Nearly 12.5 million enslaved Africans were transported to the Americas during the era of the Atlantic slave trade. Half of these African captives were forced into slave ships departing from West Central Africa.

Likewise, of the approximately 10.7 million enslaved men, women, and children who disembarked alive in the New World, approximately five million enslaved persons came ashore in Brazil. Meanwhile, about 300,000 enslaved Africans landed in the present-day United States.

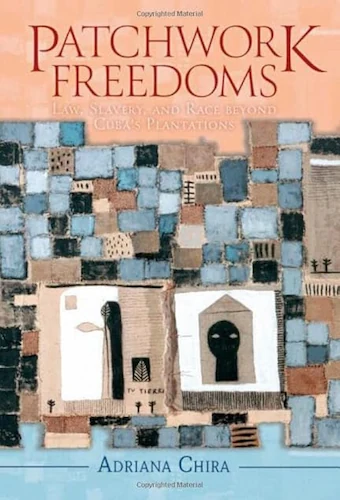

I argue that the lived experiences of enslaved women are crucial to understanding slavery and its aftermath in the Americas.

These numbers reveal the centrality of Brazil and West Central Africa to understanding the history of the Atlantic slave trade. But Brazil’s importance goes beyond these numbers. The country was also the last nation in the Western Hemisphere to abolish slavery, in 1888.

Today, the inheritance of this long slave-trading past is visible in Brazil as the country has the second largest population of African descent in the world, after Nigeria.

In contrast with other regions of the Americas, Brazil was closer to West Africa and West Central Africa. Atlantic sea currents and winds also favored the voyages between Brazil and Atlantic Africa. Therefore, the rise of the Atlantic slave trade propelled an intensive bilateral trade between Brazil and West Central Africa (especially the region of present-day Angola) and the Bight of Benin (the region encompassing Togo, the Republic of Benin, and Nigeria), giving birth to the South Atlantic system.

This configuration allowed Portuguese and Brazilian traders to transport approximately six million enslaved Africans to Brazil. Most of these men, women, and children left Africa from Luanda, Ouidah, and Benguela.

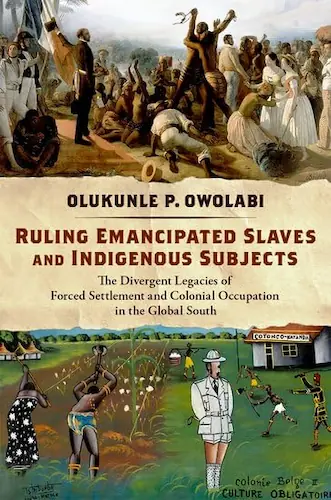

Given these long-established facts, Humans in Shackles: An Atlantic History of Slavery retells the long history of slavery by centering on Brazil and West Central Africa, as well as on the crucial role of enslaved women.

Brazil and Latin America Matter

My book seeks to redress the distortions and imbalances in existing general histories of slavery that have largely focused on the British colonies in the Caribbean and North America, and later the United States.

Take the example of the year 1619. Although 1619 has been a site of memory for African Americans for many decades, the date has no significance outside the United States. Therefore, I argue that to fully understand this landmark year it is central to consider the long-lasting impact of the Portuguese and Brazilian slave trades. Why?

The answer is simple: the twenty enslaved Africans brought to Virginia via the Caribbean in 1619 were seized by the English from the Portuguese slave ship São João Bautista, which was sailing from Luanda to the port of Veracruz in today’s Mexico.

Most importantly, in the entire century that preceded the year 1619, at least 370,000 enslaved Africans had already landed in the Americas. This figure is more than the estimated number of enslaved Africans brought from Africa to the United States during the entire period of the Atlantic slave trade.

By arguing that this emphasis on the British slave trade and the North Atlantic system has blurred the real dimensions of slavery and the slave trade in the Americas, Humans in Shackles puts Brazil, the West Indies, the Spanish-speaking Americas, and North America side by side.

I place Brazil and the South Atlantic system at the center of the narrative, highlighting the role of African societies during the era of the Atlantic slave trade and slavery. My main claim is that Brazil, the Luso-Brazilian slave trade, and the African contexts are central to fully understanding the long and painful history of the Atlantic slave trade and slavery, as many realities that existed in Atlantic African societies, especially in the coastal areas were mirrored in the port cities of the Americas.

