Defining Extinction: An Urgent Question

Someone approaches you and asks, “What is extinction?” The questioner has a tone of both curiosity and concern.

- Defining Extinction: An Urgent Question

- The Scientific and Philosophical Challenges of Extinction

- Rethinking Extinction: Science and Culture

- Extinction as a Challenge to Ethics and Knowledge

- Tracing the History of Extinction

- Extinction in Practice: Lessons from Species Survival and Endangerment

- What Is Extinction? A Lifelong Question

You know that extinction rates are rapidly rising in the present, and that you are not alone in wondering how much biodiverse life will persist in the coming centuries. So, answering this question comes with a sense of profound urgency and responsibility.

Recognizing that all life faces extinction might provide us with a sense of the radical solidarity towards all life.

How you answer the question “what is extinction?” speaks volumes to the most fundamental ways of making sense of what it means to be alive. But the question itself, as straightforward as it seems at first, quickly leads to a labyrinth of further questions that run into the fundamental problem: are we sure we all agree on the definition of extinction?

The Scientific and Philosophical Challenges of Extinction

Because, to answer the question, “What is extinction?” you would need to have some basic, stable, and clear definitions of life, death, and species. You would realize that these terms do not have clear consensus in the biological sciences, and that genetic material can continue to be preserved even if a species is no longer living. Certainly, extinction is a magnitude greater than individual death – it is the effacement of that species and all its relations from the realm of available biological forms. Extinction is not just the death of an animal but the end of an entire way of life.

The book examines what extinction means and what extinction does to meaning.

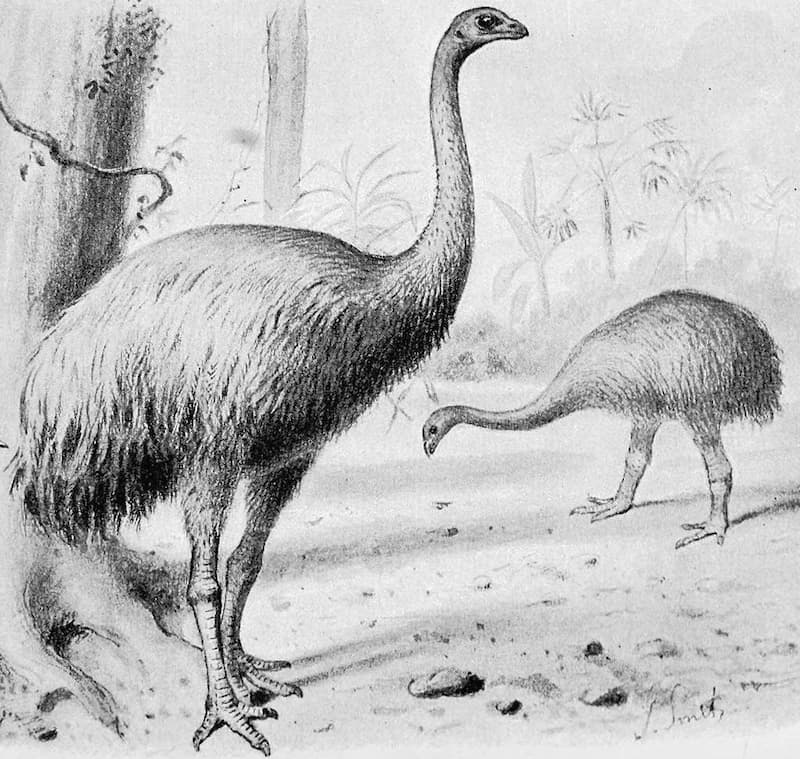

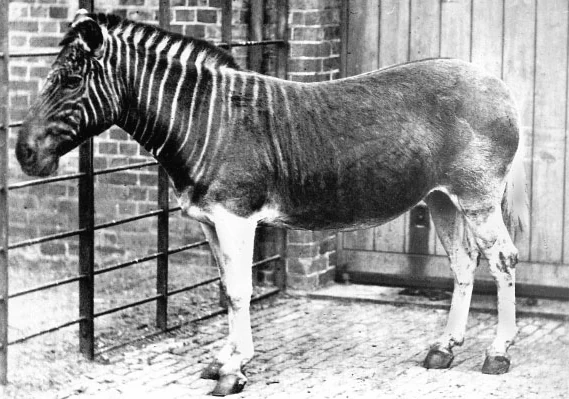

However, in the realm of genetic technologies, the assumption that “extinction is forever” is likely to be challenged in the coming decades by efforts towards the de-extinction of woolly mammoths, passenger pigeons, and thylacines.

