I was fortunate to be introduced to socio-political concepts at the age of 16 while studying a subject called Political Thought, available through the International Baccalaureate curriculum in the 1990s. I had left Northern Finland to complete secondary schooling with the help of a scholarship at the United World College of the Atlantic in Wales.

In many ways, this entailed emerging from the wilderness of forests, rivers, and reindeer into the realm of ideas. Perhaps this juxtaposition is the reason why I have always considered it important to link concepts, contexts and practices, and became interested in social policy.

Social policy sometimes is considered the poor cousin of ‘proper’ disciplines like sociology, philosophy, politics and law. Much of the literature on social policy is applied, and it is easy to overlook its connections to the grand ideas grounded in the abovementioned fields. But these connections matter more than ever, given the urgency of understanding and developing concepts that underpin the (re)distribution of resources in complex and fragmented societies.

Concepts Are Powerful

Social policy entails a large stock of workaday concepts that are necessary for making sense of policies and debates about them. It is essential to understand that universal benefits and services are associated with more inclusive societies than those that ensue from means-testing and reliance on family for meeting care needs.

TikTok tells us that China is democratic, and Donald Trump claims that his opponents are communists.

It is important to appreciate that cutting expenditure on childhood services resonates across the life course. These are just some of the key concepts that enable us to compare the social realities and outcomes that result from different social policies.

Contrary to the tired and entirely incorrect trope of the death of welfare states, social policy is very much a growth industry. Massive improvements in human welfare and wellbeing have been achieved through social policies. We can take solace from the progress that is evident in the implementation of many social innovations over time such as free primary education and expansion of entitlements to income supports in developing welfare states.

But the solutions to the challenge of redistributing resources have evolved over time, and new ones are called for as the focus moves from conventional social risks to addressing multiple social, political and environmental crises in turbulent times.

Concepts Can Co-Exist

Everyday lives are shaped by social policies that reflect varying conceptions of freedom, equality and (social) justice, as manifest in the structure of benefits and services and in the purpose of different welfare states. These grand concepts are not mutually exclusive, as is claimed by those who are in the business of promulgating simplistic ways of framing ideas.

Freedom, in particular, is subjected to this form of abuse: the claim that it is in fundamental opposition to all forms of equality is a damaging falsehood. Freedom and equality can co-exist peacefully and productively in the form of social policies that address structural inequalities and enable (free) people to participate in society. They can be combined in a mutually reinforcing manner through social policies that enhance human capital and increase the scope of choices available in employment, family life, and education.

Freedom and equality can co-exist peacefully and productively in the form of social policies that address structural inequalities.

Even freedom of expression and justice as recognition (of inequalities) can be reconciled, if we know the concepts that define where free speech crosses over into denial of dignity and rights of others. We need to cultivate more discourses where the connections and alignments between concepts are highlighted, instead of pitting them against each other as if they were mortal enemies.

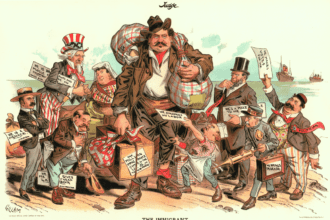

Concepts Are Vulnerable

Even a casual observer of politics is aware of the misuse of concepts in the realm of political debates and policymaking, not to mention social media. TikTok tells us that China is democratic, and Donald Trump claims that his opponents are communists.

Justice can no longer be thought of as something that pertains to humans alone.

Given that many young people rely on social media as their primary source of news, this calls for clear and emphatic correction of such misconceptions by their educators (and my book is intended to help in that process).

Understanding the origins and meaning of concepts should not be the preserve of the highly educated elites alone. Memory and understanding of core ideas that underpin civilizations can be lost and corrupted in one generation. This does not mean that concepts like freedom, equality and justice are set in stone.

Concepts Must Evolve

Perhaps the hardest reality that contemporary social policy scholars and advocates must face pertains to the deep connections between social protection, capitalism, (over)consumption, and environmental degradation.

The social policy concepts that have helped to banish extreme exploitation of labour and dire poverty in the event of sickness or retirement in many countries, are also underpinning the modes of production and consumption that are now threatening the sustainability of the environments that we all depend on.

New concepts are needed that animate the connections between policies in the here and now, and human and non-human life in future.

Much of social policy has centred around individual rights, defined and implemented within welfare states. Given that our era is widely seen as a precipice or lynchpin where decisions taken or not taken become extremely far-reaching and perhaps even irreversible, it is surprising how little of the discourse revolves around responsibilities. Or rather, the idea of responsibility has remained stagnant, with a focus on personal and family survival and success, at time when the survival of entire ecosystems is at stake.

Freedom, equality, and justice will be with us for a long time yet, but we must make new connections between them, and develop new concepts fit for the challenges that face us today. Justice can no longer be thought of as something that pertains to humans alone. The field of environmental justice has progressed towards conceptualising the non-human underpinnings of the very possibility of thinking about justice. Social policy scholars are increasingly hard-pressed to omit from their conceptualisation of justice and solidarity the non-human entities that support human welfare but are now threatened.

Future Concepts

Instead of redistributing resources within societies over short time horizons, we need to turn to redistributing across much wider timespans and entities comprising the environments that our wellbeing ultimately relies on. The human ability to see ourselves and our time as part of an extensive continuum of time and resources is currently underdeveloped; new concepts are needed that animate the connections between policies in the here and now, and human and non-human life in future. We should start thinking about our legacies not just in terms of material ones passed down family generations but also as enablers or obstacles to viability of future human and non-human life.

Twentieth-century welfare states delivered on massive improvements of human welfare and boosted economic growth with short time lags between political promises and implementation of social policies. Today, we need concepts that point to capabilities and communities far beyond our immediate surroundings and time; concepts will be key to widening our temporal and spatial horizons. The idea of long-term or deep future requires much more attention; social theorists and decisionmakers ought to consider the freedoms and rights of future people and natural entities much more seriously than has been the case to date.

Exhorting individual moral choices features in primitive interventions (such as workhouses) and in punitive aspects of means-testing, but such exhortations are not at the heart of social policy which I define as systems for redistributing resources that meet needs. The world is full of good people trying to do the right thing (or just to get by), which on its own is not going to solve the climate crisis or any other major policy challenge of this century. Systems by themselves are empty machines that soon malfunction; we need ideas to power them.

If Concepts Can’t Save Us, Nothing Will

My native Finland sets great stock on technology and engineering as a solution to societal challenges, an approach works in many cases (for example, public transport is extensive, frequent and easy to use in cities). Yet solving the crises of our time requires more than technology. Technology can help to control some forms of adverse human impact on the biosphere, but it also fuels the forms of consumption that are the cause of those impacts.

My book does not offer ready solutions to the challenges of eco-social policymaking, but it does emphasize the centrality of ideas and concepts in the process of seeking solutions. Profound change begins with a novel conception of who we are and what we want to accomplish. Too little faith is put in concepts while excessive hope is invested in various technology-driven fixes in policies as diverse as elder care, education and employment.

The study and development of socio-political concepts deserves more time and resources because therein lies the only possible exit from the multiple crises of today. Social policies can be used to implement changes, alongside or after fundamental concepts have been (re)developed in search of what we want future societies and environments to look like. Among other things, this might call for returning to contemplate the forests, rivers, animals, and plants that sustain human welfare and formed the backdrop of my early life, followed by an excursion into the realm of new ideas.

The views and opinions expressed are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority bears responsibility for them.