In the book “L’Etat numérique et les droits humains ,” professor and researcher Elise Degrave explores, drawing from cases she has personally experienced, the challenges to be addressed and the practical solutions to be implemented in order to collectively build the society of tomorrow—one that strikes a balance between digital efficiency and the protection of human rights.

The Digital State

While in some schools, enrolling a child can only be done online, homeless individuals (also known as “sans domicile fixe”) are asked to scan a QR code to access a shelter for the night, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to speak to a human being at banks or public services—are we now forced to have a smartphone practically grafted to our hands in order to (survive)live?

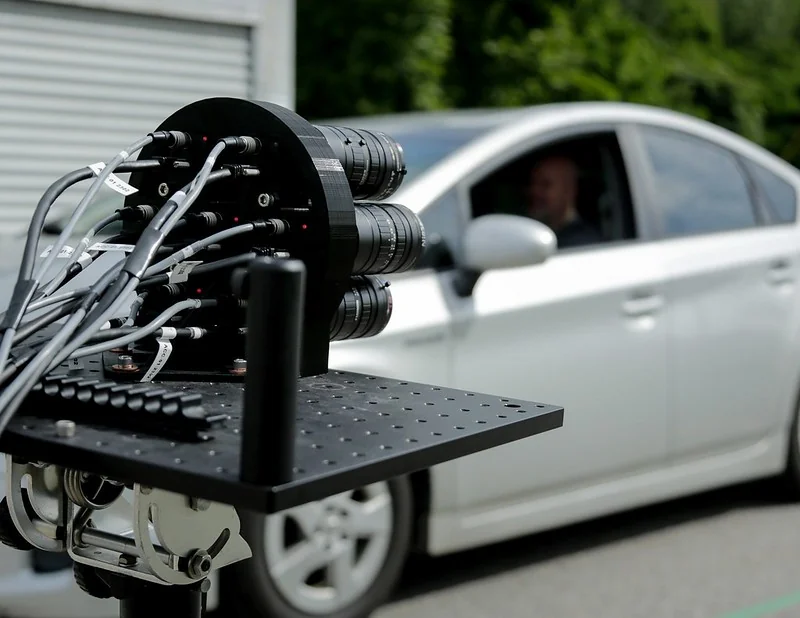

Moreover, more and more often, it is algorithms—not human State agents—that make crucial decisions affecting people’s daily lives, such as selecting migrants at Europe’s borders via a lie-detecting robot, determining who should be suspected of fraud, deciding which high school or university a child will attend, and more. Are robots, in the sense of automated processes, now the new public decision-makers?

The digitization of the State poses a threat to many fundamental rights protected by international texts and national constitutions.

These questions touch on the functioning of the digital State worldwide. This concept encompasses two aspects. On the one hand, there is what happens at the front office of an administration—the interaction between the citizen and a State agent. This agent is increasingly being replaced by a website. As a result, citizens are required to carry out administrative tasks—often complex—that were once handled by trained professionals. Citizens must now assume full responsibility for the procedures they undertake to claim their rights. This raises the question of whether “public service” is still truly a “service” provided “to” the public.

On the other hand, there is what happens behind the counter—the back office—behind the scenes of the digital State. This involves databases where we are required to provide personal information to the State from birth to death, covering all aspects of our lives (health, family, employment, housing, vehicles, leisure, etc.). This data circulates between administrations, which can be very practical—for instance, to avoid reporting a change of address multiple times, to receive a pre-filled tax return, or to obtain family allowances automatically without having to apply for them.

However, some situations are more concerning. How can we not be alarmed upon learning that, before being condemned by the European Court of Human Rights, Hungary intended to publish the names and contact details of individuals late on their tax payments on a public website? That in Belgium, a draft law proposed transferring citizens’ health data to insurance companies to adjust their premiums? That in the United States, users of the dating app “Tinder” can check the criminal records of their matches? In such cases, it is legitimate to fear that our data could be used against us.

Human Rights

The digitization of the State is not just about replacing printers… It poses a threat to many fundamental rights protected by international texts and national constitutions. Here, we focus on the Belgian Constitution.

The digital tools used by the State affect privacy and personal data (Article 22 of the Constitution). When poorly configured or malfunctioning, they can lead to discrimination and social exclusion (Articles 10 and 11 of the Constitution), just as they can prevent individuals from accessing their rights, such as unemployment benefits (Article 23 of the Constitution).

These tools can also violate the right to inclusion of persons with disabilities (Article 22ter of the Constitution) and the right to education (Article 24 of the Constitution). Finally, administrative transparency is a fundamental right in Belgium (Article 32 of the Constitution), which is also at risk when the State refuses to disclose public sector algorithms, for example.

No law requires the use of a screen to exercise one’s rights.

Should we resign ourselves and consider this an inevitable fate? Absolutely not. If digital technology were truly indispensable, it would be mandatory. However, no law requires the use of a screen to exercise one’s rights. In fact, the only tool mandated by the State—at least in Belgium—is the identity card, whose use is precisely regulated by law. Digital technology is therefore merely a tool, like a hairdryer or a bicycle. We should have the choice to use it or not, and digital tools should be adapted to society, not the other way around.