In the humanities, the trend in recent decades has been to comprehend how life and death are not exclusive but overlap and haunt each other. To ask oneself the question of extinction induces a biological as well as a psychoanalytic reaction in ourselves – it stirs the sense of finitude in each of us. It engages what Freud called our originary traumas around death but also, and I think this is in Freud too, our originary biophilia within ourselves, towards other humans, and towards other species.

Rethinking Extinction: Science and Culture

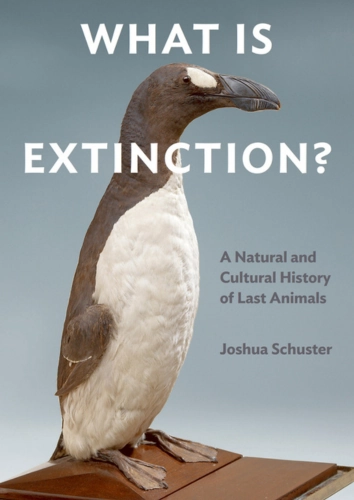

My book, What Is Extinction? A Natural and Cultural History of Last Animals, discusses different definitions and scenes of extinction from the eighteenth century up to the present. In a sentence, the book examines what extinction means and what extinction does to meaning.

Extinction is something that requires scientific study and conservation work, as well as cultural documentation, interpretation, and discussion – that’s the process of meaning making. But extinction also is something that can transform or undermine or render unintelligible all of the above. If extinction is the finiteness and existential nothingness that all life faces, how do we carry that awareness within us in everyday life?

The question “What is extinction?” cannot be answered once and for all .

I will argue that the lack of a single definition or interpretation of extinction is a good thing. First of all, we don’t need a single understanding of the meaning of extinction in order to care for endangered species.

But I also claim that one of the most important aspects of the question “What is extinction?” is that we keep asking it. If we think we have settled the debates and questions around the meaning of extinction, we put ourselves in a very dangerous position of assuming that the meaning of extinction will not change over time.

If we assert just one meaning of extinction, that definition may become the most singular focus of everything we think about and act upon. This might lead us to state that any loss of life is unacceptable, and that we must pursue biotechnologies at any cost that allow us to live forever. We might say that preventing human extinction is the most important value, and that the extinction of all other animals is warranted if it prolongs human life.

Extinction as a Challenge to Ethics and Knowledge

Michel Foucault remarked that there are a few utterances that have the power to shake the foundations of settled truths at select moments. Foucault’s example is the sentence “I lie,” a paradoxical sentence that befuddled ancient Greek philosophical attempts to codify the definition of truths.

Foucault thought the utterance “I speak” in modern times had a similar effect, for it followed from the assertion of subjectivity but also implicated the dispersion of the subject into the meanderings of language and desire.

The question “What is extinction?” elicits a trembling of everything we know in our own time. Recognizing that all life faces extinction might provide us with a sense of the radical solidarity towards all life.

But extinction events also can disrupt or even shatter ethical practices, norms of care and conservation, and established ways of responding.

Some might react to the radicality of extinction by establishing hierarchies of which life is deemed most valuable, and which life might be left to perish. In the past few centuries, we have seen the entire range of these reactions to the knowledge of species finitude.

Tracing the History of Extinction

In the book, I combine conservationist knowledge about the lastness of species with the formal analysis of literature and other media to do a “close reading” of extinction events and the changing definitions of extinction. I examine how the kinds of language, stories, styles, and conceptual terms used to document and comprehend the end of a species contribute to the meanings of extinction.

