Why Markets Are Never Neutral

The stock market is often presented as a neutral mechanism where prices reflect the balance between supply and demand. Yet markets are not insulated from politics.

- Why Markets Are Never Neutral

- Capitalism and the State

- Cold War Finance

- The Dollar and Global Hegemony

- Oil, Commodities, and Market Volatility

- Emerging Markets and Political Risk

- China’s Market Power

- Technology, National Security, and Investment Flows

- Sanctions and Market Fragmentation

- The Role of Sovereign Wealth Funds

- Geopolitical Crises and Investor Behavior

- Global Institutions and Regulatory Rivalries

- Climate Politics and Market Transformation

- Regional Stock Exchanges as Political Projects

- The Future: Multipolar Finance

- Conclusion: Finance as Politics by Other Means

They are shaped by state decisions, international rivalries, and geopolitical shocks that alter capital flows. To understand the stock market is to recognize that it functions within a political order—one that reflects power, security, and global competition as much as corporate performance.

Markets also serve as instruments of signaling. A sudden market downturn after a political announcement can shape how governments perceive the credibility of their own policies. Investors, too, use stock reactions to interpret political stability. Thus, beyond reflecting reality, stock markets actively participate in shaping political narratives.

Capitalism and the State

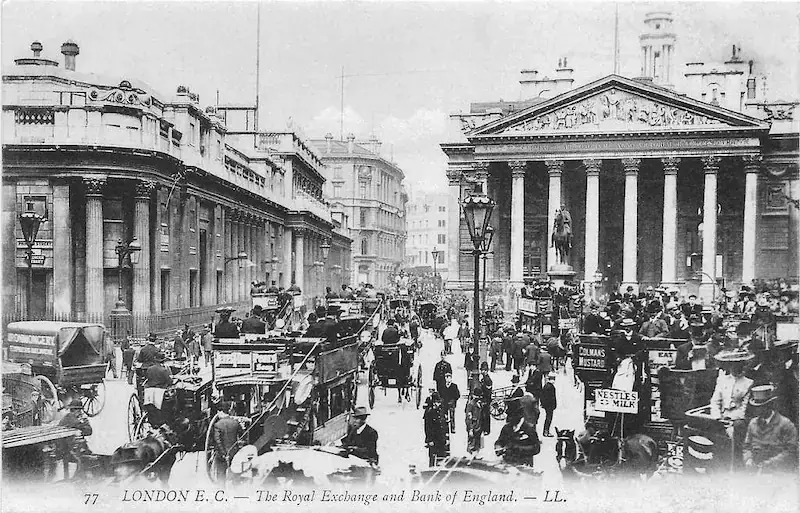

From the 19th century London Stock Exchange to Wall Street’s rise in the 20th century, the state has been inseparable from market development.

Legal frameworks, property rights, and taxation all establish the conditions for financial activity. States also determine the degree of openness to foreign capital.

In times of crisis—whether through bailouts or monetary interventions—governments become guarantors of the system.

Markets therefore depend not only on private investors but on political authority that secures trust in the rules.

This dependency also makes markets vulnerable to state overreach. Excessive intervention or arbitrary regulation undermines investor confidence, while weak enforcement creates uncertainty.

The balance between state control and market freedom is therefore central to the stability of any financial system.

Cold War Finance

The Cold War illustrates the political dimensions of capital markets. In the West, U.S. dominance in global finance was consolidated through institutions such as the IMF and World Bank, giving Wall Street unparalleled reach.

In contrast, Soviet markets were closed, reflecting ideological opposition to private ownership of capital. The division of the world into capitalist and socialist blocs reinforced the idea that finance was an extension of geopolitical strategy, with stock exchanges acting as symbols of Western economic superiority.

Additionally, financial markets became tools of propaganda. The Dow Jones or London FTSE indexes were regularly cited as evidence of capitalist dynamism, while the absence of such indicators in socialist states was portrayed as proof of stagnation. This ideological framing reinforced the geopolitical struggle far beyond military or diplomatic arenas.

The Dollar and Global Hegemony

No element demonstrates geopolitics in markets more clearly than the U.S. dollar. Its role as the global reserve currency gives American stock exchanges unmatched influence.

International investors, sovereign wealth funds, and corporations all rely on dollar-denominated assets for stability.

This hegemony amplifies Wall Street’s capacity to attract foreign capital, creating a feedback loop between U.S. geopolitical power and financial markets.

The dollar’s dominance is both an economic fact and a political weapon.