As I conceived, researched, and wrote the book, my aim was also to respond to the many misconceptions about slavery in the Americas. For example, many people, including some scholars and college students, still believe that slavery in Latin America, including Brazil, was a benign institution. My book challenges this widespread and misleading idea that views slavery in Latin America and Brazil as milder in comparison with the harsh conditions of bondage in the British colonies of North America and the Caribbean. Instead, I insist slavery in Latin America was equally as violent, if not more so.

A Human History Centering Enslaved Women

Humans in Shackles is also in dialogue with works by several historians, including Marcus Rediker and Jennifer Morgan, who have explicitly criticized the excessive focus on demographic and economic dimensions of slavery. Along with other historians, they called us to write human histories of slavery and the Atlantic slave trade that emphasize the lived experience of enslaved men and women. Based on these foundations, Humans in Shackles explores the social, cultural, and religious dimensions of the lives of bondspeople.

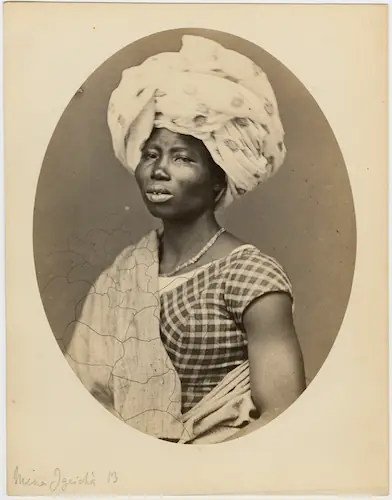

To do so, throughout the seventeen chapters of the book I illuminate the crucial role of enslaved women in the Americas, even though bondswomen were numerically inferior to men in slave societies such as Brazil. By emphasizing the importance of memory, I argue that the lived experiences of enslaved women are crucial to understanding slavery and its aftermath in the Americas. Thus, several chapters focus on enslaved African women and their descendants, by exploring their various social, cultural, and economic roles during the period of Atlantic slavery.

Humans in Shackles draws on twenty years of research in archives, libraries, museum collections, and historical sites in cities across the United States, Canada, Brazil, Portugal, France, Britain, the Netherlands, and the Republic of Benin.

I explore sources such as slave ship logs, slave ship captains’ journals, chronicles, slave narratives, wills, post-mortem inventories, correspondences, travel accounts, newspaper articles, criminal records, legislation, runaway slave ads, ads of sale, oral histories and traditions in English, Portuguese, Spanish, and French.

As a scholar trained with a PhD in history and a PhD in art history, I also incorporate visual and material culture in my research, including paintings, engravings, watercolors, photographs, and artifacts.

Although most primary sources illuminating the history of slavery were mediated or produced by male historical actors, I try to highlight the stories of enslaved persons to show them as protagonists and not as mere supporting figures.

I show that despite having been relegated to the background of historical narratives, enslaved women were central pillars of Atlantic slavery, even if they were outnumbered by men among enslaved Africans transported to the Americas by a ratio of two to one. Enslaved women were central to slave societies and societies where slavery existed in the Americas as they gave birth to children who were born in slavery.

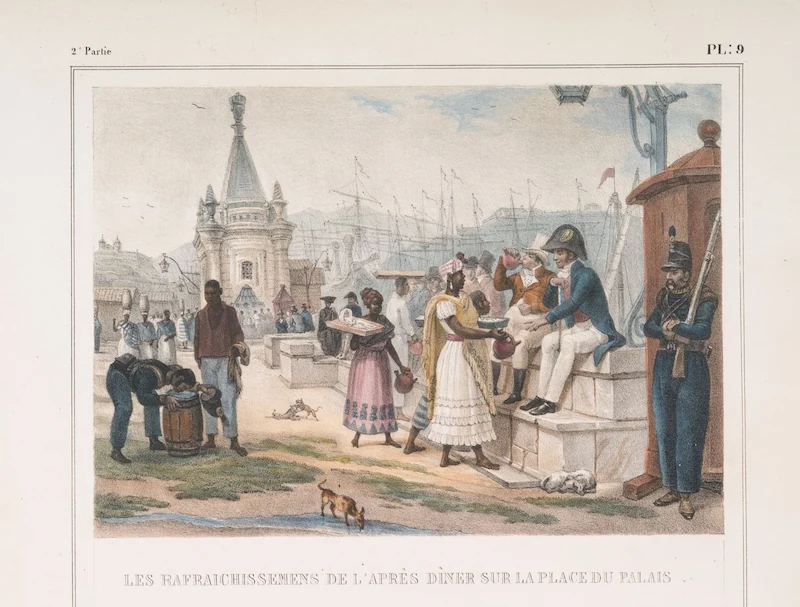

Les rafraîchissements de l’après-dîner sur la place du palais (After-Dinner Refreshments on the Palace Square) in Jean-Baptiste Debret, Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil, Paris: Firmin Didot Frères, 1834–1839; second part, plate 9.