In the book’s Introduction, I provide a brief history of the scientific study of extinction, which could only emerge once one has a sense that life is not always guaranteed, and that nature has a history that changes over time. The scientific conceptualization of extinction first developed in the work of naturalists in the late 18th century and became confirmed empirically by the French naturalist Georges Cuvier who used comparative anatomy to distinguish mastodon bones from living elephants in the late 1790s. Since there was no sighting of the massive mastodon roaming North America, Cuvier insisted on the animal’s permanent demise.

It took about one generation to go from thinking species and humanity would last forever to thinking that all life on earth might have a brief past due date. At about the same time, the astronomer William Herschel conceptualized the birth and death of galaxies and applied this knowledge to the Milky Way, reasoning that our galaxy cannot last forever. That’s an incredible cognitive turnabout. It prompted William Whewell, a naturalist and contemporary of Darwin, to write in 1839: “Not only the rocks and the mountains, but the sun and the moon have the sentence ‘to end’ stamped upon their foreheads.”

Such comments divulge the realization that, in the heart of the Enlightenment, extinction showed the way toward the end of the Enlightenment. Instead of a narrative of species’ progress and improvement, extinction threw open the gates toward unknown outcomes for any form of life, while indicating that all living forms would eventually transform into ruin. The question “What is extinction?” suddenly became an inquiry that could question everything.

Extinction in Practice: Lessons from Species Survival and Endangerment

Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, which is as much a theory of the beginnings as it is of the ends of species, brought the knowledge of extinction to a much wider audience. It helped to precipitate a wave of attention to how extinctions could occur in a variety of situations and at any moment.

Extinction became then not just a question of the fossil record or some distant future event, but something that could be witnessed in the present. As people learned to be able to think about extinction as a matter of everyday concern, if they could see extinction happening in real time for a particular species, they could act to prevent it.

My book provides case studies of extinction events for plains bison, tigers, and corals, among other species. Each of these has faced mass dying events and near-extinction, only to receive intense attention to their salvation at moments of existential crisis. Yet for these species, their historical population numbers remain at very low levels today, and they continue to endure at levels of endangerment. Although these species have survived recent extinction events, their tenuous survival marks them as key barometers of what extinction means in the present.

The question “What is extinction?” cannot be answered once and for all – it has to be continually asked in multiple times and places. This question haunts us but also invigorates us. It leaves a psychic wound but also calls us to think collectively and carefully about precarious life.

What Is Extinction? A Lifelong Question

Throughout the book, I discuss how we should be able to think critically, creatively, carefully, and collectively about extinction. Thinking extinction is possibly the most important thing we might ever think about, and yet I think we must be careful about this kind of hyperbolization and extremefication of our thought. If we obsess about extinction, as if it is the only think we should think about, as people have done in key moments in the nineteenth and twentieth and twenty-first centuries, that obsession can and has been used to justify any sort of violence or abandoning the sharing of the Earth.

No doubt, in our present moment we find a multiplicity of responses to the question “what is extinction?” all around us in political rhetoric, in popular films and tv shows, and in the difficult work of biodiversity conservation. There might even be some apocalyptic fatigue with the ubiquity of cultural representations of end of the world scenarios. However, as a literary scholar, I remind my readers that the genres of elegy, apocalypse, and tragedy, that are commonly used in representations of extinction support multiple, complex, and often contradictory responses and readings.

Just having the time and imaginative capacity to consume cultural works in these genres means that the reader or viewer is not facing the dire demands of immediate self-preservation and can practice creative world imagining. Even when watching an apocalyptic show, one experiences some anti-apocalyptic aesthetics at the formal level because it requires us to savor the language and visual pleasure of art rather than living in a world without these.

Extinction might be the most meaningful thing we could talk about, or it might be the total emptying out of meaning. I think we are always going to remain between these two possibilities. I have presented here many different iterations of the question “What is extinction?” I think we will always be re-asking ourselves this question, which is a good thing, because it teaches us in continual and ongoing ways how to be ecological, that is, how to share the burdens and benefits of co-existing with biodiverse life on Earth.