The reliance on the dollar also imposes asymmetries. Countries exposed to dollar fluctuations experience volatility in their domestic stock markets, even when their own economies are relatively stable.

This dynamic magnifies the U.S. Federal Reserve’s role as an actor with global reach, effectively granting Washington influence over capital allocation far beyond its borders.

Oil, Commodities, and Market Volatility

Resource politics remain central to market dynamics. Oil shocks in the 1970s showed how geopolitical instability could trigger global financial crises. When OPEC limited production, energy prices surged, destabilizing stock markets worldwide. Commodity markets thus connect local conflicts to global capital flows.

The intersection of energy geopolitics with stock performance continues today, with tensions in the Middle East or sanctions on Russia sending ripples through equities from London to New York to Shanghai.

Beyond oil, critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earths are now at the heart of geopolitical competition. Countries controlling these resources influence global supply chains, shaping the valuation of companies in energy, technology, and manufacturing. Market performance therefore hinges not only on corporate strategy but also on access to contested resources.

Emerging Markets and Political Risk

The rise of emerging economies has highlighted the importance of political risk in investment.

Stock markets in countries such as Brazil, India, and South Africa often show extraordinary growth potential but remain vulnerable to political instability.

Elections, corruption scandals, or sudden regulatory shifts can wipe out billions in capital.

Investors are forced to analyze not only corporate balance sheets but also the reliability of institutions, judicial systems, and the risk of authoritarian turnarounds.

Political risk analysis has thus become an industry of its own. Firms track legislative changes, electoral cycles, and governance quality to guide investors.

Yet even the most sophisticated models cannot fully anticipate sudden ruptures such as coups or mass protests. The unpredictability of politics ensures that emerging market investment is always a high-stakes endeavor.

China’s Market Power

China represents the most striking case of geopolitics shaping markets today. Since the 1990s, it has opened its stock exchanges while retaining strong state oversight. Its hybrid model—state-led capitalism combined with selective market liberalization—challenges Western assumptions.

The trade war with the United States, restrictions on technology companies, and geopolitical rivalries in Asia show that Chinese stock markets are arenas of political contestation. Investors must navigate not only economic growth but also the unpredictability of Party-led governance.

The stock market cannot be understood in isolation from geopolitics.

Moreover, China uses its financial system as an extension of foreign policy.

Initiatives like the Belt and Road project involve massive capital allocation that indirectly benefits Chinese firms listed on domestic and international exchanges.

This linkage between diplomacy and markets sets China apart from liberal economies, where corporate performance is less directly tied to state-led projects.

Technology, National Security, and Investment Flows

Technology companies are now at the center of market geopolitics. Semiconductor firms, cloud providers, and AI companies are deeply entangled in national security concerns. Restrictions on foreign investment, export controls, and protectionist policies increasingly determine which firms thrive.

The U.S. decision to limit Chinese access to advanced chips illustrates how stock valuations are tied to security calculations. Tech markets no longer move solely with consumer demand but with defense strategies and alliances.

This convergence of security and technology extends beyond U.S.-China rivalry. European debates over 5G infrastructure, restrictions on Huawei, and investments in domestic chip production reveal how security concerns now define technological markets globally. Stock prices reflect not only innovation cycles but also the outcomes of geopolitical negotiations.

Sanctions and Market Fragmentation

Economic sanctions demonstrate the geopolitical weaponization of finance. When Western nations imposed restrictions on Russian firms after the invasion of Ukraine, Russian equities were effectively cut off from global capital markets. Similar sanctions have targeted Iran and Venezuela.

These measures fragment the global market into rival zones of capital, where access to liquidity depends not on profitability but on political alignment.

The future may see further segmentation as rival blocs develop separate financial infrastructures.

The unintended consequence of sanctions is the acceleration of financial innovation outside Western systems.

Alternative payment structures, currency swaps, and regional clearing houses are being developed to bypass restrictions.

These parallel networks may gradually undermine the cohesion of global markets, pushing them toward fragmentation.

The Role of Sovereign Wealth Funds

Sovereign wealth funds, managed by states rather than private actors, represent another geopolitical dimension. Funds from the Gulf states, China, and Norway hold trillions in global equities.

Their decisions are not only about returns but also about influence. By investing strategically in infrastructure, technology, and energy, these funds extend their states’ geopolitical leverage. The line between financial investment and foreign policy tool becomes increasingly blurred.

