Rise to power

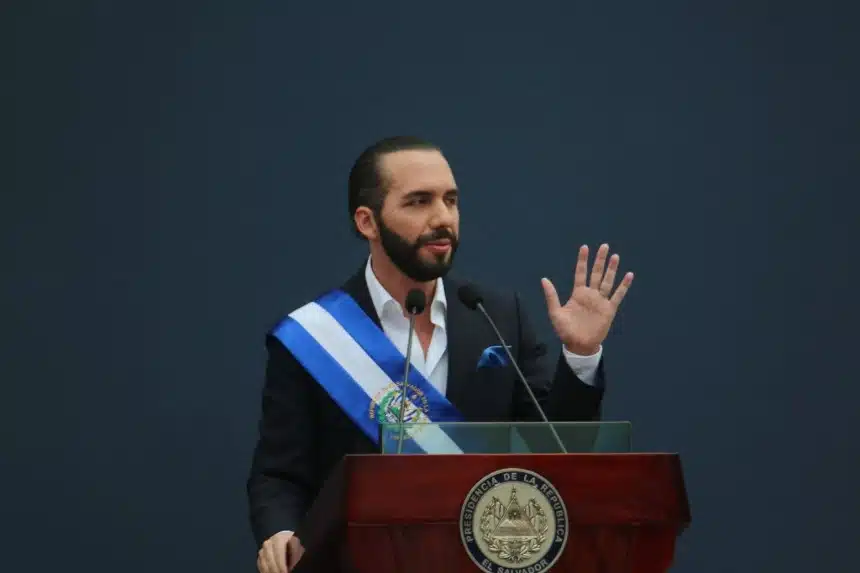

Nayib Armando Bukele Ortez, the former mayor of San Salvador and a leader boasting one of the highest domestic approval ratings globally, became the first president to emerge from outside the traditional two-party system since the Salvadoran Civil War. His own creation, the New Ideas party, aligns itself with the Third Way ideology, seeking a balance between economic liberalism and social policies.

Often likened to Trump for his populist anti-establishment rhetoric and frequent criticism of the media, Bukele has garnered significant civilian support through his effective restoration of security, despite numerous actions that undermine democratic principles.

Bukele’s security strategy in El Salvador is inspiring neighboring countries to adopt similar approaches.

This young leader’s adept use of technology, demonstrated by his push to recognize bitcoin as legal tender, along with his proficient use of social media, has won him the moniker “Coolest Dictator in the World”—a title he embraces on X (formerly known as Twitter) to ironically deflect criticism.

Assuming office in 2019, Bukele vowed to bring stability and safety to a nation plagued by the highest murder rates in the world, a consequence of rampant gang violence. Early in his tenure, he unveiled the “Territorial Control Plan,” aimed at bolstering police presence and enhancing the capabilities of the national civil police and armed forces.

State of Emergency and Mass Incarceration

On March 26, 2022, a violent confrontation between the country’s two largest gangs resulted in the murder of 62 individuals in a single day. In response, the Legislative Assembly, dominated by Bukele’s party, activated Article 29 of the Constitution the following day, declaring a state of emergency that permitted the suspension of specific civil liberties for national security reasons. This state of emergency has been renewed 24 times to date, each extension lasting the maximum allowed duration of 30 days, with officials asserting the policy will persist until gang presence is eradicated from the streets.

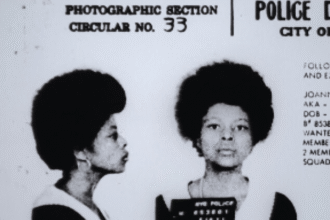

Numerous young individuals have reported being detained without just cause or evidence of gang affiliation.

The comprehensive deployment and arming of military forces have spearheaded a vigorous campaign leading to widespread incarceration. Notably, the government has inaugurated the Terrorism Confinement Center in Tecoluca, now among the world’s largest prisons, featuring cells for punishment and work facilities, and designed to house as many as 40,000 inmates.

Multiple reports and video evidence circulating on social media highlight severe human rights violations and dire living conditions within these detention facilities.

Bukele has publicly issued threats to withhold food from prisoners should any gang members at large engage in criminal activity. Furthermore, numerous young individuals have reported being detained without just cause or evidence of gang affiliation, based solely on the presence of tattoos or residence in high-risk areas.

This suspension of the right to be informed about the reasons for their arrest has led to widespread instances of arbitrary detention. Adding to the controversy, in 2022, the Deputy Minister of Justice declared plans to demolish the grave markers of deceased gang members as a strategy to dismantle the idolization of criminal figures.

