize one dimension of our identity over all others. This is what I call the problem of reflexivity.

In my view, this problem not only haunts neo-Aristotelians like Descombes but also Kantian constructivists. To see this, consider a central claim by Christine Korsgaard in her seminal book The Sources of Normativity (1996). There, Korsgaard endorses the neo-Aristotelian claim that ends intrinsically belong to practical identities. As she writes, constructivists should begin “by accepting something like the communitarian’s point. It is necessary to have some conception of your practical identity, for without it you cannot have reasons to act” (120).

That said, Korsgaard quickly points out that this is not the final step in the philosophical reflection on the foundations of moral judgment. In her view, our practical identities only provide us with reasons for action if we assign value to them. As reflective beings, we are endowed with the capacity to question the value of any dimension of our identity.

Say I assign value to my identity as a professor. This provides me with a reason to strive to teach well. But why should I assign value to this dimension of my identity? Why should I consider it a source of reasons? And what should I do when the ends tied to the multiple dimensions of my identity conflict?

In certain situations, it will be impossible for a moral agent to simultaneously pursue the ends tied to all dimensions of their identity. For instance, being a good father or spouse sometimes requires me to be a worse professor. In fact, this is a good description of the situation I am in right now, writing this essay on a Saturday afternoon while my daughter is asking me if we can go to the playground. When this happens, should I choose to be a good father or a good professor? Is there a way to determine which dimension of my identity should take priority?

Existentialism in French Metaethics

That moral agents must often choose what dimension(s) of their identity to prioritize is a thought at the heart of 20th-century French philosophy. Consider Sartre’s famous description of a café waiter in Being and Nothingness:

His movement is quick and forward, a little too precise, a little too rapid. He comes toward the patrons with a step a little too quick. He bends forward a little too eagerly; his voice, his eyes express an interest a little too solicitous for the order of the customer. Finally there he returns, trying to imitate in his walk the inflexible stiffness of some kind of automaton while carrying his tray with the recklessness of a tight-rope-walker by putting it in a perpetually unstable, perpetually broken equilibrium which he perpetually re-establishes by a light movement of the arm and hand.

All his behaviour seems to us a game. He applies himself to chaining his movements as if they were mechanisms, the one regulating the other; his gestures and even his voice seem to be mechanisms; he gives himself the quickness and pitiless rapidity of things. He is playing, he is amusing himself. But what is he playing? We need not watch long before we can explain it: he is playing at being a waiter in a café. (Sartre 1969, 59)

According to Sartre, the café waiter is an example of bad faith, which refers to willful oblivion. Another of stressing this point is to claim that the waiter wittingly forgets the problem of reflexivity. He acts as if he cannot be anything other than a café waiter. In reality, he freely decides to assign a value to his identity as a waiter and pursue the ends that come with it.

A café waiter has reasons to behave in specific ways. From an existentialist perspective, however, his choice to be a waiter is not itself motivated by reasons. It is a radically free, groundless decision, a purely spontaneous act of the will. And whatever he chooses to be, the waiter will always be free to stop being it. He can stop to reflectively endorse his identity qua waiter at any moment. When he does, this dimension of his identity will stop being a source of reasons for action.

Through the influence of Sartre, this idea made its way to French metaethics. For instance, we find a radicalized version of the problem of reflexivity in the works of Alain Renaut, an influential contemporary French Kantian philosopher.

According to Renaut, not only do we remain free to stop assigning value to specific dimensions of our practical identity, but the ends and reasons for action that flow from them are devoid of moral authority for us until we ratify them through an act of our will. As he writes in Débat sur l’éthique, “in order for the presence of reasons to lead me to act in one way over another, I must recognize them as good reasons. That is to say that I – and no one else in my place – must adhere to them, recognize myself in them.”

A Challenge for Kantian Constructivists

Kantian constructivists such as Korsgaard take a step further than Renaut by arguing that moral agents are not, in fact, radically free in the Sartrean sense. Indeed, there is one fundamental practical identity to which they must assign value: their identity as rational human agents. Here is a reconstruction of the argument that aims to support this conclusion:

- (1) To rationally value anything at all, I must have reasons to do so.

- (2) To have reasons to value anything at all, I must value a specific practical identity from which these reasons will spring.

- (3) To rationally value a specific practical identity, I must have reasons to do so.

- (4) To have reasons to value a specific practical identity rationally, I must value my identity qua rational human agent from which those reasons will spring.

There is, however, a significant problem with Karlgaard’s argument. Even if it is sound, it merely shows that I must necessarily value my identity qua rational human agent to value any other dimensions of my identity. Perhaps this fact makes such an identity more fundamental or necessary than others. But why should this fact lead me to assign greater value to it? Why should I consider that a more fundamental – or even a necessary – identity is more valuable than other dimensions of my identity? Can I not rationally do otherwise?

I believe I can. Here is an illustration. Imagine that Teresa, a paramedic, recognizes the value of humanity but is inclined to prioritize her obligations as a paramedic over her duty as a human being. By way of example, she often lies to individuals she assists qua paramedic by telling them that their injuries are not serious. This keeps them calmer, she finds, and facilitates her work.

If Kant was right about lying, Teresa does not fully respect the humanity of the individuals she assists, violating the second formula of Kant’s Categorical Imperative. Note, however, that her actions promote the well-being of the people it is her professional duty to help.

Is Teresa making a moral mistake? Possibly, but there remains a missing link between the outcome of Korsgaard’s transcendental argument—that is, the idea that humanity is necessarily valuable—and the claim that would allow us to establish that she did make such a mistake.

Indeed, the conclusion that I must attribute value to my identity qua rational human agent does not entail that I must also believe that it is the most valuable of all identities and that the obligations that spring from it systematically trump the obligations tied to my contingent practical identities.

In my view, the concept of practical identity is key to weaving Anglo-American, French, and German moral theories together.

If so, then I can rationally prioritize my obligations as a father, professor, or friend over those that directly stem from my identity as a rational human agent. Perhaps I can show unfair partiality to my daughter, for instance. This is not to say that this is how I ought to behave all things considered, but my point is that Korsgaard’s argument leaves this question open.

In many cases, I do believe I should prioritize my duties as a father. Right now, I should stop writing and take my daughter to the playground. But Sartre has a point: this all ultimately feels like a choice. Using philosophical resources, I am not convinced I could ground this choice in the way (some) Kantians would like me to. Unfortunately, I do not have a solution to offer to the problem of reflexivity.

In Moral Judgement, I simply wanted to raise this problem and show that neo-Aristotelianism, Sartrean existentialism, and Kantian constructivism are different ways of thinking about it. In my view, the concept of practical identity is key to weaving Anglo-American, French, and German moral theories together.

Admittedly, I have said nothing of German philosophy in this essay. I prefer to let readers turn to Moral Judgement to see how a version of the problem of reflexivity also haunts Habermas’s discourse ethics. Right now, however, my daughter is calling me. We must make it to the playground before sunset.