Explore Books Written by Our Contributors

The size of these funds also allows them to stabilize domestic economies while projecting influence abroad. For example, during oil price downturns, Gulf sovereign funds cushion local fiscal budgets by reallocating assets, while simultaneously acquiring strategic stakes in Western firms. This dual role strengthens their geopolitical weight.

Geopolitical Crises and Investor Behavior

Markets also reveal how investors react to uncertainty. Wars, terrorism, pandemics, and diplomatic tensions generate volatility. Flight-to-safety behavior—where investors rush into U.S. Treasuries or gold—illustrates how geopolitical crises create predictable patterns in stock markets.

Climate politics is inseparable from market forecasts.

Yet crises also generate winners: defense contractors, energy producers, or pharmaceutical firms often benefit from upheaval. Understanding the geopolitics of markets requires analyzing not only macro trends but also sectoral realignments in times of conflict.

The COVID-19 pandemic provided a vivid example of how crises can redistribute market fortunes. While tourism and aviation collapsed, technology and health-related stocks surged. These dynamics underscore that crises are not merely destructive—they restructure the hierarchy of winners and losers across global markets.

Global Institutions and Regulatory Rivalries

International institutions attempt to stabilize markets but also reflect geopolitical struggles. The Basel Accords on banking, the role of the IMF in crisis management, and the World Trade Organization’s impact on capital flows all show how governance structures shape equities.

Meanwhile, regulatory competition—between U.S. standards, EU directives, and Chinese rules—forces multinational corporations to adapt to conflicting frameworks. Markets become sites where legal pluralism reflects geopolitical rivalry.

This contest also extends to financial technologies. Competing frameworks for digital assets, crypto regulation, and central bank digital currencies reveal how institutions are shaping the next stage of financial globalization. The regulatory race has direct implications for stock valuations in fintech and banking sectors.

Climate Politics and Market Transformation

The politics of climate change increasingly influence market dynamics. Green finance, carbon trading, and ESG (environmental, social, governance) frameworks push firms to adapt to new regulatory environments. State commitments to decarbonization affect valuations in energy, manufacturing, and transport.

Yet geopolitics complicates this transition: countries rich in fossil fuels resist rapid change, while others see green technology as a new frontier of global competition. Climate politics is thus inseparable from market forecasts.

At the same time, climate-related disasters pose systemic risks. Hurricanes, droughts, and wildfires disrupt supply chains, destroy infrastructure, and directly affect corporate profitability. Markets therefore integrate not only policy expectations but also the physical consequences of climate change.

Regional Stock Exchanges as Political Projects

Stock exchanges are not only financial institutions but also symbols of national prestige. Efforts by countries like Saudi Arabia to expand their exchanges are tied to ambitions of geopolitical visibility.

Regional hubs—Dubai, Singapore, Johannesburg—compete to become gateways for capital, linking finance to diplomatic strategy. The competition among exchanges shows how financial centers themselves become instruments of soft power, reinforcing states’ geopolitical positions.

These exchanges also act as vehicles for economic diversification. For example, Gulf states use them to reduce reliance on hydrocarbons, while African nations leverage them to attract international capital. Their success or failure has direct implications for states’ broader geopolitical standing.

The Future: Multipolar Finance

Looking ahead, the stock market faces a multipolar future. While Wall Street remains dominant, the rise of Asian and Middle Eastern financial hubs suggests a diffusion of capital influence. Rival digital currencies, alternative payment systems, and regional alliances may reduce dependence on U.S. financial infrastructures. Yet this will not lead to a single alternative system. Instead, markets will operate across fragmented blocs, reflecting a world where power is distributed across multiple geopolitical poles.

A multipolar system also implies greater uncertainty. With no single authority capable of imposing order, crises may generate more severe financial instability. The lack of coordination among rival blocs could amplify volatility, making geopolitical literacy indispensable for investors and policymakers alike.

Conclusion: Finance as Politics by Other Means

The stock market cannot be understood in isolation from geopolitics. Capital flows reflect not only investor expectations but also the global distribution of power. Markets embody the tensions between states, ideologies, and strategic rivalries.

To study the geopolitics of the stock market is to recognize that finance is not just about profit—it is about who governs the rules of the global economy. As the 21st century unfolds, the line between markets and politics will only grow thinner.

Equally important, stock markets serve as early warning systems of political fragility. Sharp capital outflows, declining indexes, or sudden surges can foreshadow deeper geopolitical transformations. For analysts and citizens alike, understanding these signals is essential to grasping the future trajectory of world order.