Bondswomen nursed the offspring of their owners. They took care of the children of other bondswomen. On the cotton plantations of Louisiana in the United States or on the coffee plantations of São Paulo in Brazil, enslaved women performed strenuous physical work. In cities of Latin America and the Caribbean, such as Lima, Rio de Janeiro, Mexico City, and Havana, enslaved African women and their descendants toiled all day in the streets selling food, often to be able to buy the freedom of their loved ones.

The rise of the cotton industry and the invention of the cotton gin marked a new expansion of slavery in the United States.

Enslaved women worked by cooking, cleaning, sewing, seeding, and harvesting. Slave owners sexually abused enslaved women, for whom refusing their advances could result in severe punishment.

Even then, enslaved women resisted by running away alone or in groups, and even carrying their children.

They fought back by killing their owners. They resisted and survived by accumulating meager sums that over the years allowed them to purchase their freedom.

Because of its large annual imports of African-born individuals, Brazil became a crucial spot where African cultures and religions survived, evolved, adapted, mixed, and more than anything else developed a dialogue with European and Native American cultures.

Although this process carried features similar to other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean, these cross-cultural exchanges often contrasted with the British colonies of North America and what later became the United States, where the imports of enslaved Africans were more than ten times smaller than in Brazil. Still, across the Americas, we can see the rise of African-based religions such as Candomblé and Santería, the worship of Black saints, and the emergence of festivals, dances, martial arts, and foodways drawing on the traditions they brought from the African continent.

To juxtapose the South Atlantic and the North Atlantic systems, I also underline that a significant proportion of African-born bondspeople were introduced into mainland North America through the intra-American slave trade, especially through the Caribbean. I highlight the dramatic growth of the US enslaved population between 1790 and the years preceding the Civil War.

The rise of the cotton industry and the invention of the cotton gin marked a new expansion of slavery in the United States. Meanwhile, the Saint-Domingue Revolution and its aftermath also contributed to the expansion of Cuba’s and Brazil’s sugar and coffee industries. Designated as “second slavery,” this new phase propelled a new development of the institution of slavery entangled with the rise of industrial capitalism.

Just as any other work of synthesis, this book is not an encyclopedia and, obviously, remains incomplete. Not all regions, themes, and periods receive the same attention, as I had to weave together cases that allowed me to explore the book’s central themes. My choices were guided by the availability of primary and secondary sources and by my own experience and interests in researching and teaching the history of slavery, the Atlantic slave trade, and African diaspora history.

While providing a comparative and transnational perspective of the history of these human atrocities, I also follow the approach of African diaspora history, which treats the history of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the Americas as the continuation of their experiences on the African continent. My point of departure to write an Atlantic history of slavery was the idea that, despite specific national and regional contexts and the trends that oriented the Atlantic slave trade from disparate regions in West Africa and West Central Africa to each part of the Americas, there were also many similarities between the institutions of slavery all over the Americas.

As I conducted research and wrote this book, these similarities became even clearer. Therefore, I put Chica da Silva in Brazil side by side with Elizabeth Hemmings, Sally Hemmings, and Julia Chin in the United States. I also wove together the Tacky’s Revolt in Jamaica, the Nat Turner’s Rebellion, and the Malê Revolt in the same chapter.

In all the regions of the Americas where slavery existed to a greater or lesser extent, whereas enslaved Africans and their descendants left deep imprints in urban and rural landscapes, shaping American cultures, white settlers created mechanisms to prevent the emancipation of enslaved populations and to control freed populations even after the end of slavery.

Although the long history associated with slavery and the importance of populations of African descent has been acknowledged in some parts of the Americas more than in others, full recognition of the harms caused by slavery and the Atlantic slave trade remains unachieved, which is why the past of Atlantic slavery remains such an important topic of debate in the public sphere. And this is also why my work, shaped by the approach of memory studies, gives me a unique point of view when writing an Atlantic history of these human atrocities.

Ultimately, the echoes of this past have remained alive in the present. And because this past still matters, Humans in Shackles proposes to cross this memory’s foggy zone intoxicated by the harms of the past, to attempt to get a more nuanced and better understanding of the long era in which humans racialized as Black were placed in shackles to construct the hemisphere we know today as the Americas.