Of course, digital technology offers many advantages, and the point here is not to advocate for a return to living in the forest and communicating via parchment or smoke signals. However, we cannot ignore the fact that digitalization also comes with many drawbacks. Perhaps this is why policymakers hesitate to impose it outright. Instead, they prefer to use the “nudge” technique—giving people a gentle push to encourage its adoption.

In practice, this means encouraging people to use digital services by making life more difficult for those who do not. For example, online tax filers may be granted an additional two weeks compared to those filing on paper; long waiting lines at service counters may be accompanied by posters promoting the website; telephone services may route callers to an automated message informing them they are 19th in line and that the website is very efficient, and so on. People are presented with a fait accompli and are subtly pushed toward digital solutions.

Politicizing the Digital World

If we drove cars without following traffic rules, a crash would be inevitable sooner or later. The same applies to digitalization, which is currently expanding without sufficient safeguards, despite posing threats to human rights.

Calling for greater regulation of digital technology does not mean opposing it. On the contrary, it is an appeal for sustainable digitalization that finds its rightful place in society. If the digitalization of society continues without a clear legal framework, it will inevitably lead to disaster, causing human and material damage that the State will have to repair.

Political leaders could be held accountable and even forced to resign, as happened in the Netherlands with the collapse of the Dutch government on January 15, 2021, following the child benefits scandal, or in Australia after the Robodebt scandal. A similar issue could soon arise in France, where the algorithm used by the CAF (Caisse nationale d’allocations familiales), deemed discriminatory, is currently being challenged in court.

This is why digital technology must be politicized. Policymakers must fully engage with the issue instead of dismissing it as “too technical” or claiming that regulating these tools takes “too much time,” as is often heard. It is in everyone’s interest, as the law is a tool to be used proactively to prevent problems rather than merely react to them. In other words, establishing an appropriate legal framework for digital technology within a democratic society will ensure its harmonious development in the future while minimizing legal challenges and political liabilities.

To achieve this, each digital tool should undergo a “crash test,” similar to cars, consisting of three stages.

First, the “why”. Why should a particular tool be implemented? It is important to look beyond stereotypes such as “digital saves money” or “it is better for the environment.” These claims must be carefully evaluated and objectively substantiated on a case-by-case basis. Economically, the costs of implementation, updates, bug fixes, and cybersecurity must be considered. Environmentally, digital “dematerialization” is, in fact, highly material, given the energy-consuming and polluting resources required to operate devices.

The inner workings of the State are marked by significant opacity.

Currently, many aspects remain unclear. For example, why are school planners being digitized? Often, the response is, “everyone is doing it” or “a consultant recommended it, and we thought it was the trend.” This lack of thorough consideration can result in unforeseen consequences, such as children getting distracted by Instagram notifications instead of focusing on their digital planners, or parents struggling to manage their children’s screen time.

Second, the “how”. What tool should be implemented, and what are its advantages and disadvantages? Since a fly is not swatted with a bazooka, it is essential to select the tool best suited to the intended objective—this is the principle of proportionality. Does the tool truly achieve the desired goal? And does it avoid collateral damage that could have been prevented with a different approach? For example, COVID-19 tracking apps like “Alerte Covid,” deployed in many countries during the pandemic, faced criticism because their effectiveness in combating the virus was unproven, while they posed risks to individual freedoms, particularly privacy.

Thirdly, the law. The digital sphere constitutes what is referred to as an “interference” with fundamental rights, meaning that it infringes upon these rights, as previously mentioned. For example, transferring an individual’s new address from one ministry to another so that all administrative documents are automatically sent to the new address constitutes an interference with that person’s right to privacy.

However, in this case, such interference is not, of course, prohibited. If it were, it would prevent any use of citizens’ data, which is undesirable as it would significantly increase the administrative burden for all parties involved. Nevertheless, for such interferences with fundamental rights to be admissible in a state governed by the rule of law, there must be legislation that regulates them.

This serves as a guarantee for citizens, who have the right to be assured that any infringement on their fundamental rights meets legal requirements, particularly because such measures have been debated by parliament, are clearly outlined in a publicly accessible legal text, and, in case of dispute, can be challenged in court—especially before the Constitutional Court, which has the power to annul laws that unjustifiably infringe upon fundamental rights.

This legislative approach ensures that the deployment of digital technologies is appropriately regulated while simultaneously invigorating democracy by fostering debate and shedding light on the fundamental pillars of the society of tomorrow.

“Turnkey” Solutions

In addition to this legislative methodology, “turnkey” solutions can already be implemented.

Regarding the front office discussed earlier, it is particularly affected by the shift toward an “all-digital” and “contactless” society. In response to this trend and the challenges it creates for the population, there is increasing advocacy for the inclusion of a new fundamental right in national constitutions—the right not to use digital technology. This right to an “offline” life is an increasingly widespread demand, not only in Belgium but across Europe.

As for the back office, the inner workings of the State are marked by significant opacity. It is extremely difficult to know how our personal data is being used and how the tools that make decisions in place of humans actually function.

Therefore, there is a strong push for greater transparency regarding the algorithms used by the State to make important decisions affecting people’s daily lives. More transparency should be mandated, particularly by requiring the State to disclose an “identity card” for each algorithm, detailing its name, the name of its creators, its intended purpose, the administrations in which it is used, and more.

As these considerations demonstrate, digital technology—despite its strengths and weaknesses—offers us an opportunity to shape a balanced, responsible, and equitable democratic society. Together.