Record-Breaking Rates

The aggressive tactics employed by the government have dramatically curtailed violence, as evidenced by the detention of 75,000 individuals suspected of gang connections, which precipitated a remarkable decline in the country’s homicide rates. From leading the world in 2018 with a rate of 52 homicides per 100,000 people — and an even more alarming figure of 103 in 2015 — the rate plummeted to 2.4 per 100,000 by the end of 2023. This rate not only positions El Salvador lower than nearly every other Latin American country but also below the worldwide average.

Consequently, 2023 saw El Salvador attain the highest incarceration rate globally. Despite the implications of such a statistic, the populace has largely endorsed these stringent measures, expressing a sense of safety unprecedented in recent memory. This widespread public approval has buoyed President Bukele’s approval ratings, consistently hovering around 90% during his term.

The success of Bukele’s security strategy has resonated beyond El Salvador’s borders, prompting neighboring countries facing similar challenges to adopt comparable approaches. For instance, the Castro administration in Honduras declared a state of emergency towards the end of 2022 in an effort to curb violence and criminality, albeit without achieving the significant impact seen in El Salvador. Similarly, in early 2024, the newly inaugurated President Noboa of another regional nation introduced measures such as suspending the right to assembly, infringing on the sanctity of private homes, and enforcing a nationwide curfew, mirroring Salvadoran policies.

Controversial Anti-Democratic Actions

The administration has been embroiled in numerous controversies, not least among them accusations of covert negotiations with MS-13, a notorious gang in the region. Furthermore, the state of emergency has granted the executive branch the ability to bypass the Law of Acquisitions and Procurement, managing funds without the usual oversight.

The international community’s concerns over signs of increasing authoritarianism in El Salvador are well-founded.

During the constitutional crisis known as “9F” (February 9th) in 2020, President Bukele escalated tensions by deploying 40 army personnel to the Legislative Assembly amid growing political turmoil. This forceful action aimed at securing approval for a loan to finance the Territorial Control Plan was widely criticized as an attempted coup.

In a move that further strained democratic norms, the New Ideas Party-dominated Assembly dismissed the Attorney General and five Supreme Court Justices who were critical of Bukele’s methods. Subsequently, the legislative body underwent a significant change with the reduction of its seats from 84 to 60, thereby consolidating more power within the ruling party. This pattern of diminishing the separation of powers is indicative of a broader trend observed in other nations with populist regimes, where leaders have sought to strengthen their hold on power, mirroring developments in countries like Mexico and Israel.

Questionable Constitutional Re-election

In a controversial move, the newly appointed Supreme Court in September 2021 reversed a 2014 ruling that mandated a ten-year interval between presidential terms, thereby enabling immediate re-election. This decision was met with criticism from legal scholars who argued it contravened multiple constitutional clauses, including Article 152, which prohibits anyone from serving as president if they have occupied the office within the six months preceding the new term. To align with this stipulation, Bukele took a temporary leave from the presidency, from December 1, 2023, to May 31, 2024, appointing Claudia Juana Rodríguez de Guevara as the interim president until his subsequent term commenced.

On February 4, 2024, Bukele was re-elected president with 83% of the vote, as announced by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal. The runner-up, Manuel Flores, garnered less than 7% of the votes. Bukele’s party, New Ideas, secured 58 of the 60 seats in the Legislative Assembly, ensuring an overwhelming majority.

Addressing a jubilant crowd from the presidential balcony, Bukele proclaimed his victory as a historic moment for a single party to govern in what he termed a “purely democratic system.” He critiqued international bodies like the UN and the OAS, accusing them of meddling in Salvadoran internal affairs, contrary to the populace’s clear preference expressed through the ballot. Bukele also rebuked countries such as Spain, accusing them of embodying ‘colonialism’ and ‘elitism’ while positioning themselves as democratic exemplars for El Salvador.

He emphasized El Salvador’s transformation from one of the most dangerous countries globally to the safest in the Western Hemisphere, challenging the narrative that Salvadorans are oppressed or adverse to the state of emergency. Instead, he portrayed El Salvador as a nation resolute in its governance choices.

The Complex Trade-off

In the delicate balance between civil liberties and public safety, the people of El Salvador have cast their vote, opting for security at the cost of democratic principles and personal freedoms. President Bukele has argued that, under the principle of national sovereignty, Salvadorans have the right to choose their own form of governance, particularly given their history of endemic violence that remains largely incomprehensible to outsiders.

However, history has shown that dictatorships often emerge from a foundation of widespread public support, only to devolve into regimes that suppress the very citizens they initially vowed to safeguard. The principles of human rights and the separation of powers stand as fundamental tenets of any democracy that claims such a title. These principles cannot be compromised or selectively applied without undermining the very fabric of democratic governance. The international community’s concerns over signs of increasing authoritarianism in El Salvador are well-founded, particularly in light of similar trends in neighboring countries.

This cautionary stance serves as a reminder that the allure of immediate safety and stability can lead to the erosion of the democratic values and individual freedoms that form the cornerstone of a truly free society.